1. A problem

Because stories are the One Tool to Rule Them All, the story of the whole world is the backbone of an Egan education — see the earlier pattern of Big History°. It connects everything, and helps give everything its flavor.

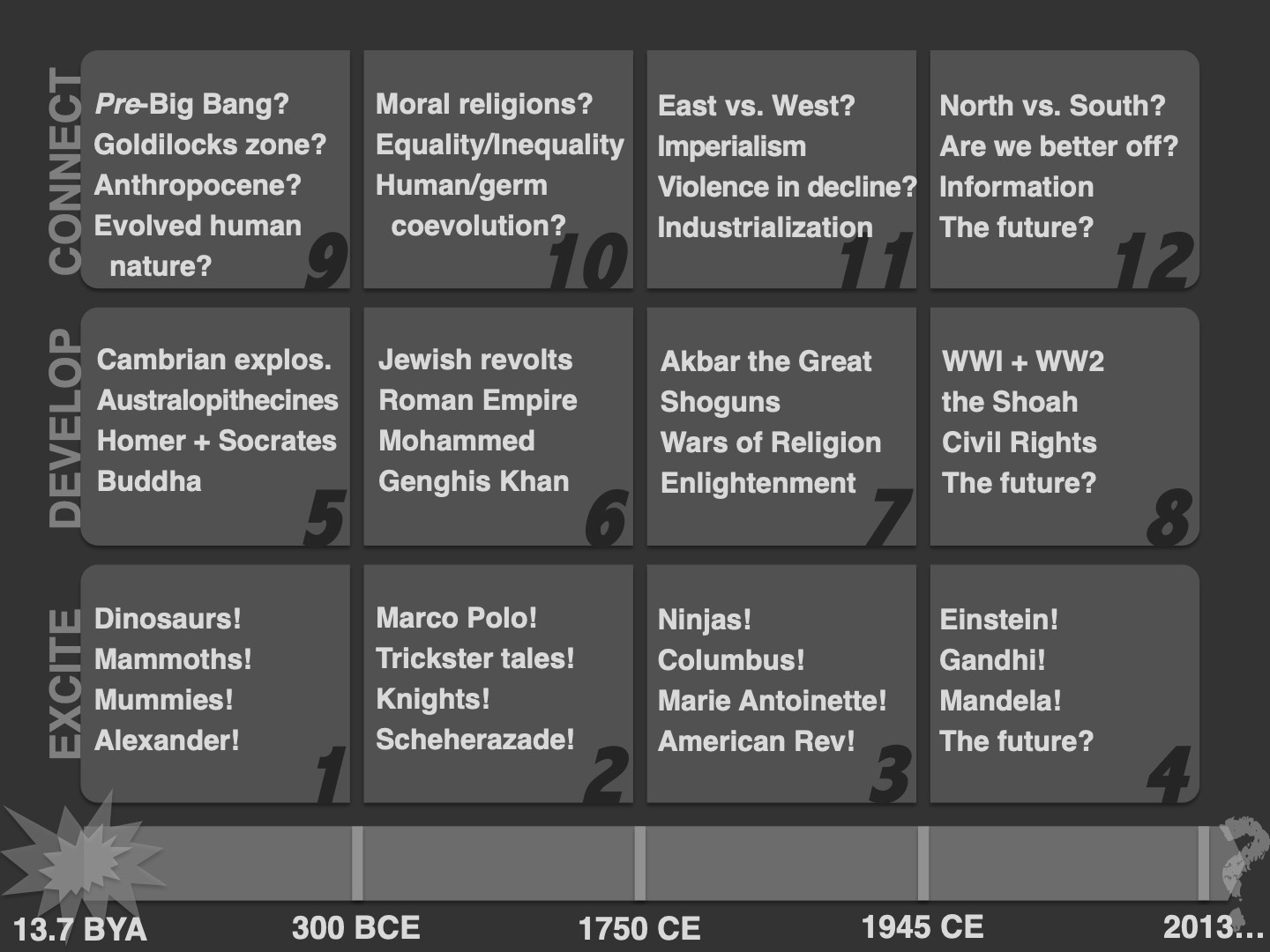

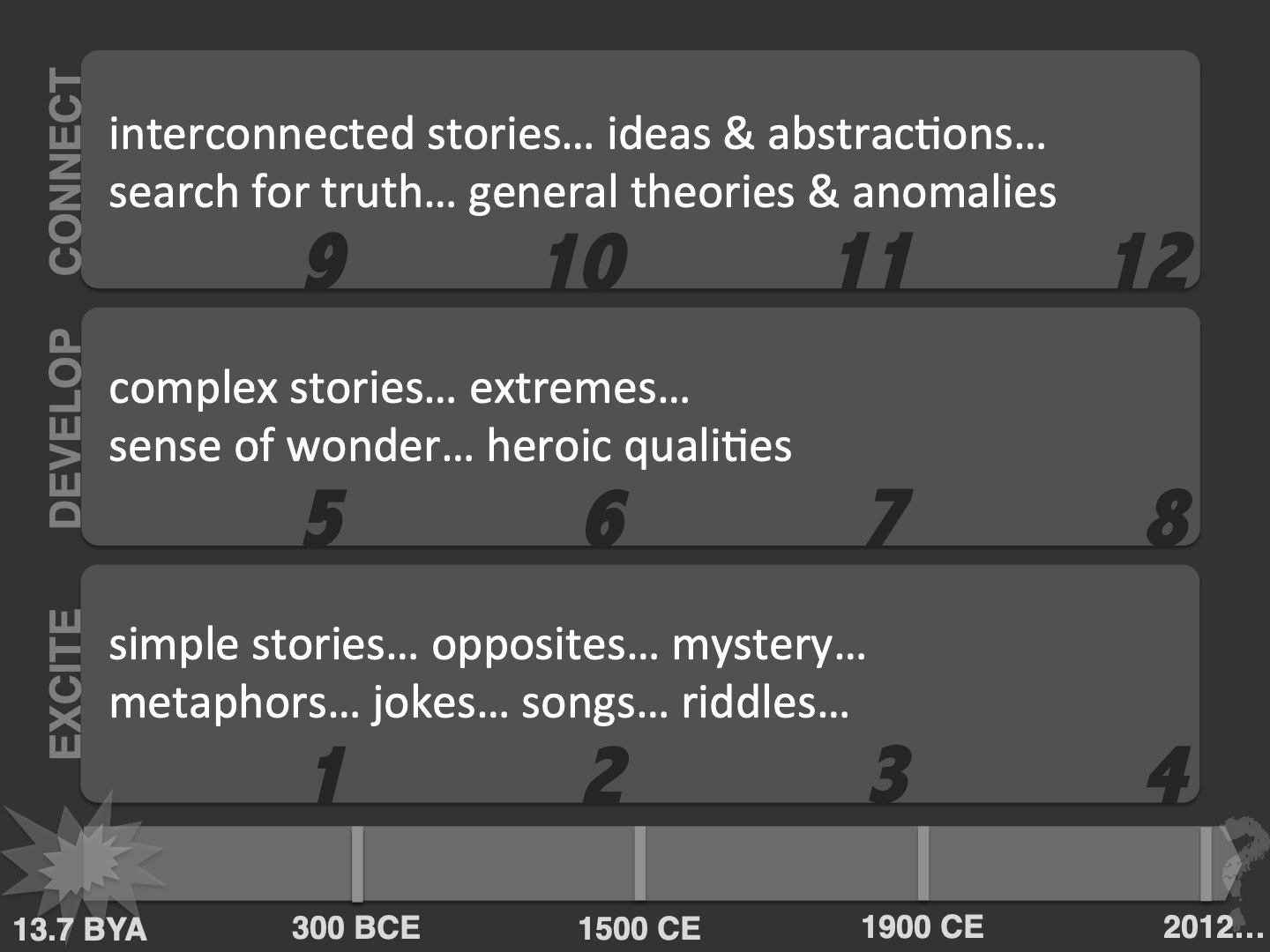

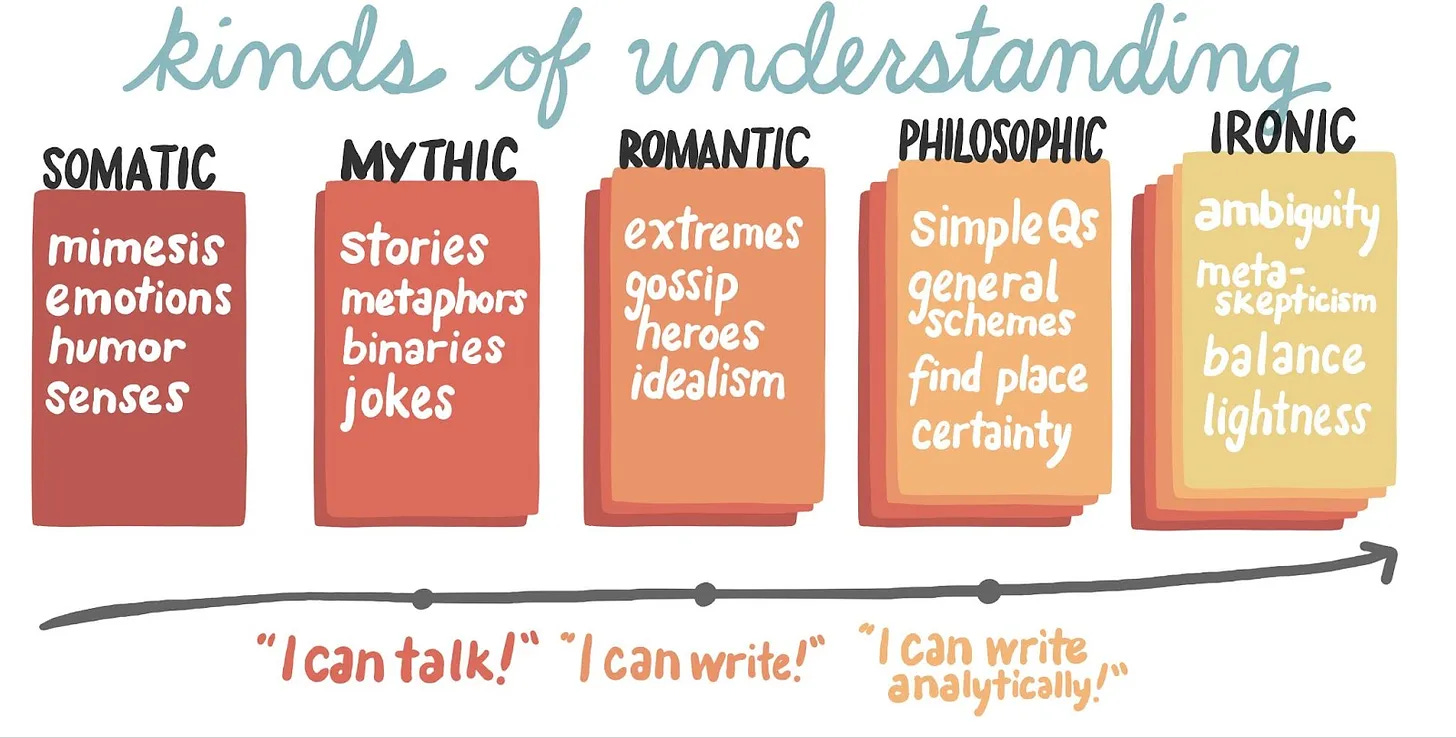

The other backbone of an Egan education, of course, is the different ways of understanding that we gradually build:

As kids expand their ways of understanding the world, we want to revisit the old stories. (Which is to say: it really seems that these two backbones should support each other.)1

2. Basic plan

In elementary school, excite kids with the epic span of the whole world with simple stories. In grade 1, start with the Big Bang, and share stories up to around the year 300 BCE. In grade 2, share stories from there up to 1750 CE. In grade 3, share stories up to 1945 CE. Finally, in grade 4, cover the postwar world up until today — and imagine the future.

In middle school, start over with a new cycle. Starting in grade 5,2 follow the same rough division of history to develop the story of the world. Use complex stories to go much deeper than before. Complicate students’ understandings!

Then in high school (ninth grade), start over for one final cycle. This time, introduce abstractions (the big ideas that academics chew on, digest, and poop out) to connect what they’ve learned. Once again, complicate their understandings whenever possible.

3. What you might see

In grades 1–4, kids enjoying simple stories, and teachers not terribly worried about getting the chronology exact. In grade 5–8, kids peeking ahead to see which of their favorite stories will be revisited. In grades 9–12, eyes lighting up as students see that what had been cool details of a story actually played a part in the big story of life, the Universe, and Everything.

If you’d like one example of how a story might be re-explored, take a look at a paper I presented at the inaugural International Big History Association conference — specifically about two-thirds of the way through (do a control–f for “Darwin”).

4. Why?

The usual “scope and sequence” of social studies — at least in America — only makes sense if you understand that it’s a century-old compromise from a particularly nasty divorce.

The first seven years went to the Educational Progressivists. They were excited to make use of an idea from developmental psychology which was then in vogue: that children can best make sense of the world if they start with themselves, and only slowly move outwards —

kindergarten: themselves

grade 1: their families

grade 2: their neighborhood

grade 3: their city

grade 4: their state

grade 5: their country

grade 6: the contemporary world3

That was one half of the settlement. The final six years went to the Educational Traditionalists, who basically said, “to hell with modern psychology — let’s just put the most important stuff into kids’ heads” —

grade 7: world geography/world history

grade 8: American history

grade 9: civics/world cultures

grade 10: world history

grade 11: American history

grade 12: American government4

At the time, no doubt, this seemed judicious. But a hundred years later, I mean my goodness, just look at this! The first half seems hell-bent on making kids short-sighted and self-obsessed — and dare I say xenophobic? Very little of the non-Western is brought in. (There are reasons developmental psychologists have fallen out of love with this idea.)

Meanwhile the second half crams in a jumble of content — again, mostly focusing on the parts of the world that are closest to kids — in no particular order. And, yet again, it doesn’t feature much of the story of the outside world! As much time is given to the American experience as the rest of humanity combined.

As a lover of American history who loves to teach American history and has a degree in American history, I’ve gotta say: American history isn’t THIS important. And if you don’t understand the context in which American (and Western) history sits, you’ll never really understand it at all.

Worst of all, this “let’s waste time then rush” approach seems guaranteed to raise kids who don’t like history! We’re throwing away the early years, when kids enjoy learning through simple stories.

If a good compromise leaves everyone mad, this is a fan-freaking-tastic compromise.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Who hasn’t had the experience of re-watching a beloved childhood film (or re-reading a beloved childhood novel) as an adult, only to discover it was totally different than we’d first found it?

As Marcel Proust famously put it: “The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.” We want to provide many chances for our kids to see something old with new eyes.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

Because this pattern involves returning to the same things, it ends up being a workhorse of developing different kinds of understanding — especially the middle three.

It would be too blithe to say we use 🧙♂️SIMPLE STORIES in elementary school, 🦹♂️COMPLEX STORIES in middle school, and 👩🔬METANARRATIVES in high school, but that wouldn’t be a terrible place to start. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

In ROMANTIC (🦹♂️) understanding, we also want to make use of 🦹♂️HEROES who have 🦹♂️COMPLEX INNER LIVES. And in PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) understanding, we want to use these by-now-well-known stories to be the foundation of 👩🔬SYSTEMS THINKING.

But don’t take these divisions too seriously. Remember these ways of understanding don’t replace each other, they overlap. Moreover, kids start to develop all of them quite early on, so we want to be presaging (say) Philosophic tools even in the earliest grades.

6. This might be especially useful for…

People who really, really, really like history — which, with this sort of education, will begin to describe a much higher fraction of the population than at present.

7. Critical questions

Q: Brandon, just THINK about what you’re suggesting — how could this sort of education handle kids who transfer into Egan education in the later years? This could never work in practice.

I agree that this is a problem — as is every pattern that involves cumulative content. The trouble is that if we take this objection at face value, we’d have to abandon every topic at the end of the year.

Which, sadly, actually describes a lot of education at present! This concern helps give us the assembly-line model of schooling: topics appear out of nowhere, are worked on, and then are taken away, never to be seen again. This is a large part of why learning feels so pointless.

(It’s also why you can spend literal months every single year re-learning how to, say, type up a “works cited” list in MLA format.)

This is a challenge to be solved, not a reason to throw up our hands.

Q: Okay, well, what solutions do you have?

I think that kids who transfer into an Egan middle school or high school might get a quick review. If a school is extra demanding, it might even give prospective applicants study materials, and proctor a test.

I’m interested in other ideas y’all have.5

Disaster springs eternal in the human breast: can you think of another way this could go so exquisitely wrong? Frankly, WE WOULD LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT IT. Subscribe and join in the comments conversation.

8. Physical space

Y’know, sometimes life is sweet; some patterns don’t require clever uses of physical space.

9. Who else is doing this?

THANK YOU THANK YOU SUSAN WISE BAUER.

Wait, you don’t know Susan Wise Bauer?! Susan Wise Bauer6 is the person who put classical education on the homeschooling map with her book The Well-Trained Mind: A Guide to Classical Education at Home in 1999.

At the center of her curriculum is a spiraling scope and sequence of history:

grades 1, 5, 9: Ancient times (nomads to the fall of the Roman Empire)

grades 2, 6, 10: Middle ages (fall of Rome to early Renaissance)

grades 3, 7, 11: Early modern times (Renaissance to 1800s)

grades 4, 8, 12: The modern age (1900 to now)

An attentive reader might note some small differences here — this only goes back to the birth of civilization (rather than the birth of the Universe); it follows a more European-oriented framing; it stops at the present, rather than contemplating the future.

The biggest difference, though, is what powers the cycles. Bauer is a proponent of the Trivium, which takes as its model the educational approach of ancient Roman aristocrats: grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

Or, well, maybe I should say “grammar”, “logic”, and “rhetoric” — to repurpose the classical model to the developmental needs of children, those terms end up getting redefined — for example, “grammar” ends up meaning “memorize a lot of stuff”. But my take on classical schooling is the topic of a future post. The upshot of this is that this is a great opportunity for us to apply Egan’s paradigm to give us ideas for how to teach the stories in each cycle.

Q: Hey, wait, Brandon — if you’re getting this from SWB, then what did Egan himself recommend? And why do you think this is better?

Funny story, that.

You might remember in my ACX book review of Egan’s Educated Mind some sections that were REALLY LONG LISTS OF COOL-SOUNDING HISTORY THINGS. Like:

in first grade we can tell kids the stories of the war of the Greek city-states against the Persian empire, and the slave uprising of Spartacus against the Romans. We can tell them about the plight of Jews in medieval Europe, and of the unsuccessful Sepoy Rebellion in India against the British. We can tell the stories of the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions, and about the Chinese Taiping Rebellion against the Qing Dynasty. We can tell them the story of the escaped slave Harriet Tubman returning to the South to rescue her kinsmen, the story of six-year-old Ruby Bridges facing threats to integrate her elementary school, and the story of how the Mau-Mau uprising led to modern-day Kenya. We can tell the stories of Mexican-American union organizer Cesar Chavez and of Malala Yousafzai surviving an assassination attempt to advocate for female literacy. The world does not lack for stories of oppression and liberation that can capture the attention of a six-year-old.

It’s that last line that gives Egan’s notion for how to organize the scope and sequence of history in the early grades: pick one binary per year (like oppression/liberation), and tell as many stories as possible, pulling from every time and every culture. Do the same thing the next year except with a different binary — danger/security for grade 2, and ignorance/knowledge for grade 3.

And, honestly, this approach has its elegance! But I remember driving up from Seattle to Simon Fraser University back in 2012. “Nervous” doesn’t begin to describe my state. After discovering one of Egan’s books in an academic library, I had fallen in love with his ideas, and had gotten to meet him briefly after he happened to give a local talk.

Kristin and I had decided that we were willing to uproot our family and move to Canada so I could become his PhD student.

First I showed him Anki, the spaced-repetition flashcard system, and sketched out my ideas for how it could be used to secure the most exciting knowledge kids had learned. Kieran’s response was… I think “polite” would be the term.7

Then I began to describe my proposal for Big Spiral History. His eyebrows began to animate. He took my printed copy of the proposal and began to speed-read it, wolfing it down, nodding excitedly, barely even listening to me.

He liked it. A lot.

I ended up not being able to be his PhD student — he had, it turned out, just announced his intention to retire — but he invited me to present Big Spiral History officially at a conference he was organizing.

How might we start small, now?

Well, you might enjoy my proposal! (If you read my book review and found yourself thinking “why isn’t this longer?”, count this as an early birthday present.) Or, if you’re short on time, take a spin through this set of pretty slides.

And then, we can start listing — in the comments section below — books and YouTube channels and other places we can lean on to help us create this. I’ll start by suggesting two of my favorite sources —

Susan Wise Bauer’s The Story of the World: History for Classical Child. This is a four-book series; each chapter is a short story.

Larry Gonick — the masters-in-math-from-MIT-turned-cartoonist polymath — has a series of comic books which tell the story of the entire Universe.8 They start with the three-volume The Cartoon History of the Universe I, II, and III, and end with The Cartoon History of the Modern World Part 1 and Part 2. They’re just FANTASTIC: his knack for telling a good quick story (and for choosing the best stories to tell) would make this my favorite world history even if this was just prose; that they’re comics raises this to another level entirely.

(Classical homeschoolers, you’re better at recommending quality history books than any human has a right to be at ANYTHING. Fire away!)

10. Related patterns

Spiral History° completes Big History° (hence the not-so-profound name “Big Spiral History”), telling us when to teach what, and which tools to use. The first two cycles should be explored through Epic Stories°; I suspect the final cycle should be explored through Metaknowledge°. We can keep all this stuff straight — and help relate it to each other — through Nested Timelines° and Geography by Heart°.

Knowing something specific about all sorts of other places and times lets us load up elementary school with rich aesthetic experiences like A Song a Week° and A Painting a Week°, and with other bits of thought-provoking cultural products like Other Alphabets° and World Proverbs°.

Which reminds me: this also allows even young kids to start to ask big questions about life, the Universe, and Everything — thus supporting Philosophy Everywhere°, and allowing them to start wondering about the deep story behind their Learning in Depth° topic.

Afterword:

I’m on vacation right now outside of San Antonio to see the Great American Solar Eclipse of 2024 That Probably Will Be Ruined By Cloud Cover.9 That’s to say that (1) I’m falling behind on everything, and (2) I’m coming up with some big new ideas. Like, for example, I think I’ve been explaining the Philosophic Toolkit all wrong to everyone for years. (!!!)

This realization has been sparked by working on the upcoming Learning in Depth Summer Intensive, which I’m getting more and more excited about. Look for some new information about that soon. (Especially you people who signed up to get new information! Sorry to be taking so long!)

I’m also getting excited about going deep into the debates over Jonathan Haidt’s new book, The Anxious Generation. If you’d like to dip your toes in it, I recommend starting with his conversation with Yascha Mounk followed by his conversation with Tyler Cowen (who’s more critical).

Arguably it also says that “backbone” wasn’t the best metaphor I could’ve gone with.

Which we’ll call “middle school”, because isn’t it nice when you can divide things into three equal sets?

America is notorious for its lack of a unified curriculum; your mileage may vary. (Um, especially if you didn’t go to school in America!) (Actually, we’ve got readers from around the world — if your experience was different than this, would you be willing to throw it into the comments?)

Maybe you think I’m creating a strawman here? Nope. I’m pulling this specific list from the wonderful Walter Parker’s 1991 Renewing the Social Studies Curriculum, and Walter didn’t cite it to be critical.

I’ve always like the word “y’all”, but I’m a Northerner, and I’m usually a bit nervous that someone will yell DIE, CULTURAL APPROPRIATOR SCUM! at me whenever I say it. But I’m vacationing in Texas right now, and frankly it’d feel weird not to say it.

Called “SWB” by the cool kids, but I am most assuredly not a cool kid here.

By and by, I’ll be sketching the role I think space repetition should play in Egan education. I should probably write a reminder to explain why I think Kieran was so cool on the idea, and why I think we should do it anyway. If you’re interested in the meantime, you’ll want to read TanagraBeast’s classic LessWrong post on his experiences.

He created them over a series of thirty-two years, which amounts to a not-insignificant fraction of the period his books recount.

Are you familiar with "A Little History of the World"? https://www.amazon.com/Little-History-World-Histories/dp/030014332X

I think it's the perfect history book to read aloud with 3rd or 4th graders. It's written to be approachable, and with a passion that comes through on every page.

Also, why 3 cycles of 4? Couldn't prehistory and future contemplation be moved into their own years, creating 2 cycles of 6?