(Note: This afternoon, we’ll be doing a live preview of our Learning in Depth summer intensive! See the bottom for details.)

1. A problem

When we don’t know where things are, we’re stupid — no matter how smart we are otherwise.

If you don’t know where (just to pick a few non-random examples) “Ukraine” or “Iran” or “Maryland” are, you’ll always struggle to understand the world. When you hear these names, they’ll whoosh past you. Your knowledge of the world won’t accumulate; it’ll evaporate.

2. Basic plan

Have students commit the most important features of the world to memory.

Starting in first grade, learn to identify the most obvious features of the world — the continents and the oceans. Move to the major countries, then the major cities, then the coolest geographic features (the highest mountains, the driest deserts, the biggest rivers, the most ecologically rich rainforests and reefs…).

Slowly, move to completion — learning all the countries in (say) South America, all the states/provinces/territories in your nation, all the U.N. member nations…

3. What you might see

Kids who know their world.

First graders who know where Africa and Antartica are. Third graders quizzing Seterra.com daily, and being wicked fast at tapping out countries. Fifth graders playing The Geography Game° in the weekly Brain Bowl°. Seventh graders who talk about what’s going on in Eritrea1. Ninth graders who know all 195 UN-recognized countries, and the major rainforests, deserts, rivers, and mountain ranges.

4. Why?

Back when I was an SAT coach in Seattle, I was getting to know a new student. We had just finished a riveting conversation about how Watson & Crick discovered DNA (and how Rosalind Franklin was shortchanged).2 Very smart teenager. And then, offhandedly, I mentioned something about the Pacific Ocean.

“The what?” he asked.

The Pacific Ocean, I replied — the, um, Pacific Ocean.

“What’s that?” He was genuinely curious.

I apologized: I must not be speaking clearly, and the Starbucks we were in was pretty loud. I pulled up Google Maps, and showed him where we were, and zoomed out to the Pacific Ocean next to us.

His eyes went wide.

He told me he had never learned about the Pacific Ocean.

“What did you think was between us and China?” I asked. He said he had never thought about it before.3

It only takes a few minutes to acquaint ourselves with the world’s most important features, yet schools sometimes don’t do it.4

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Actually, this predates humans! As we talked about in Art of Memory°, place is special: mammals literally have special cells (“grid cells”) in our brains that automatically draw a map of our surroundings.

Physical maps extend this, and allow people to talk about place. Some maps go back to Babylon; some may go back to our mammoth-hunting days.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

The missing piece of elementary school is world history, and geography is the stage on which history happens. That’s to say, 🤸♀️LOCATION is the grounding of 🧙♂️SIMPLE STORIES, and those are the foundation of 🦹♂️COMPLEX STORIES and even 👩🔬METANARRATIVES.

(What do these weird emoji mean?) 🤸♀️🧙♂️🦹♂️👩🔬😏

6. This might be especially useful for…

Peacocks who love to preen.

7. Critical questions

Q: Earlier you mentioned kids should start with the “major” countries? And which, specifically, would those be?

Great question. I think that—

Q: Are they the WESTERN ones? Are you smuggling in some exclusive politico-cultural vision here?

— as I was saying, as we decide which countries to—

Q: Way to STEP in it, Brandon!

I think the answer is that, in the end, it doesn’t much matter, precisely because we are headed to completion. Eventually, the students will learn all the countries.

Q: But what if they don’t? What if they bail halfway through?

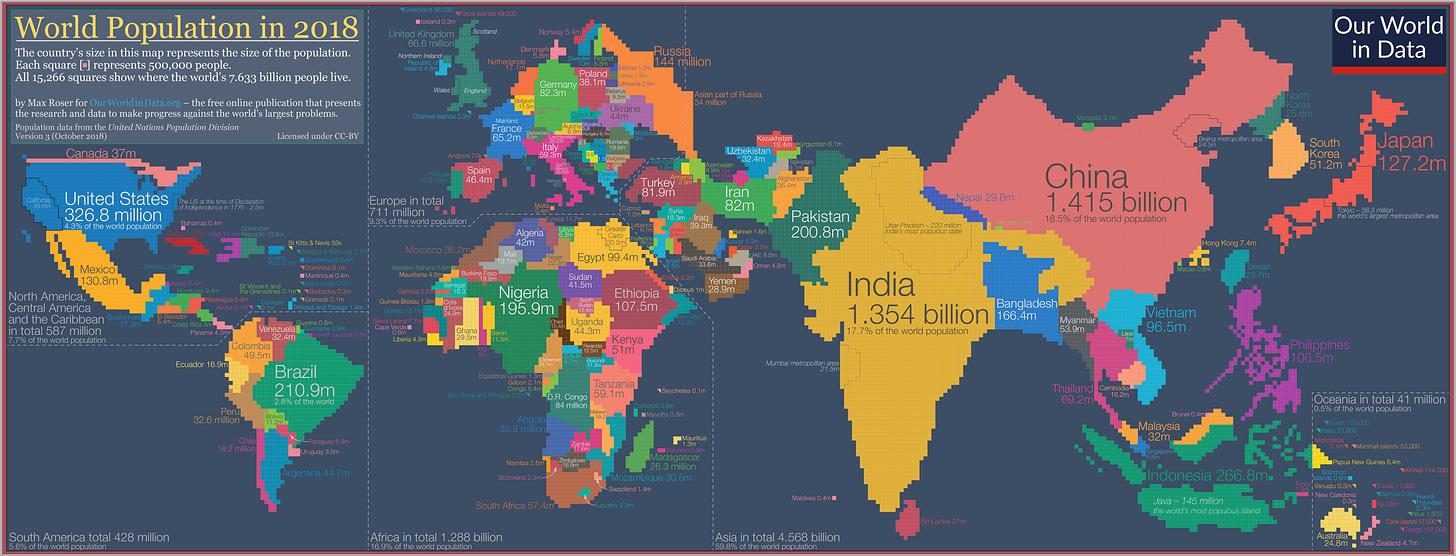

That’s a real possibility — so yes, we want to front-load what we think are some of the more important things. When I do this,5 after doing the continents and oceans, I start students on the most populous countries:

Going by population is a pretty good way to sidestep this “which countries are most important” problem.

Q: I’m hearing you say “memorize this information”. But how useful is this?

When I taught at the Educationally Progressivist school outside Seattle, I remember another teacher saying that learning facts was foolish, because facts change all the time.

In the moment I didn’t say anything. As I’ve reflected on this over the years, I’ve realized that, well, some facts don’t. Barring some really interesting tectonic events, the Indian Ocean will still be there when our students are adults. Ditto Antartica. Ditto Turkey.

Q: But isn’t all of this just stuff you can look up in a book, or on Wikipedia, or whatever?

If you need to keeping looking up where “Palestine” is, you’re not going to be able to follow a conversation about the war in Gaza. (And if you aren’t holding in your head where the Gaza Strip, the Jordan River, and the Mediterranean Sea are, you won’t be able to come up with anything useful to add to the conversation.)

Q: Okay, but not all conflicts are so tightly tied to specific places.

Agreed — but world events are a story, and the story has a setting. If you don’t know the setting, you simply can’t make sense of what’s going on.

Q: Why don’t all schools ALREADY teach the world’s continents and rivers and countries?

This goes back to something we talked about before — about how now-standard “scope and sequence” of social studies is a century-old compromise from a particularly nasty divorce. The Educational Progressivists (who had got most of the elementary school curriculum) scrubbed out most of the history from the curriculum and replaced it with topics they thought were more meaningful and relevant. The Educational Traditionalists (who had got most of the middle and high school curriculum)… well, here I’m just guessing.

Was it that they didn’t realize their incoming students hadn’t learned much geography? Was it that they were enough influenced by Educational Progressivist professors that they thought “rote learning” was pointless? Was it that they thought sitting kids down to memorize country names was beneath them?

All I know is that I asked that smart high school student (who, it must be said, had gone to some of the best-rated schools in the Seattle area) if he had ever been asked to label a map, and he said yes, once — in a Spanish class, he had been asked to memorize the provinces of Spain.

Q: Maybe the bigger problem is just that there’s no longer any coherent vision of what the curriculum should be.

I wonder that, sometimes.

Q: How is any of this particularly Egan-y, though?

Good question! What I’m sketching out here is fairly Traditionalist: it focuses on remembering the names. That has the virtue of being simple, and is more than good enough to start.

Q: What would an Egan-fueled geography curriculum include?

It’d go further, and connect places with 🧙♂️VIVID IMAGES. So when you learn the location of the Great Barrier Reef, you should see a photograph of it — something that evokes a feeling, and sticks in your mind.

Ditto for the Gobi Desert:

Going even further, a fully Eganized geography curriculum (for elementary school) might include…

amazing facts: “The Cone Snail, one of the world’s deadliest animals, lives on the Great Barrier Reef. Don’t pet the snails!”

stories: “Adventurer Roy Chapman Andrews, the inspiration for Indiana Jones, went to the Gobi Desert to find bones of the first humans. Instead, he became the first person to ever find dinosaur eggs!”

You get the idea.6

Can you think of another way this could go terribly, terribly wrong? Frankly, WE WOULD LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT IT. Become a paid subscriber and join in the comments conversation.

8. Physical space

At home

Google Earth is probably the single greatest map that’s ever existed — but just as photographers say “the best camera is the one you have with you”, the best map is the one you can point to in two seconds, without opening an app.

That’s to say: you’ll want a map of the world on your wall.

In a classroom

Got lots of wall space? Put up more kinds of maps! Go beyond national boundaries and have one that shows biomes, or population density, or just terrain. Show one that’s delightfully out-of-date, or shows the world’s charismatic megafauna or mythical monsters. Throw up a few radically different projections. Or put up the one that shows the Earth right-side up.

9. Who else is doing this?

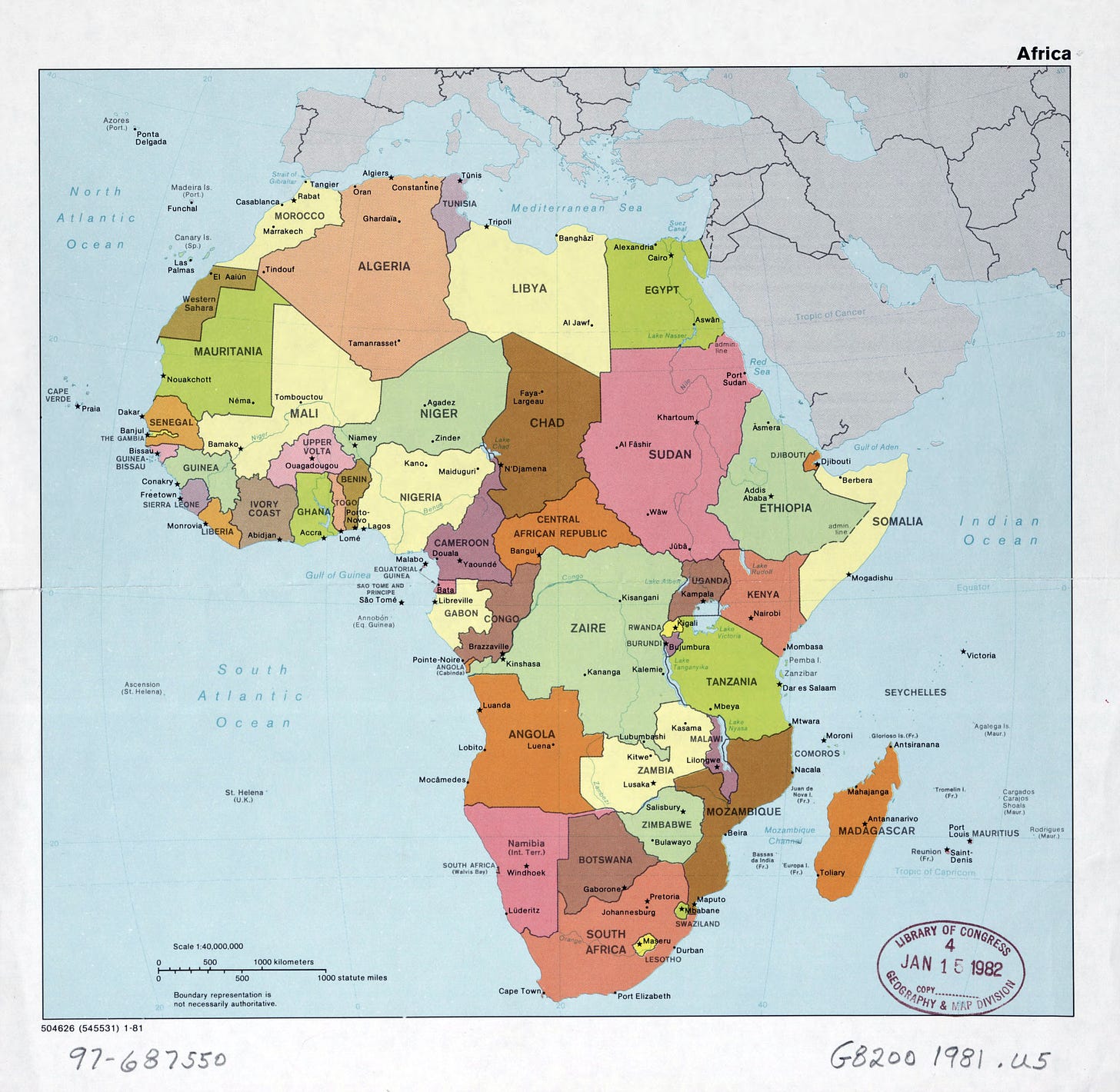

The classical education people take geography seriously. When I was in high school, I babysat two kids I knew from church. They were only maybe seven and nine, but I recall vividly how they could identify the countries of Africa — all the countries of Africa, even the ones that Americans barely know exist — more quickly than I could tell you the names of the first 100 Pokémon.

And the classical education folks didn’t invent the whole “learn the names of geography things” out of the blue — they’re just resurrecting what used to be bog-standard normal in education.

So this pattern isn’t some exciting innovation — it’s (mostly) just to return to what worked for a long time, perhaps with some Egan frills.

How might we start small, now?

With your child (or spouse, or friend) write down what you think the 10 most populous nations in the world are. Then, check it with the map above.7 Now, go to this custom Seterra map, and see if you can get them all right. (If not, do it again. If you still struggle, do it again!)

Beyond that, you can do basically everything we’re saying here (minus the Egan frills) in Seterra. (Warning: I’ve found that Seterra can become mildly addictive.)

10. Related patterns

Look — geography is the literal “base” for making sense of Big History°. Since Big Spiral History is the backbone of the entire curriculum, that means that this pattern connects to everything.

I’m going grit my teeth hard, and not provide links to everything here. A special shout-out should go, though, to Geeky Songs° — some of which make it easy to memorize the nations of the world, or the U.S. states and territories, or whatever.

But “pointing to stuff on a map” isn’t the end of geography, and a few other patterns that will take us further into understanding the world: Drawing Maps° puts kids in the cartographers seat, and Shading Maps° helps them use maps to upset their assumptions about the world.

Afterword:

This afternoon we’re holding a live preview for our Learning in Depth summer intensive!

In this cohort, you’ll learn how to go from noob to expert in anything, fast. You’ll also learn to use our modern tools (especially ChatGPT) to grow deep human understanding.

3pm Eastern Daylight / 12pm Pacific Daylight

Saturday, 11 May 2024

If you’re interested in joining the preview, just fill out this form. (I’ll send out a link sometime in the hour before we start. If you miss it, don’t fret — it’ll be recorded.)

Africa’s North Korea™.

Authorial note: this sentence has two problems, and I’m interested in getting your advice. First, I know that Watson and Crick didn’t “discover DNA” — DNA had been known about for a long time; their breakthrough was in understanding that it was where the genetic code was located. What I don’t know is how to express this in a short phrase. Second, I think the word “shortchanged” undersells what was done to Rosalind Franklin. (Well, arguably — this is actually a little contentious.) The word my brain fills in is “gypped” — but given the depredations that the Gypsies (aka the Roma) have undergone in the 20th century, I’m trying to wean myself away from that word. I haven’t yet found a word or phrase, though, that quite does the same thing. If anyone has suggestions for either of these, I’d love to hear ‘em in the comments. (The usual warnings of “any comments touching the culture war will be deleted” apply here.)

It actually gets a little worse: I found out that his family owned a second house on the Puget Sound, which is an inlet of the Salish Sea, which is part of the Pacific Ocean. That is: he literally lived on the single largest thing in the world, and didn’t know about it.

I later had the opportunity to meet Howard Blumenthal, the guy who created the classic PBS geography gameshow Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? I later found out that what drove him to do it… was reading a study showing that many Americans couldn’t find the Pacific Ocean on a map.

I’ve tied this into the first year of the Science is WEIRD curriculum, because even understanding science requires understanding geography.

If anyone is serious about making such a curriculum and would like to kick around ideas, shoot me a message; I’d love to do a 30-minute Zoom.

Or this Wikipedia page, which is bit more up to date.

Okay, I actually count four countries in Africa that have changed their name since 1982:

- Upper Volta -> Burkina Faso

- Zaire -> Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Swaziland -> Eswatini

- Ivory Coast -> Côte d'Ivoire (According to Wikipedia, the government made the French name the official name in 1986.)

The two new countries are South Sudan and Eritrea.

Both of my kids attended Montessori schools starting in preschool where they studied the flags, capitals, countries and made beautifully detailed maps they would bring home. But that geographical knowledge sadly didn't seem to carry forward into the Elementary Levels and there didn't seem to be many opportunities to review/revisit this knowledge and so much has been forgotten. I was glad to learn about Seterra earlier this year. My middle schooler and I have incorporated Seterra into our homeschool activities and she typically out performs me, perhaps she's remembering things she learned many years ago in preschool?