1. A problem

Before kids face polynomials, they should probably learn multiplication — and before they face multiplication, they should probably learn addition! That’s to say: before we teach the complex things, we should teach the simpler things that make ‘em up.

Imaginary Interlocutor: This seems obvious.

Indeed, it does! And in math, we do this. (It’s actually hard to imagine a math curriculum structured in another way.)

Yet in most of the other subjects, we ignore this. Topics routinely get repeated, or skipped, or just crammed in at the end. This reduces much of what kids learn to trivia: they don’t have confidence it’ll be needed in the future.

2. Basic plan

Pay the rest of the subjects (history, science, writing, art…) the respect we give math: make what’s learned useful by thoughtfully linking it up together. Help knowledge grow and intertwine and become something amazing.

3. What you might see

In history, students making comparisons to a culture that was explored two years back.

In art, deep dives into very particular painting movements (Baroque, Neoclassicism, Realism, Post-Impressionism, Afro-Futurism…) over many years with the hope that each movement will be new and potentially surprising to the kids.

In writing, topic sentences being taught once, and then never again.

In science, the conception of atoms being taught simply — they’re balls!…

…then again with more complexity — they’re Bohr models of subatomic particles with weird agendas:

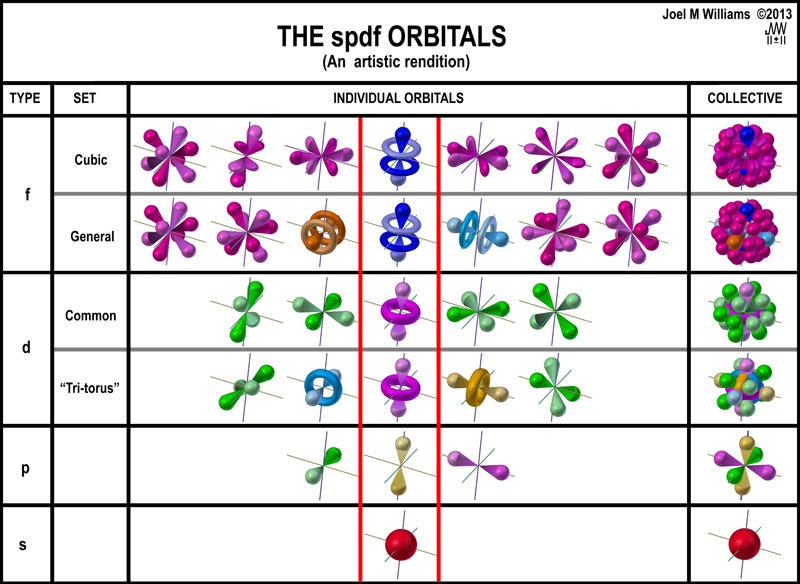

…then with even more — an atom’s shape is actually its the type of orbitals that its electrons form:

…all the way up to Schrödinger’s equation:

4. Why?

This gives elementary school in particular a vital mission: secure in students’ minds the simplest pieces of knowledge (the literal elements) that the rest of the curriculum will build on.

My hunch is that, by and by, this will elevate the status that elementary school teachers have in our society.1

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

The early years might matter the most.

Every major educational thinker has emphasized the crucial importance of the early years of education.

And yet, if we consider our schools today, it is hard to believe that the predominantly provincial trivia of the curriculum and the worksheet-oriented or ‘hands-on’ activities of common teaching practice are adequate responses to the importance of the task.

–Kieran Egan, The Educated Mind

Q: What the heck happened?

Answer: the asinine, century-long war between the Educational Traditionalists and the Educational Progressivists.2 There was a fight, and they broke up. In the divorce settlement, the Traditionalists got the high school, and the Progressivists got the elementary school.3

Educational Traditionalists tend to be concerned with getting the right content into people’s heads — hence the amount of academic, discipline-oriented classes in high school. Educational Progressivists tend to be concerned with developing the student well — hence the focus on creativity, on developing “a lifelong love of learning”, and on “who am I?” activities.

Egan’s insight is that this split was stupid: students develop creativity by playing with meaningful content. They learn to love meaningful content. Heck, they come to understand themselves through meaningful content.

The trick is to give them that content not by dumping more facts into their heads, but by using the right tools.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

It’s more a question of how the different kinds of understanding allow for this to work. Remember that one of the projects of Educational Progressivism has been figuring out what’s “developmentally appropriate”, and then scrubbing it out of the early years. But Egan points out that even young kids can understand most things — if they’re taught through the right tools.

Start by using the SOMATIC (🤸♀️) and MYTHIC (🧙♂️) tools that even young kids are quite good at — especially EMOTIONS and STORIES and METAPHORS. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

Then, beginning around third and fourth grade, begin to lean more on ROMANTIC (🦹♂️) tools, especially IDEALISM and THE LIMITS OF REALITY.

Then, beginning in high school, begin to lean more on PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) tools, like BIG QUESTIONS and WARRING IDEOLOGIES.

In doing this, we give both sides more of what they want: Progressives get individualization and meaning and creativity; Traditionalists get all the content, content, content their hearts desire.

6. This might be especially useful for…

People who wish they had learned about topic sentences just once, and then were flipping done with it.

7. Critical questions

Q: There are two obvious problems. The first is that PEOPLE FORGET THINGS. It’s nice and all to suppose that kids will carry their knowledge through from year to year, but most of them won’t — they won’t retain it long enough to re-use it.

A big part of the reason students forget what they’ve learned is precisely because they don’t re-use it.

Daniel Willingham, in his book Why Don’t Students Like School? A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions about How the Mind Works and What it Means for the Classroom,4 points to an intriguing study:

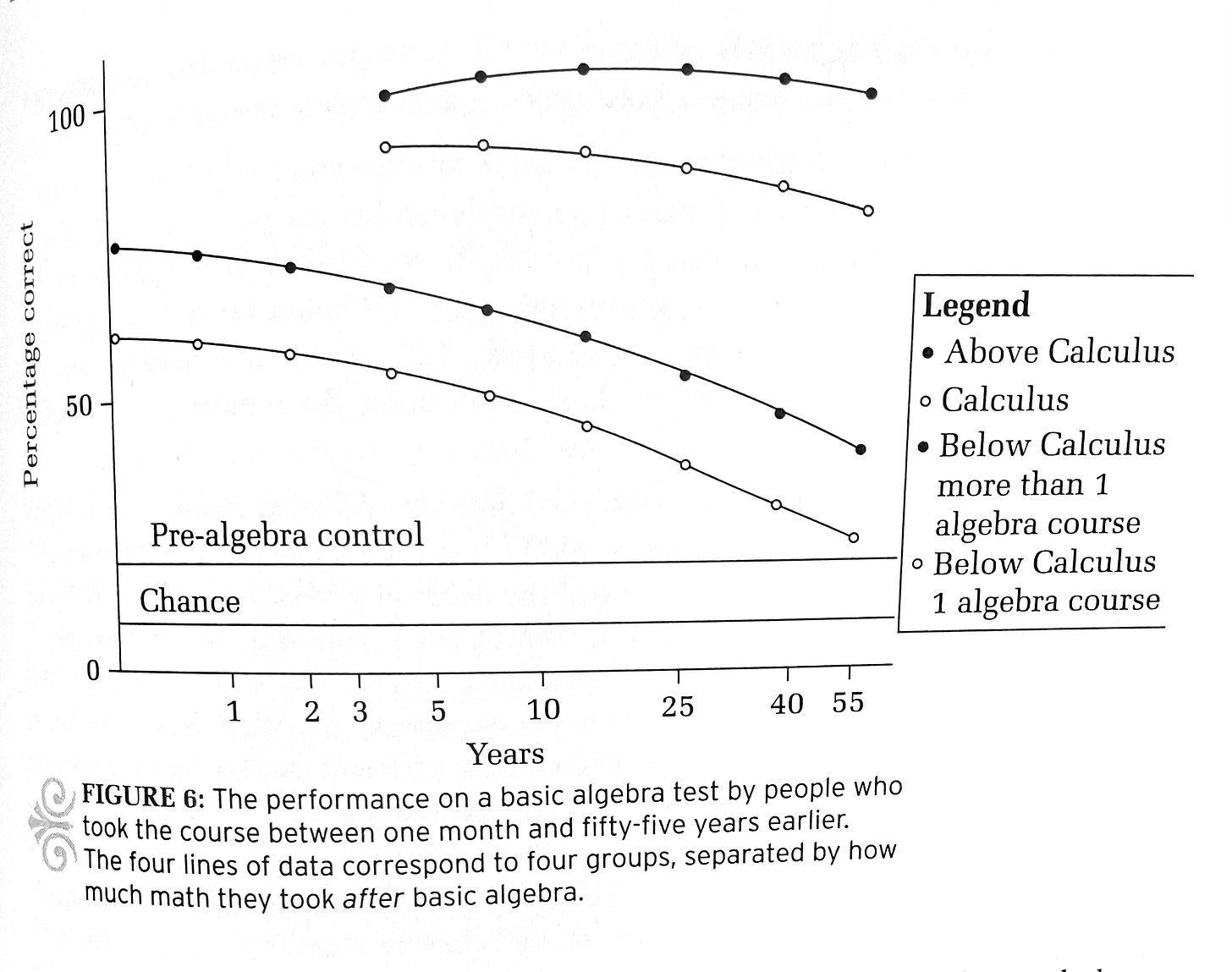

The graph is fun to unpack — feel free to take a minute on your own to puzzle it out — but it looks at how well people were able to solve algebra problems years after they took algebra.

You might expect their skill to follow a typical forgetting curve — it’d just go down. But there’s a twist: they looked at four groups of people, broken up into whether they kept working on math after algebra.

People who stopped at one algebra course? Their abilities diminished until they had forgotten all of it. People who took another algebra course? They did a bit better. People who kept going until calculus? Better still. And people who went beyond calculus? They never lost their algebra skills.

Q: “People who went above calculus” are not normal people; they’re brilliant rocket scientists or whatever who are going to be using math on a daily basis and, and…

Yes, no doubt there are confounders here. But the principle seems strong: if you keep using something, you won’t forget it.

And indeed we see that with K–12 math: though it’s been decades since I’ve learned to to multiply, I daresay I know how to do it better now than I did when I was eight!5 We can expect that something similar will happen with history, and art, and writing, and music, and everything else we help kids do.

Q: But they WILL forget things.

Of course — which is we want to have practices that take forgetting seriously, and address it systematically. (See the patterns below for this.) That said, a little forgetting is a fine thing.

Q: My second concern is the opposite: insofar as students DO remember what they’ve learned, it makes it difficult for new students to enter the school! They’ll be forever behind.

This could become a real concern, but, I think, a manageable one.

We could address it through on-ramping procedures for new families: think, “to enter our middle school program, you have to become acquainted with x, y, and z; there will be a test. You might want to read these books, and watch videos from these YouTube channels.”

I suspect that’ll work for the utter basics — getting kids up and running with the fundamentals. For all the complex untestable stuff, we should trust in the power of culture to help new kids soak up knowledge from their peers. (That, after all, is how a culture works.)

But look: if this becomes a big problem, it’ll mean that we’re succeeding at helping kids actually learn! Flip it around. Imagine a school in which it doesn’t matter at all if you’ve studied the curriculum in the years before — students can just enter at any time based on when they were born. Would you want to send your kid to that school?

Can you think of another way this could go terribly, terribly wrong? Frankly, WE WOULD LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT IT. Become a paid subscriber and join in the comments conversation.

8. Classroom setup

For those of us who are starting schools, this raises again the question of whether elementary and middle school students should switch teachers each year, or whether a teacher should follow a class through multiple years. (We should, um, really look into that, some day.)

9. Who else is doing this?

I have a hunch that this is a significant part of what make Montessori, Waldorf, and International Baccalaureate schools more enjoyable for students and teachers. Each has a unified vision of what should be taught, and when — going through the curriculum feels more purposeful.

(That said, I’ve never been a student in either kind of school, so I might be totally wrong about this.6)

And this is, of course, one of the biggest reasons some families choose homeschooling — they can focus on what a kid actually doesn’t know, rather than having to repeat, repeat, repeat what others have forgotten.

How could we start small, now?

With our kids (and ourselves), we do this naturally! So, cheerfully, there’s not much to improve on now.

10. Related patterns

This is one of those meta-patterns that shapes so many specifics.

Spiral History° and All the Sciences at Once° (which is how I’m organizing the Science is WEIRD curriculum) give an order to the chaos of introducing, exploring, and connecting the different aspects of whole subjects.

One key for memory is having reminders. You might remember The Art of Memory° from last week,7 but patterns like Nested Timelines° (June 19) and Size Lines° involve creating physical reminders in the classroom, and patterns like Local Birds° (May 3), Local Trees°, Local Bugs°, Local Flowers° and Star Lore° use common physical things as reminders.

Some patterns point us to helping kids learn the fundamental pieces early, so they can be given more complexity later: Atoms on Up° (which I sketched out here) and Evolution Throughout° in science, and Geography by Heart° (May 1), World Religions Throughout° (July 12), Everyone Learns Law°, and Everyone Learns Economics° in the humanities.

Afterword:

Oh, jeez, I need to schedule another book club, don’t I?! Look for that soon…

At present, we mostly pretend to honor them. (When I was a third, fourth, and fifth grade classroom teacher, it took me a while to figure this out.)

To be fair, “the asinine, century-long war between Traditionalists and Progressivists” is the answer to most problems in education, the equivalent of “…Jesus?” in a Sunday School class.

“Then who got the middle school?” you ask? Historians best answer: the bullies.

This book is sort of the ur-text of the modern Educational Traditionalism movement, or at least the part of it that focuses on the science of learning. If you care about teaching, you’ll love it. It hits a very different note than what we do here, but in a helpful way — whereas Egan opens up the doors as to what we can hope for, Willingham exposes many sensible-sounding teaching ideas that fail miserably, and why they do.

Boast, boast, boast…

Those of us who’ve been part of these: care to share?

And if you didn’t: have you considered learning the art of memory?

> This could become a real concern, but, I think, a manageable one.

E.D. Hirsch has opinions on how this could go wrong. He is, of course, an arch-traditionalist. Going off "The schools we need, and why we don't have them" - one of his arguments is that children of itinerant workers who follow jobs around as they come and go can end up changing towns/states, let alone schools, several times a year (Ch. 2.4). Once a school has a reasonable proportion of these kids, and tries to do its best by (correctly) not assuming any background knowledge, the one who does stay in the same school throughout their childhood ends up "made to read Charlotte's Web three times in six grades" (Ch. 2.3, page 29). Hirsch mentions statistics that some NYC inner-city schools have turnover rates of more than 100% in each academic year, that the average Milwaukee school has a 30% yearly student turnover rate etc.

To quote Hirsch on something that could be a literal reply to this post (Ch. 2.4):

"Consider the plight of Jane, who enters second grade in a new school. Her former first-grade teacher deferred all world history to a later grade, but in her new school many first graders have already learnt about ancient Egypt. The new teacher's references to the Nile River, the Pyramids, and hieroglyphics simply mystify Jane, and fail to convey to her the new information that the allusions were meant to impart. Multiply that incomprehension by many others in Jane's new environment, and then multiply those by new comprehension failures which accrue because of the initial failures of uptake, and we begin to see why Jane is not flourishing academically in her new school."

Hirsch's solution of course is One Curriculum To Bind Them All, ideally at the national level - or at least a Common Core taught throughout all schools. One can have separate debates on (1) whether that is a good idea, (2) whether that is a workable idea, and (3) what content should be in such a curriculum, and where.

I am quoting this not necessarily because I agree, but because I think it's on topic and contributes to the debate. I would add personally that Jane's possible struggles to make new friends from scratch and integrate into a new community, as well as the deprivation that might have prompted her parents to move mid-school-year in the first place, would disadvantage her even in the best-designed school system. I don't think there's any really good solution to this problem (and no, "don't teach them anything, just let them discover themselves" doesn't count).

If the question becomes, what is the best we can do under the constraints we're working with, rather than some abstract notion of "goodness", then I do strongly endorse cumulative content though.

I believe I heard you say there are some things that must be learned via some rote or non-narrative means. Would you provide examples and explicate why this is so? Thanks.