1. A problem

The whole point of “helping kids learn things” is that we make changes to brains that stick: that is, that are remembered.

But brains are terrible at this. So much is largely forgotten after a week or a month; only the merest fragments remains after a year.

Worse: as students begin to realize this, studying begins to feel futile.

2. Basic plan

Teach kids the memory techniques that others have figured out over history, and together actually use them, routinely, to secure some of the most important things we learn.

3. What you might see

Kids using the link system to learn the names of their classmates, their teachers and secretaries and lunch ladies and janitors.

Kids creating a major system to memorize their address, their parents’ phone numbers, the number of members of the Electoral College representing their state,1 and the birthdays of all their family members.

Kids using the method of location to store the Five Pillars of Islam, the Ten Commandments of Judaism, the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism, the Seven Deadly Sins of Christianity2, the Four Yogas of Hinduism, and the Five K’s of Sikhism in their heads.

4. Why?

If you squint, the whole of education can be seen as making lasting changes in minds. Without this, we’re just wasting children’s time.

The arts of memory liberate us from the cruel constraints of our biological propensity to forget, forget, forget. They’re a way to inject meaning and joy into the school day.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Tellingly, the “ars memoriae” seem to have been developed at the same time and place as modern analytical thinking — they attended the birth of math, science, philosophy, and history in the Greek city-states in the 500s BCE.3

They were practiced in the ancient world, forgotten in the Dark Ages, and revived in the High Middle Ages, being perfected in the early modern period.

Now, these are mostly ignored; at best we teach about them as cute tricks students can use to study more efficiently on their own.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

What’s interesting here is how all of these are best explained by Egan’s tools.

The method of location (aka “the method of loci” aka “a memory palace”) works by associating hard-to-remember information with a location.

Q: Wait, why does trying to hold MORE stuff make memory EASIER?

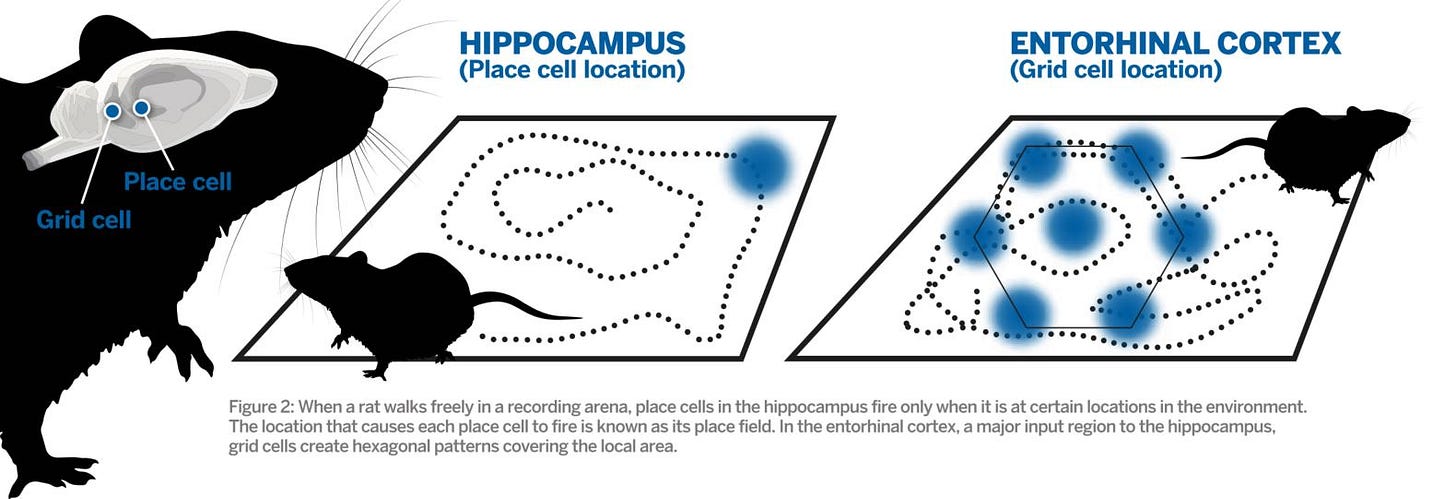

Because 🤸♀️LOCATIONS are special. (What do these weird emoji mean?) The brains of mammals have special areas — “place cells” in the hippocampus and “grid cells” on the bottom left & right of your brain, right behind the eyes.4 We’ve inherited them from our rat-like ancestors because, when you’re scurrying over the ground being chased by a Velociraptor, it’s really, really helpful if you can remember how where the nearest bush, log, or sleeping T-rex is.

Q: What could the look like?

Let’s just take the Buddhism’s Four Noble Truths as an example. The version I learned goes like this:

Understand suffering

Let go of desire

Experience freedom

Cultivate freedom

Now imagine walking into your childhood home. As you enter, you see on the wall (1) a framed photo of a ship on the sea being torn by the waves. In the room, there’s (2) a bundle of sparkly helium balloons tied to a chair, and with a scissors you snip the strings. You walk to the kitchen and see (3) a single sunflower being enlightened by the Sun, and walk through to (4) your garden, when you cultivate sunflowers.

Bam! You’ve got the Four Noble Truths in your head!

A similar principle is probably behind the link system. The link system works by connecting relatively dull information (like names) with relatively insane images. To wit, if you wanted a class to remember that Beatrice manages the office, Franklin mops the floors, and Margaret serves lunch, have them imagine…

Beatrice surrounded by bees

Franklin cleaning with an old kite, tied to one of those keys he’s always carrying… just like BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

Margaret serving Margaritas5

Q: Huh. I can imagine that working — why does it?

For vision-dominant animals like humans, 🤸♀️IMAGES are special. And if you can mash up something (like a hive of bees) where it doesn’t belong (like a school office), you’re adding in 🤸♀️INCONGRUITY.

Truly, all of these — including the major system, which I haven’t talked about (but here’s a video!) most of these depend on sprinkling a little 🤸♀️EMOTIONS and 🤸♀️HUMOR into the day.

6. This might be especially useful for…

Geeks, nerds, dweebs, dorks, and dinks… and also kids whose parents wish their kids were a little more like those first ones.

7. Critical questions

Q: Who cares about facts?

Facts get a bad rap.

We think about facts as dry and dull, and of course they can be. Honestly, the major thrust of Egan education is to point us away from “facts” and toward deeper forms of information — sensations, stories, puzzles, heroes, villains, sweeping metanarratives…

But, look — we can’t live without facts. “What is my email address?” is a fact, as is “what did my barista say the name of her sister who’s fighting cancer was?”

Q: But facts are booooooring.

Yes — and if we understand that, we implicitly recognize why they’re hard to remember, and what it would take to remember them: make them interesting.

When most people study, they ignore this (obvious) insight; instead they try to cram the facts in through dull repetition. Practitioners of the the Art of Memory ask how we could make the facts interesting by dipping them in nonsense.

Q: But isn’t memorizing sheer drudgery?

The whole idea behind the Art of Memory is that it’s the opposite — systematic imagination. Controlled insanity. Weaponized foolishness.

Q: If you use one of these tricks to remember something, will you remember it forever?

Nope — or at least probably not. I understand that people who use one of these to memorize digits of π go to sleep… and then have to work on it again the next day. But to remember something for a long time, you first need to remember it for a short time. This gets you there. (Beyond that, we need a spaced repetition system.)

Q: Isn’t this knowledge without understanding? (In the Buddhist example above, it’s not like we’re all now “enlightened”.)

Yes! But shallow knowledge can be the trellis on which real understanding grows. (Note that the Buddha himself invented many mnemonic devices to help his monks pursue enlightenment!)

Can you think of another way this could go terribly, terribly wrong? Frankly, WE WOULD LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT IT. Become a paid subscriber and join in the comments conversation.

8. Classroom setup

I’m getting over my skis here, but: is there anything we might want to do to make the classroom (or the whole school) a memory palace? (Or would that require making sure that we not change the school?)

9. Who else is doing this?

There are so many people (and groups, like the Memory Institute) who tell people how to do this. And if you haven’t read Joshua Foer’s Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything, it’s a wonderful introduction (and a treat to boot).

But there aren’t, so far as I know, any schools that actually build this into their curriculum. (Anyone know of an exception?)

Update: the always-exciting Edward Nevraumont, who’s coaching his 9-year-old daughter to compete in the National History Bee, has written a very helpful post on how to build a memory palace with your kids:

How might we start doing this now?

These arts have been known for thousands of years, which is my way of saying there are a lot of videos about them on YouTube. Here’s one on the link system; here’s one on the major memory system; here’s one on the method of location.

10. Related patterns

It’s important to not overuse this. But that said, if we could make it easy (and somewhat pleasant) for kids to commit the facts they’ve learned to memory, we can connect this to many of the other patterns and help them fall even more in love with the world.

Most obviously, the Art of Memory° can support the humanities in Geography by Heart° and Historical Dates°. It can also be used in science to collect some of the juiciest facts in Local Birds°, Local Trees°, Local Bugs°, and Local Flowers°, as well as probably everything.

I’m not imagining many ways to connect it to art (no big surprise there?) or math (because it’s an art!). But in language, there’s so many ways it could be used — to more easily learn A Poem a Week°, learn Many Subtle Words°, or the grammar rules of a Foreign Language°.

Afterword: Going full-meta, here

Anyone in our readership do this with their kids? If so, would you be up for having a conversation with me about how we might start on this now?

In other news, t’night I’m having a SECRET CONVERSATION about Egan with someone famous. I’d tell you about it, except, y’know, secret. (He doesn’t even know, yet.) We’ll see if it goes anywhere; wish me luck…

Note to non-American readers: this is confusing, and probably won’t ever be very important. Go ahead and forget you read this.

Protestant readers: yes, these belong to you, too.

The counterargument to this is that they go back even earlier. From how I (a know-nothing armchair historian) understand the evidence, it looks like the techniques that oral societies use — like song, story, metaphor, and imagery — are even more important, and get baked into what we’re doing through all of Egan’s MYTHIC (🧙♂️) tools. Which, just to reiterate, are more powerful than this pattern! But this is useful for some different things.

If I was trying to capture that “science journalist suaveness”, I would of just written “it’s in your entorhinal cortices, idiot”, and left it at that.

Okay, this is probably how I’m likely to remember Margaret’s name.

Years ago, my Latin teacher made the whole class memorise the first 10 lines or so of the Aeneid. What made it a lot easier, apart from images and story, is that it's also a form of poetry with a distinct rhythm (in this case a hexameter) - the stresses on the first line for example are "*arma vir*umque can*o troi*ae qui pr*imus ab *oris". I have a hunch that there's a somatic trick using 🤸♀️RHYTHM - tapped out loud if need be - to help with memory too, that's probably also biologically special in a way. After all, that was also a part of many cultures' storytelling techniques.