1. A problem

Our knowledge of the world is shallow, because schools have stopped teaching history. This was a clever solution to a problem that didn’t exist.

A century ago, educational psychologists concluded that children were incapable of understanding anything they hadn’t experienced themselves. To fix this, they yanked a careful coverage of history out of elementary school; in its place they plopped a new “expanding horizons” model of social studies.

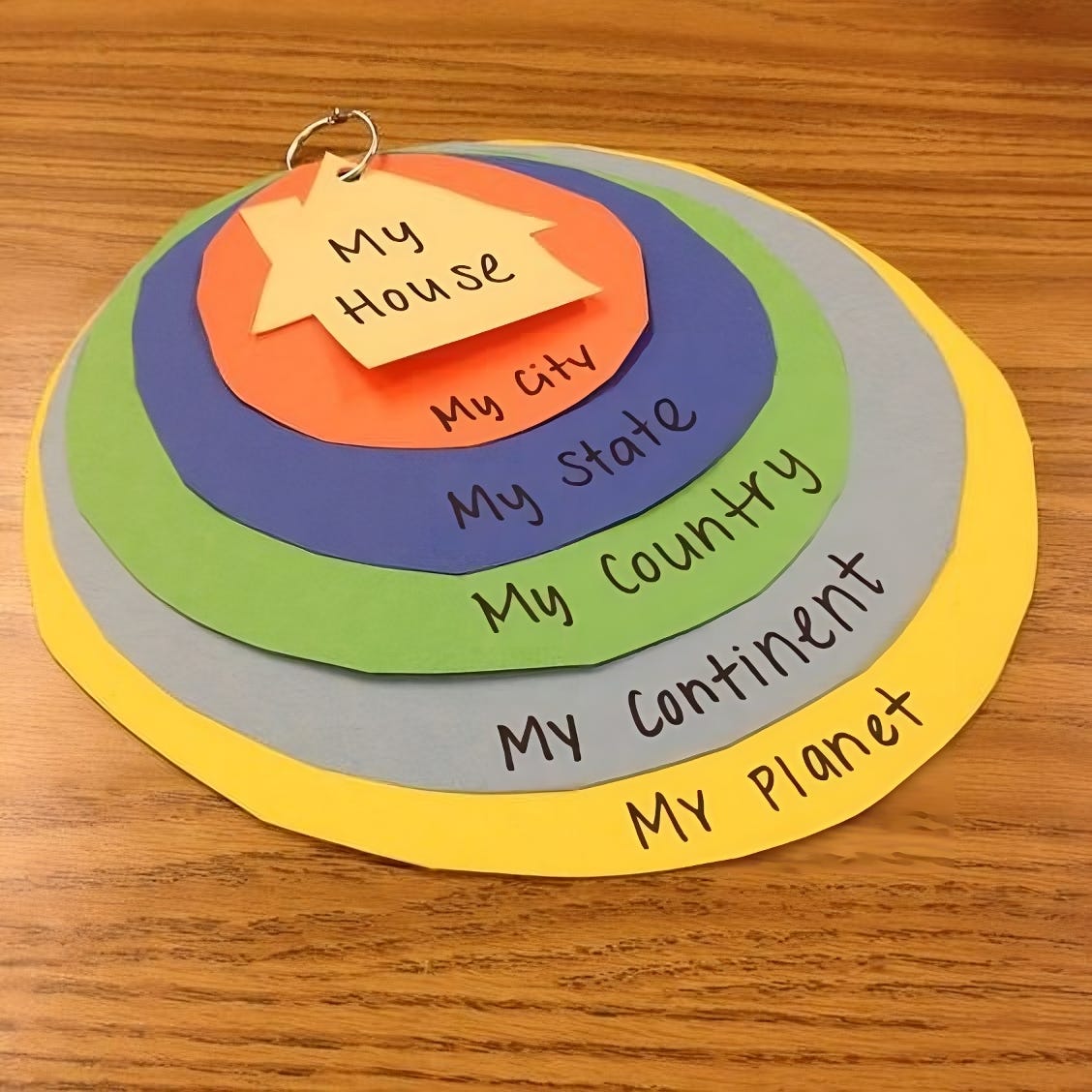

Details vary, but in many countries, the focus of social studies in the early years goes something like this:

kindergarten: themselves

grade 1: their families

grade 2: their neighborhood

grade 3: their city

grade 4: their state

grade 5: their country

grade 6: the contemporary world1

By the time kids get to middle school, it feels unprofessional to tell them stories, so teachers often jump to analyzing abstract historical processes — something that is very hard when students don’t know anything about the history they’re supposed to be analyzing!2

Because of this, the epic stories of history have no home in the contemporary curriculum — even though that’s the part of history that’s easiest to learn, and most beloved.

2. Basic plan

In Egan classrooms from grades 1 through 8, teachers tells stories from history to the class — ones that are both true and captivating.

In elementary school, these stories can be short, taking just one or two class periods to complete. In middle school, these stories get more complex, taking two, three, or four days tell. Each day ends on a cliffhanger, and begins by recapping what happened before.

3. What you might see

Imagine walking into an elementary school classroom, and finding the lights off, and the students sitting in a circle, raptly watching the teacher spin a tale of a struggle against oppression, or against ignorance, or against despair.

From my ACX book review of The Educated Mind —

we can tell kids the stories of the war of the Greek city-states against the Persian empire, and the slave uprising of Spartacus against the Romans. We can tell them about the plight of Jews in medieval Europe, and of the unsuccessful Sepoy Rebellion in India against the British. We can tell the stories of the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions, and about the Chinese Taiping Rebellion against the Qing Dynasty. We can tell them the story of the escaped slave Harriet Tubman returning to the South to rescue her kinsmen, the story of six-year-old Ruby Bridges facing threats to integrate her elementary school, and the story of how the Mau-Mau uprising led to modern-day Kenya. We can tell the stories of Mexican-American union organizer Cesar Chavez and of Malala Yousafzai surviving an assassination attempt to advocate for female literacy.

This is just a tiny sample of tales we might include. The world does not lack for stories that can capture the attention of elementary schoolers.

Imagine walking into a middle school classroom, and seeing much the same — but followed by long conversations of who in the story was the real hero, and what we might have done in their situation, and how this might have effected the other stories we’ve talked about.

“BUT WHAT ABOUT TAYLOR SWIFT’S EPIC BATTLE AGAINST HER RECORD LABEL???” you’re asking. Commenting on these weekly pattern language posts is a perk for paid subscribers, but you can become one for just $5/month, and engage in all the Swift-related religious wars you’d like.

4. Why?

The “Expanding Horizons” model is a recipe for narcissistic, xenophobic, and thankless adults:

By making the self the center of the world, it seems like it helps shape people who… well, see themselves as the center of the world.

By only slowly moving away from the sorts of people who are close to them (people in their family, their community, their city, their state, and their nation), it leads students to assume how they do things is normal, and other people’s ways are odd.3

The good things around us came from people who fought to improve the world. By holding off on talking about these, it limits students’ ability to be thankful for how much life has been improved.

And since really understand anything requires understanding where it came from, the “Expanding Horizons” model cuts away the historical context that makes it easy to make sense of origin stories.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

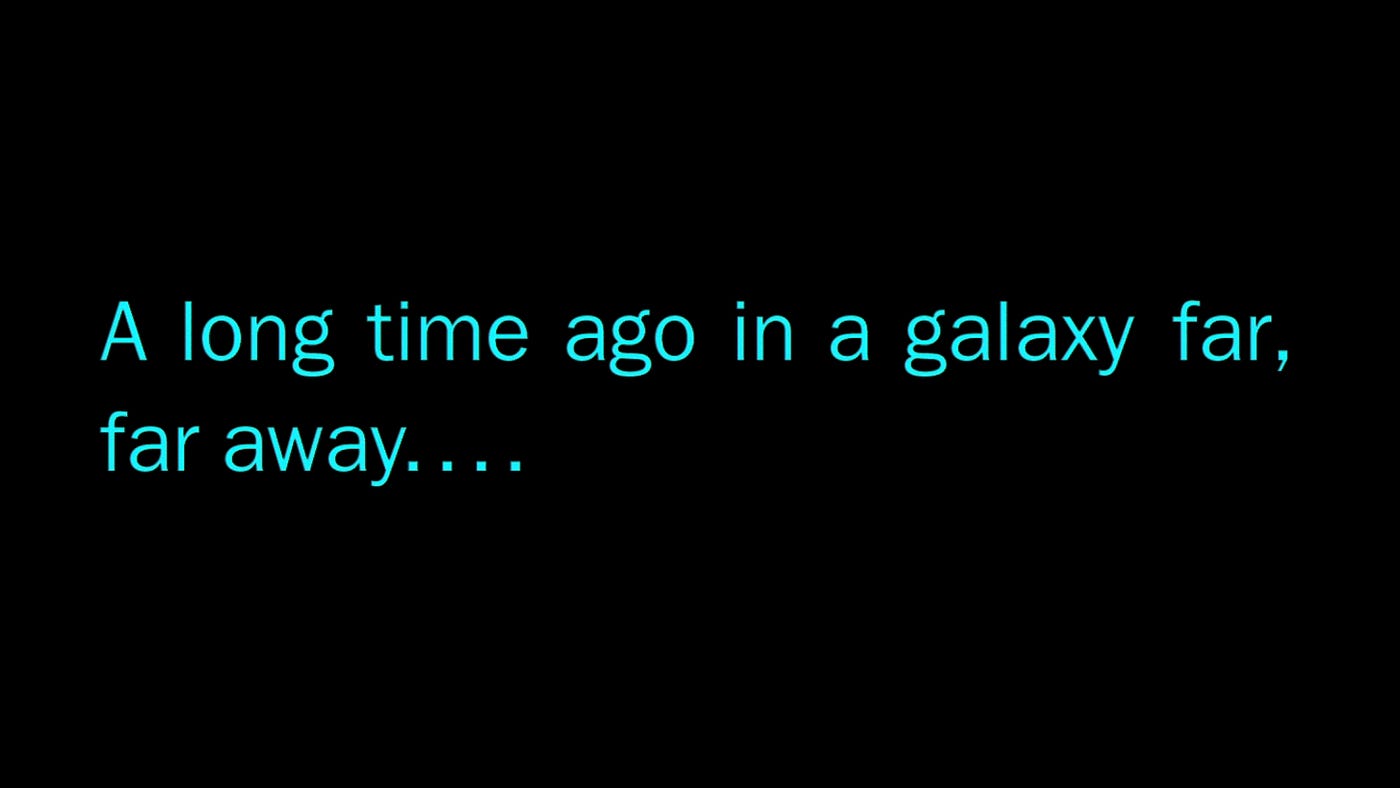

Look, it’s not like there’s actually an intellectual foundation for the “Expanding Horizons” model. The problem it was originally trying to solve was that children couldn’t understand anything they hadn’t experienced themselves. This is obviously bunk to anyone who’s seen a child enraptured by a story that begins

How did George Lucas make five billion dollars doing something that educational psychologists said couldn’t be done? By telling an epic story.

All thick cultures tell epic stories of the people in their past. To tell these stories is to say “this is who we are”. Epic stories create a sense of belonging. And we want help students see that they belong to all humanity.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

Weekly reminder: At the heart of Egan’s understanding of education is the notion that, for humans, certain practices and formats of information are special. Egan calls them “tools”, because throughout history, cultures have used them to pass themselves down. He groups them into five “toolkits” — SOMATIC (🤸♀️), MYTHIC (🧙♂️), ROMANTIC (🦹♂️), PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬), and IRONIC (😏).

Well.

Obviously, telling epic narratives requires 🧙♂️STORY, and good stories involve 🧙♂️EMOTIONAL BINARIES and 🧙♂️VIVID MENTAL IMAGES.

As kids get older, these stories can help them 🦹♂️ASSOCIATE WITH THE HEROIC; useful for teens who’d otherwise be mimicking whatever vapid-influencer-of-the-week that an algorithm shoves at them. Carefully talking about these epic characters (good, bad, and in between) prompt feeling out which 🦹♂️ IDEALS they want to organize their own lives around.

But ultimately, we want to move beyond stories: in high school, history will revolve around 👩🔬PROCESSES RATHER THAN HIGHLIGHTS — trying to figure out how the world really works. Students will be able to understand those proposed processes (think “dialectical materialism”, “the moral arc of the universe”, “the patriarchy”, and “life is one damned thing after another”) only insofar as they already know the details that these try to connect. More: students will be hungry to see the big picture only if they see that 🧙♂️STORY is too weak to explain the world.

And eventually, as they see that all people are creatures of their time, they’ll come to realize that, well, they are, too! They don’t stand apart from history, but are a part of it. They’ll move 👩🔬FROM TRANSCENDENT PLAYERS TO HISTORICAL AGENTS.

As they see the tale of different people and events told from radically different vantage points, they’ll come to see that having a final judgment on a person is incredibly difficult, and will begin to 😏APPRECIATE AMBIGUITY.

The biggest gain from all of this, though, may be SOMATIC — they’ll feel 🤸♀️ATTACHMENT toward the whole swath of humanity, and not just the people who most resemble themselves.

6. This might be especially useful for…

People with lower-than-average skills in a few random cognitive abilities

We’ve created schools that prize cognitive abilities that are rather rare — among them analytical skills, the ability to focus on material that’s rather dull, and perseverance toward long-term abstract goals.

But people in general are agog for stories. And stories can convey so much understanding.

Defining “success” as having the skills possessed by only a few while ignoring stories is not how most past societies structured themselves. It seems unfair, inequitable, and (dare I say) grotesque. It also seems like a poor strategy for getting all minds on deck to help the society thrive.

This is all to say that I think that this would be particularly good for students who are near (or somewhat below) the center of the bell curve in analytical reasoning, sustained attention, and grit.

Story geniuses

That said, there really are some kids who are just geniuses at crafting narratives. Hearing all these stories will develop in them a storehouse of stories that they’ll draw on for the rest of their lives.

7. How could this go wrong?

We make the stories boring

If our teachers suck at telling stories, this is a waste of time. (So how can we help our teachers get great at storytelling?)

We make the stories sugary

Egan wrote “Disney-esque sentimentality is the exact emotional equivalent to intellectual contempt”; our stories shouldn’t avoid discussion of difficult things. They shouldn’t all show evil being punished and good being rewarded. They shouldn’t all have happy endings!

Obviously, we should take the students’ capacities for darkness (and their parents’ willingness to put up with the occasional nightmare) seriously; the goal isn’t to push a Frank-Miller-does-Batman anti-hero worldview on kids.

But the norm is to go in the opposite direction, and deny the human experience. We should navigate this well.

We choose the stories poorly

Say, if they all end up being about Western Europe — or if none of them end up being about Western Europe!

We turn these into another stupid worksheet

Egan imagined what would happen if movie theaters were run by schools: as soon as you blinkingly step into the lobby, you’re accosted by evaluators wielding clipboards:

“What was the color of the protagonist’s car?”

“What themes were presaged in the opening scene??”

“What was the name of her dog???”

…then your salary is raised or lowered depending on how accurate your answers are.

We, ah, shouldn’t do that.

The teachers burn out

It’s hard to tell a good and accurate story! If their stories are great, and the teachers burn out, we lose. We have to make it easy to tell these stories well. This is something we should eventually put resources into.

You there! Yes you, the curmudgeon! I bet YOU can think of another way this could all go south. Become a paid subscriber and help save education join in the comments conversation!

8. Classroom setup

On first look, a traditional classroom might seem made for storytelling: chairs and desks point students toward one adult, standing at the front.

On second look, we can do better. School chairs are only mildly comfortable, at best; the fluorescent lights in many classroom ceilings work to disenchant.

Even beyond that, it would be good to carefully separate the experiences of doing work and listening to a story. What we want to create, of course, is the experience of sitting around a campfire.

Something like this can be done for cheap: the lights can be turned off, carpet squares can be donated, and a YouTube video of a fire can be shown on a screen or projected on the wall.

9. Similar stuff (others are doing)

This is ground that classical education has been exploring for some time. I first fell in love with homeschooling through Susan Wise Bauer’s The Well-Trained Mind (thick, but quite skimmable, and your library has it); much of what they’ve done we can borrow, and improve on.4

It’s also, I’ve only lately realized, something that Waldorf schools have put work into.

(If you, dear reader, have any first-hand experience with either of these, and would be willing to tell us in the comments, ping me at Science is WEIRD; I’ll gift you a week’s paid subscription.)

10. Open questions

How can we make this easy for teachers?

How can we choose stories, do research, and write notes for this — so individual teachers don’t have to? And how can we do that without turning this into a script for teachers to read? (That would be its own form of awful.) Could we hire historically-knowledgable storytellers to record videos of them telling stories that teachers can emulate?

Which stories?

“Which history?” obviously, carries political charge. Happily, we have wiggle room: since there’s little history happening in elementary schools at present, there’s not much existing history to be fought over. It’s pretty easy to add things in without making any perspective feel like they’re losing anything.

But we shouldn’t ignore the epic political battles that have been waged over history curriculums in the past. We can take advantage, here, of the fact that Egan has something new to offer to both sides of “the history wars”.5

11. How could this be done small, now?

Can I get your critique?

Years ago, when Kristin and I were running a weekend gifted/talented program out of our Seattle apartment, we began to craft these. Oof were they fun. Looking through our records, I find we told the stories of

Queen Hatshepsut

Hammurabi

Sargon of Akkad

Vardhamana (aka Mahavira)6

Confucius

Lao Tzu

Abraham

King David

Cyrus the Great, and

Socrates

Alas, all of those are lost to time! I have found, however, that I recorded a draft of the multi-part story of the Buddha. If you’d like to look at it and give critique, feel free! (Please excuse the recording quality; I was so young then, as were we all.)

12. Related patterns

Though the scope of Big History° is bigger than a traditional “world history” (heck, it goes back to the Big Bang), it most assuredly includes world history’s scope. Thus, we should draw these Epic Stories° from as diverse an array of cultures as we’re able.

Many of these stories will be of people who thought, believed, worshiped, and acted very differently than us. This is a good way to put Radical Inclusivity° at the core of our ethos.

These stories provide excellent fodder for Philosophy Everywhere° conversations — especially about ethics. And not only do they provide some good illustrations of whatever an individual school’s Named Virtues° happen to be, but they provide great opportunities to talk about (and perhaps even interrogate) those virtues.

Spiral History° means that many stories encountered in elementary school will be revisited (and reconsidered) in middle school. And each story can be placed on one of our Timelines°, so students can understand how they work together.

Once students hear a story, they can make it their own by taking on Playing inside Stories° challenges. To help with this, we can teach them Simple Story Recipes° so they understand how compelling stories work.

Finally, these help us paint a picture of the past that will help give flavor to Origin Stories°.

Afterword: Going full-meta, here

Do you get the idea that Egan thought elementary social studies was modern schooling’s original sin? I do. But he also thought that the practice it replaced — boring memorization of names and dates — was self-evidently terrible. His solution — a rich curriculum of epic stories — is a third way. It also provides the engine for so much of what follows.

In other news, I’ve lately been giving a lot of my time to considering how fast I want to get these patterns out. I’ve realized that their power lies in their quantity and connection, rather than their stand-alone individual depth (which I can shoot for in other essays). They’re bougainvillea, rather than sunflowers:

Once again, I tried to make this shorter, and once again, I failed. I have a new idea I’m working on to pump them out faster and connect them… look for that soon.

Anyhoo, if you know of someone (or a community) who’d get very excited about this idea (whether or not they’d like to subscribe to the rest of the newsletter), please do share!

Just to head off suspicions that I’m making this up, I’m pulling this specific list from Walter Parker’s 1991 Renewing the Social Studies Curriculum, and Walter didn’t cite it to be critical. Even so, he was a fantastic professor and a strong intellect, and I was fortunate enough to have him on my master’s committee.

More than once I had a history teacher open the year with “I know that in the past you’ve just been made to memorize names and dates, but in this class we’ll focus on the big picture!” …and then go on to have us memorize names and dates, because you actually need details to make sense of the big picture, and we had never actually been made to memorize names or dates.

Spoiler: nothing about the modern world is normal! Westerners are the true WEIRDos.

Stay tuned for future patterns as to how we can. Oh, we’ve no lack of plans here…

“And what would that be?” you reasonably ask. I’m working on another pattern, tentatively titled something like “Beyond the Culture Wars”. Paid subscribers can expect a spicy draft of it Someday; everyone else can expect a mature and cleaned up version Someday After That.

And if you don’t know who Mahavira is, you’re in for a treat.

Hi hi! Haven’t commented since that first comment (exams, what are you gonna do), but happily paid to subscribe!

I love this. My friends and I loved reading those kiddie biographies for this very reason (if you’re in the US you might have seen them, the Who Was…? series). I learned more history from those and the American Girl Doll books in the library than I ever did from a textbook in middle school. Little Golden Books has also expanded into child-friendly biographies; I saw Rita Moreno, Ronald Reagan, and King Charles III at my local bookstore last month.

The only thing that troubles me takes me back to the binaries. Your Buddha video was fantastic, and I loved how you focused on “pain/pleasure.” I know you might be able to fix this with diversity of stories and with well-informed teachers, but as kids are forming a self-concept they glom onto what makes them them. The villains in complex historical stories might get unconsciously flattened down to one-dimensional bad guys, perhaps sowing the seeds of bias. The heroes, who in real history might have been complicated, might get unconsciously inflated.

I don’t think I’m explaining myself very well, so let me use an anecdote. I used to tutor in an area that was heavily populated by members of a specific ethnic group I am not a a part of. The school curriculum required that I help the kids understand the unacknowledged genocide of this ethnic group through stories and worksheets on its anniversary. This political situation is very real, very active, and very scary, with a relevant impact on many relatives of the students. I took this approach at first, but soon realized the students, even the ones not a part of the group, had taken it and run with it too far.

People who were not like them? Compared to members of the oppressive ethnic group. People who had mildly annoyed them? Compared to members of the oppressive ethnic group. It became shorthand for anyone who didn’t fit or wasn’t good or heroic. It seemed that they genuinely began to dehumanize members of the other group, and dehumanizing anyone is an absolute no for me for any of my students. This went away immediately the next year, when we went in on names and dates instead.

I don’t think that there’s anything wrong with teaching history as a story. I just think that stories are good places for children to play and explore wild natural binaries and identify with goodness and heroism and understand how we got to where we are. I just think we have to be careful when situations are active and close to home— and we never quite know what those are for any particular group. Our tendency to Disnefy must be kept firmly in check. Many of those Little Golden biographies feel quite obviously sanitized; making difficult stuff appropriate for younger ages without talking down is harder than you would expect for the average person and I imagine the newer Egan-trained teacher. (See the bio of King Charles III: he and Diana split because he liked the country and she liked the city.) It’s a fine line to walk sometimes between appropriate and intellectually honest. Names and dates give sterility and clinical distance, in a way.

Thank you so much for this post and it’s an honor to subscribe!

On the topic of storytelling, Brandon, are you by chance familiar with Michael Dorer's book, The Deep Well of Time? The stories in his book are the most beautiful renditions of the Montessori Great Lessons that I've heard thus far. They are SO carefully and beautifully crafted and just so, so good and just full of wonder.

In writing these stories Dorer also borrowed some techniques/approaches that Jerome Berryman incorporated into his Godly Play stories. In my experiences as a Godly Play storyteller I've found that in order for me to properly tell one of these stories, I have to be able to tell it by heart, and "by heart" I don't mean memorized. I need to know it so well that it has also become my story to share. To do that, even though the stories are short, I still used to spend hours over the course of a week practicing the one story I was presenting that week to make sure I was happy with the timing, inflection of my voice, how/where/when I moved the story materials, etc. Some of the shortest story scripts required the most preparation because every word, every action, every pause was that much more significant. Often times it was a story I already knew (spiral curriculum) so I just needed to refresh/revisit but that still took time to get it just right. And I wonder how many teachers could/would carve out this kind of time on a regular basis without taking something else out. Or maybe that's what's needed?

I think there's also an art to excellent storytelling, so we'd want to add storytelling training in teacher education to really see the full benefit. If it were added to the curriculum, I wonder what teachers would think? Would they find it more generally helpful? For me this training has been helpful in a wide variety of settings -- I've leveraged it in a wide variety of "meaning making" opportunities, ranging from how I retell childhood stories to my kids, how I have facilitated Equine Facilitated Learning sessions, all the way to how I've framed a fundraising campaign for my kids school.

I think there's a lot here to explore around storytelling, this is just some quick popcorn thoughts. I'm curious to read what others share!