1. A problem

Sometimes a story hits you, pierces you deep, and changes you. Sometimes a story immediately finds its home in your mind and never leaves. Compared to the other tools we use to teach — facts, definitions, concepts — stories are powerful.

But often, we skate over a story’s surface. We find it interesting, but then never come back to it.

The way to re-humanize our education, Egan argues, is to make the backbone of the curriculum the greatest stories of the world. But it seems there’s a chance we could do this, and still have little that changes kids.

2. Basic plan

Repeat the key stories — the ones at the centers of important lessons — but do something new with them each time. Treat every story as a jungle gym: something to play inside of, to experience in ever-new ways.

After telling an important story to the class once, tell it again, but pick kids to act out scenes with props. And after that, invite students (as a class, individually, or in pairs) to go even deeper into the story through a set of challenges.

3. What you might see

Re-enacting

A teacher retelling a story, and members of the class hamfistedly acting parts of it out with a Spider-Man mask, a string, and a large pot1

Simple summaries

A kid re-telling the story to another in just one sentence, then in just two sentences, then in just three

A kid summarizing the whole story in just three or four words

Dissecting

A student listing out all the characters, and what they want

A student filling out a sheet of how the main character attempts to get what they want, how that fails, and how they try again

Switch the media

A kid acting the story out with Lego figures

A kid drawing a single scene of the story on paper

A kid turning the story into lyrics that go with the tune of a song the class has learned

A kid turning the story into a poem that emulates the style of another the class has learned

Point of view

A student re-telling the story from another character’s perspective

Characters

A student recasting the story with animals

A student doing an ad hoc psychological study on the main character

A student swapping out the main character with another character from a different story

Setting

A kid setting the story in a very different time or place — ancient Greece, or a middle school lunchroom, or Narnia

Plot

A kid writing a very different ending for the story

A kid changing one detail near the beginning of the story, and re-telling it to trace out how a small difference can change everything

Genre

A student looking at a booklet listing genre conventions, and trying to identify the story’s genre

A student tweaking the story to turn it into a different genre — a murder-mystery, a fantasy-adventure, a sci-fi apocalypse…

Theme

A kid identifying the story’s emotional binary (e.g. greed/generosity) and re-telling it to emphasize a somewhat different binary (e.g. frustration/acceptance)

A kid retelling it with a randomly-chosen binary (e.g. hate/love or slavery/freedom)

Obviously, some of these are more advanced than others. The most advanced might be a full transition into an advanced story-writing course: to re-plot the story as a movie using Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat beatsheet (here’s a summary), or to re-plot it as a novel, using Shawn Coyne’s Story Grid methodology.

4. Why?

Stories aren’t just stories: they’re tiny worlds to explore, to play in. But play requires repetition.

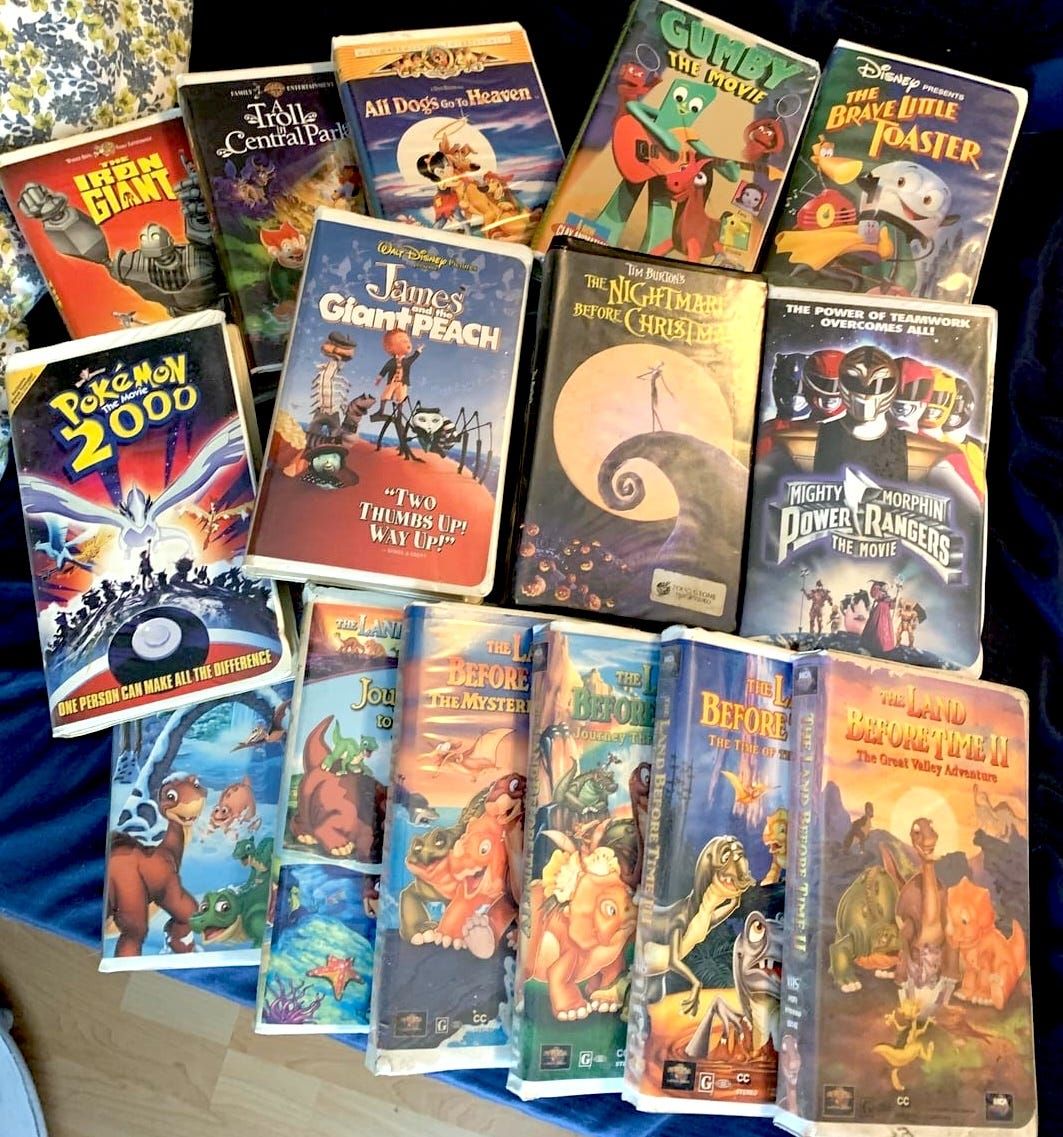

Even today, you can see this in how kids seem to naturally engage stories — watching them over and over2 and physically acting out scenes.

I say “today”, but one of the things that troubles me as a parent is how the technology of TV streaming and movies-on-demand has changed this. Back in The Good Old Days™, most of us only had an armful of VHS tapes of (I can admit it, can you?) frequently crappy movies.

There was something imaginatively useful about this. The restricted quantity led a lot of us to re-watch the same films until our parents despaired.3 And yet it got us to go deep! I fear our kids have a more shallow engagement with their crappy movies than we did with ours.

Rant over (don’t worry).

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

In the modern age, we might think of a story as something set in stone — or, more literally, set in ink or film. There’s an “official” version of a story, of which variants are imperfect replicas.

Now, increasingly we blur the edges of this — we talk about “the director’s cut” of a movie, and recognize the “fan fiction” that grows up around an especially exciting book or TV show. We might be surprised, though, to realize that the entire question of what’s “canon” is quite recent.4 For the vast span of human history, versions of a story proliferated, because —

we never tell the same story twice.

That’s not to say that communities don’t police how their stories are told: all do. Stories are culture, and culture is identity. This is why almost every traditional culture makes “storyteller” a Very Important Person, and only allows a person to become one after many years of mentorship. (Among the Mandinka of Western Africa, one begins studying around the age of three, memorizing vast quantities of information under an accomplished master, and practicing public performances.)

But all this care is needed precisely because —

no, seriously, we never tell the same story twice!

Pick any traditional story — folklorists have catalogued multiple versions of it. Some of this is because communities splinter, and small differences in telling add up over time.

But more importantly for us, it’s because it’s bad if you tell a story exactly the same way each time! To tell a story is to communicate a message, and that message will vary if you emphasize one small detail over another. (Not for nothing were storytellers often advisors to rulers.)

This is all to say that throughout the human experience, a story wasn’t just a bunch of information you hear — it’s a tool you use to thrive.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

Think of this pattern as our foundry for building mastery at 🧙♂️STORY (what do these weird emoji mean?). In doing so, it leans on some SOMATIC (🤸♀️) tools — among them adopting an attitude of 🤸♀️PLAYFULNESS, representing specific 🤸♀️IMAGES from a story, and coming to better understand the 🤸♀️PERSONS who drive the plot.

But it also treats each story as an instance of some more general form — thus tapping into PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) understanding’s 👩🔬CRAVING FOR GENERALITY. When we get kids to think about a story as an instance of a particular genre (or as an instance of “story”), we’re getting them to think big-picture.

And of course when kids try to do that, they’ll realize that these forms don’t work perfectly — that trying to smoosh a particular story into the “mystery” or “sci-fi” or “action-adventure” box forces us to ignore certain parts of it. As the statistician George Box famously quipped, “all models are wrong; some models are useful”. This seems a good way to prompt that IRONIC (😏) realization.

6. This might be especially useful for…

Future aspirants for the Booker Prize Short List, but also everyone who wants to become a “natural” storyteller and communicate important things to other people, which is to say… everyone?

7. Critical questions

Q: You’re saying that we forget stories — but aren’t stories cognitively privileged?

Very much so. And compared to a fact, a term, or a concept, a good story is much more likely to be remembered years later, even if it’s told only once. But “much more likely” doesn’t mean “likely” — remember5 that almost everything we hear once is forgotten. So we want to build repetition into our story-telling methods.

Q: How many times should we tell a story?

Our key stories — the ones that are the centers of lessons — should be experienced at least twice, and as much as a dozen times. If that seems like a lot, compare how often a Normal Human Being (that is, someone born before the invention of smart phones, anesthetic, or the alphabet) might have heard one of the important stories of her culture.

Let’s do a Fermi estimate. Assume an average Norse woman heard the story of the creation of the world (out of the body of the frost giant Ymir, who was licked out of the ice by a cow!) once every other month or so. Assume, too, that she was a particularly squirrely child, and didn’t pay much attention before age five.

By the time she was 15, she might have heard it sixty times (six tellings a year times ten years). Compared to that, even a dozen is small potatoes.

Q: You gave a lot of challenges. Do you have any others in mind?

I’m positive that the ones I gave aren’t the best ones that could be given. We should evolve more — I’m especially thinking ones that lean more into SOMATIC understanding to fall in love with a story like we help kids fall in love with visual art.

Do you have a wider perspective on this? Or can you think of some way this could go terribly wrong, and we could all curse the day this was published? Frankly, WE WOULD LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT IT. Become a paid subscriber and join in the comments conversation.

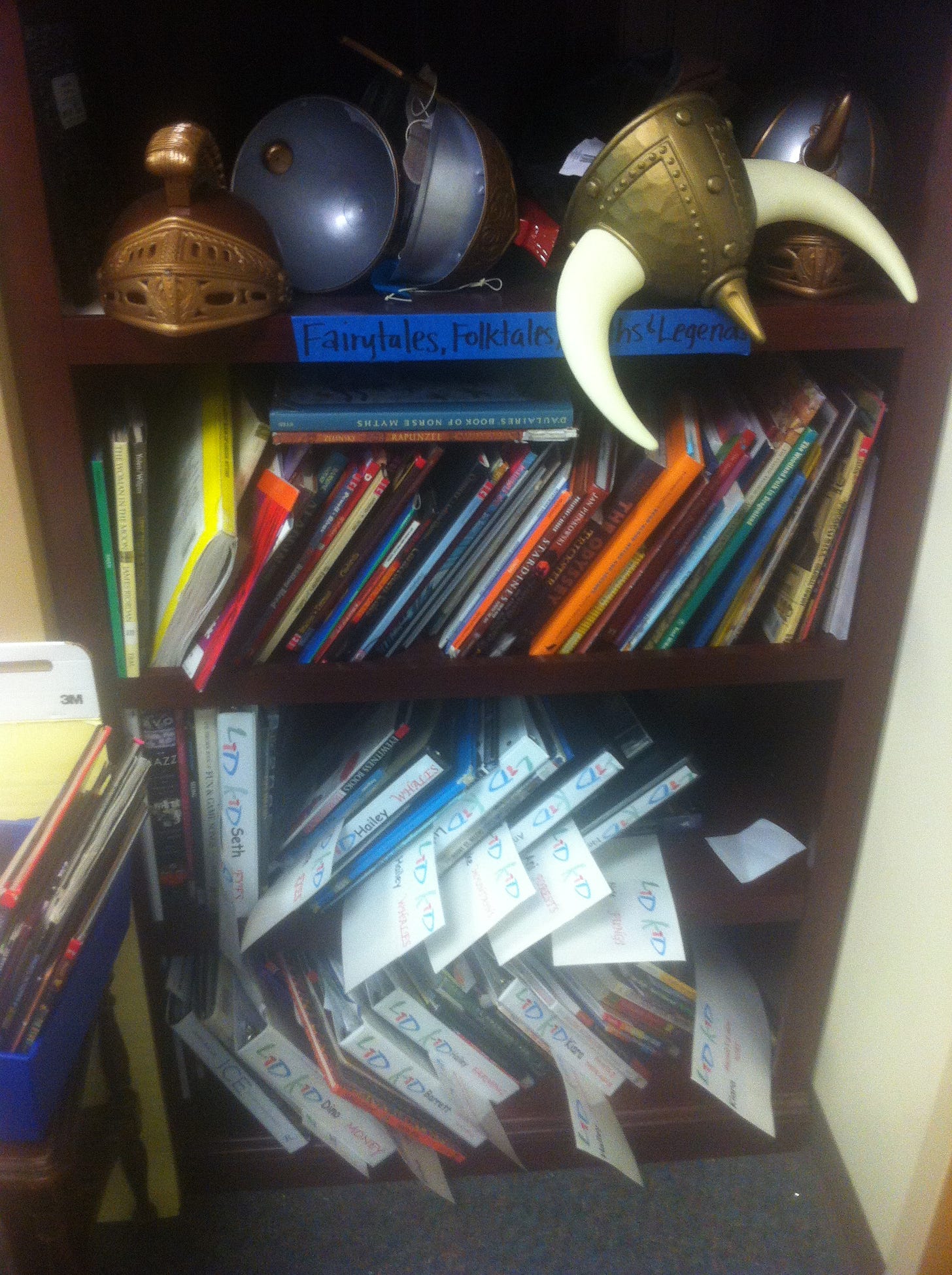

8. Classroom setup

We’ll need props for acting! Hats, crowns, helmets, capes and cloaks, animal masks, scarves and bandanas, foam swords and plastic shields, glass jewels, scrolls, ropes, and cardboard boxes, for starters. None of this costs much money — they’re the sorts of things that can be picked up at a local Walmart at a moment’s notice.6

This might also require a challenge station, and some way of presenting students with the options they’ve already learned for how to go deeper into the story.

9. Who else is doing this?

I was inspired in this by my visit to the elementary program in the Corbett Charter School in Oregon — which was for a glorious moment a place where Egan Education was in full swing. Classrooms had foam swords, plastic shields, and other common props you might buy at a toy store or a Halloween costume place.

The idea of a “challenge station” is taken, though, from Montessori schools.

How might we start small, now?

T’morrow, I’ll post a specific story, and examples of what the challenges might look like with it — and challenge everyone else to do the same with a different story.

10. Related patterns

The key stories are those of Epic Stories° in the humanities, Origin Stories° in math and science, and both World Fables° and A Movie a Month° in literature.

Dissecting these leans hard on Story Ingredients° — didn’t I say that would be useful? It makes a new use of both A Song a Week° and A Poem a Week° (July 3). And in playing with something that other people assume is set in stone, there’s an intriguing parallel between this and an upcoming pattern in math: Every Game is Calvinball°.

In treating a story as something that can be played with for years, it assumes Cumulative Content°. And speaking of multi-year processes, improving this pattern — coming up with better challenges for kids — is just one way we’d benefit from A Market for Lessons°.

Afterword:

The careful reader might notice that I missed a pattern last week. Darn! Drat! It’s ended up being a spicy post to write — which means I need to do it carefully.

I’m on it, though. Look forward to it.

Can you guess what piece of folklore I’m thinking of?

And if you’re like my sister and me and the story is Free Willy, over and over and OVER.

Do you remember the part in Free Willy where the greedy owner of the park asks Jesse whether a public show with the whale would take a lot of money, and Jesse responds “Do dogs pee on brick walls?”, and you laughed so hard?

It got its start, as quite a bit of Philosophic understanding did, with a boost from religion: the word “canon” itself comes from “cane”, e.g. “ruler” — it was created to talk about what books are really part of the Bible, and can serve as straight edges for what people believe.

(if you can)

Pro-tip: the cardboard boxes actually come free with the other things.

Re: Pick any traditional story — folklorists have catalogued multiple versions of it.

For anyone interested, here's an article on the hairy history of attempts to catalog Indo-European tales:

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/aarne-thompson-uther-tale-type-index-fables-fairy-tales

Growing up, this site was my go-to resource for maxing out my library card with as many retellings as possible:

https://surlalunefairytales.com/

- The Annotated Tales section includes subsections on Modern Interpretations and a Book Gallery for each tale.

- The database project a great resource for locating tales from all over the world by their source book title or tale title

Multi-Lingual Folk Tale Database

http://www.mftd.org/

On this site, you can read popular folk tales from all over this world, in their original or a translation.

Re: fall in love with a story like we help kids fall in love with visual art.

Sometimes after reading a great story it can take an hour or two for me transition from "living" in the story back to the "real world". Several of my kids have the same tendency to hyperfocus, so I know that if they read/hear a great book or watch a movie, there is going to be energetic themed play afterwards and to plan accordingly!

Luc Travers's "Touching the Art" book brought up the concept of art as a talisman and I think stories can be used the same way. As inspired, one could take on the persona of a character in a story and channel their strength to help deal with real-life situations. I'm having a hard time of thinking of specific examples, but I've also used stories to get me into the mood to work on things so that it's easier to focus on what may not normally hold my attention as well.