Note: there’s a link to an open house happening this afternoon at the end of this post.

1. A problem

Three times come naturally to us: “now”, “before now”, and “when we all have jetpacks”. That is, we experience time as focused on us, and lump everything that’s not present together.

This is stupid — what we call “the past” contains multitudes of times. Cavemen didn’t fight dinosaurs, nor did Abraham Lincoln.1 Understanding the world requires understanding how these things actually relate to each other.

2. Basic plan

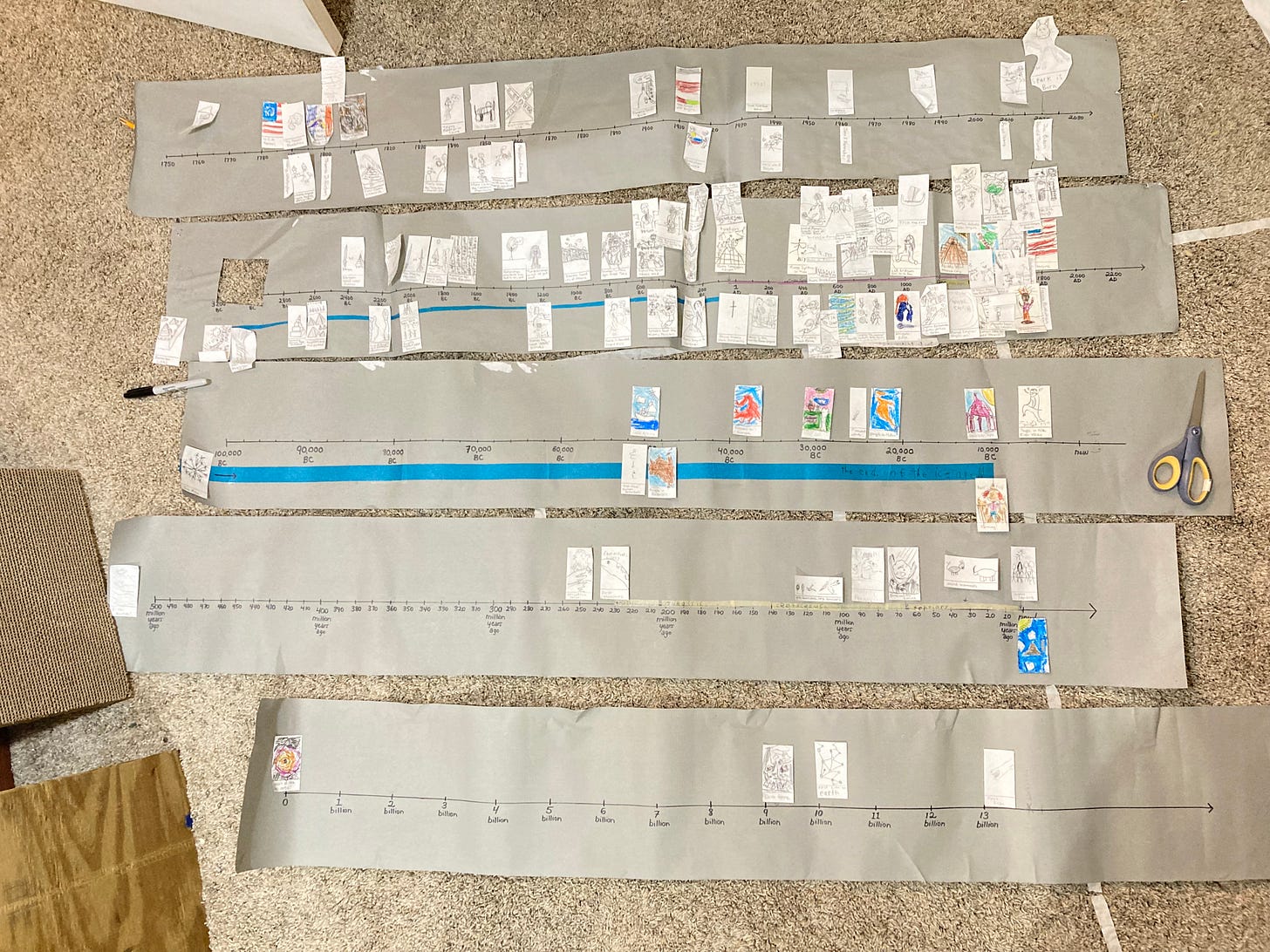

Put up timelines on the wall. First, create different timelines:

modern life: 1 foot ≈ 100 years

civilization: 1 foot ≈ 1,000 years

life: 1 foot ≈ 100 million years

universe: 1 foot ≈ 1 billion years

Use your own numbers to fit your space. Make these as long as possible, and ideally plop each on top of the others. Shade one to show where it fits on the the last (see the picture below for an example). And continue each timeline a little bit forward into the future.

Then plot events as you learn about them in every subject! And put them in as simple images.

3. What you might see

Classrooms plastered with key events like “the first stars” and “the extinction of the dinosaurs”, “Newton discovers gravity”, and “Manutius invents the semicolon”.

Kids pacing along the timelines, furrowing their brows when they see that “the dawn of agriculture” looks so long ago on one timeline, and so recent on another.

Groups kibbitzing about whether we’ll get personal jetpacks in the next hundred, thousand, or million years.

Why?

As many of us who’ve created timelines have discovered, a single timeline is never enough! If you squeeze all the history back to the Big Bang onto a single timeline, all the recent events get squished into a point at the end. And if you give enough space for those events, you’ll never make it back to the Big Bang.

In truth, there are at least four different stories we want kids to learn: modern life, civilization, animals & plants, and the whole Universe. They operate on quite different scales. We need nested timelines to tell different stories.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Timelines externalize history. That is, they make it possible to hold all the things you’re learning about the world outside your head, so you can stand back and think about it. And they’re not alone.

Because “Life, the Universe, and Everything” is too big to fit easily in our heads, the most transformational tools that humans have ever invented have been the ones that externalize our thinking. So far, writing has been the most important one — it’s what’s moved us beyond MYTHIC (🧙♂️) understanding into ROMANTIC (🦹♂️) and PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬).

But there are other tools that externalize knowledge: calendars, infographics, maps, abacuses... Among those, timelines are pretty recent. Their precursor was “the annal” — a list of kings. Only in the mid-1700s did the graphical timeline appear.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

A timeline leverages a particular 🧙♂️METAPHOR (“time = distance”) to combine a bunch of events in a 🦹♂️LIST onto a 🦹♂️DIAGRAM to help us think about 👩🔬LIFE, THE UNIVERSE, AND EVERYTHING. Which is to say, timelines use the earlier kinds of understanding to make possible the later kinds. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

6. This might be especially useful for…

People who struggle to see how (in the immortal words of Susan Wise Bauer) “history is not a subject — it’s the subject”.

7. Critical questions

Q: Making our own sounds MESSY. Won’t this overwhelm students?

Yes, so start simple — with any group of kids, begin with just one empty timeline. Put it up, and then ask them where they’d guess certain events would go on it — where should we put the dinosaurs? where are cavemen? where should we put your birth?

Q: Which one would you recommend we start with?

Either the most recent stuff (the last few hundred years) or the 13.7 billion years since the Big Bang.

Q: Why poke into the future?

It’s the part of history kids will spend their lives in; putting it onto a timeline makes it seem more real.

Q: These sound hard to make. Can I just buy a premade one?

There are quite a few professionally-made timelines that are positively wonderful, and would make great additions to a classroom or living room. (In high school, I had the geek-famous Histomap of World History hanging on my wall; after college, I added the Schofield and Sims world history timeline (see this blog for better photos).

But you’ll get a lot more from making your own, warts and all:

for some kids, a pre-made timeline can be so full of information that it’s off-putting

getting to color and/or draw the images symbolizing each event helps kids feel that the timeline is theirs

choosing events that relate to what they’re learning in every class knits together what they learn

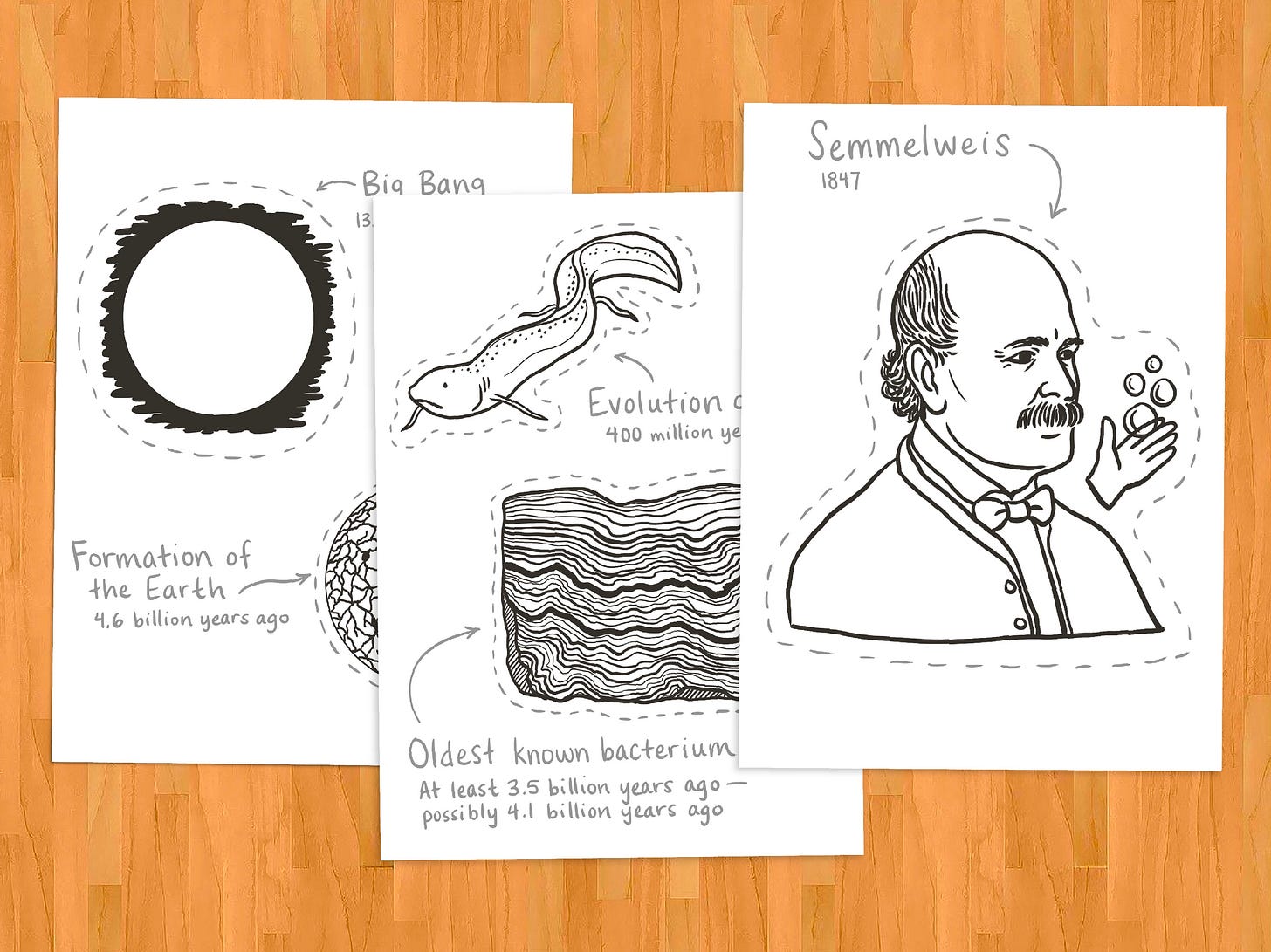

Q: Why should each event be an image?

The purpose of a timeline is to help us link events into bigger stories, so we want to keep the “cognitive load” of each event as small as possible. For this, 🤸♀️IMAGES are perfect — they fit in your mind (and burn themselves in memory) more easily than words.

Q: Couldn’t there be some happy medium between “pre-made” and “DIY”? Say, a kit to assemble?

Probably — and if anyone reading this would like to develop a kit to sell to others in the community, tell us in the comments below. We’d love to help you test it out! You might also check out the illustrations that Skylar is making for our timelines in Science is WEIRD:

The devil’s in the details. Become a paid subscriber to ask persnickety questions, and show off pictures of the timelines you’ve made!

8. Physical space

Timelines take a lot of space — probably more than any of the other one-or-two-hundred other patterns we’re working on!

Ideally, devote an entire wall to them. But if not, you can put one on the top of different walls (still hopefully in the same room).

9. Who else is doing this?

I remember walking into someone’s dining room for the first time, seeing a DIY timeline on their wall, and saying, “oh, I didn’t realize you homeschooled!” Which is to say that homeschoolers (and especially the classical variety) use timelines a lot:

There’s a little inspiration here from Montessori teachers, who talk about “Cosmic Education” and teach even very young kids about the chronology from the Big Bang on up:

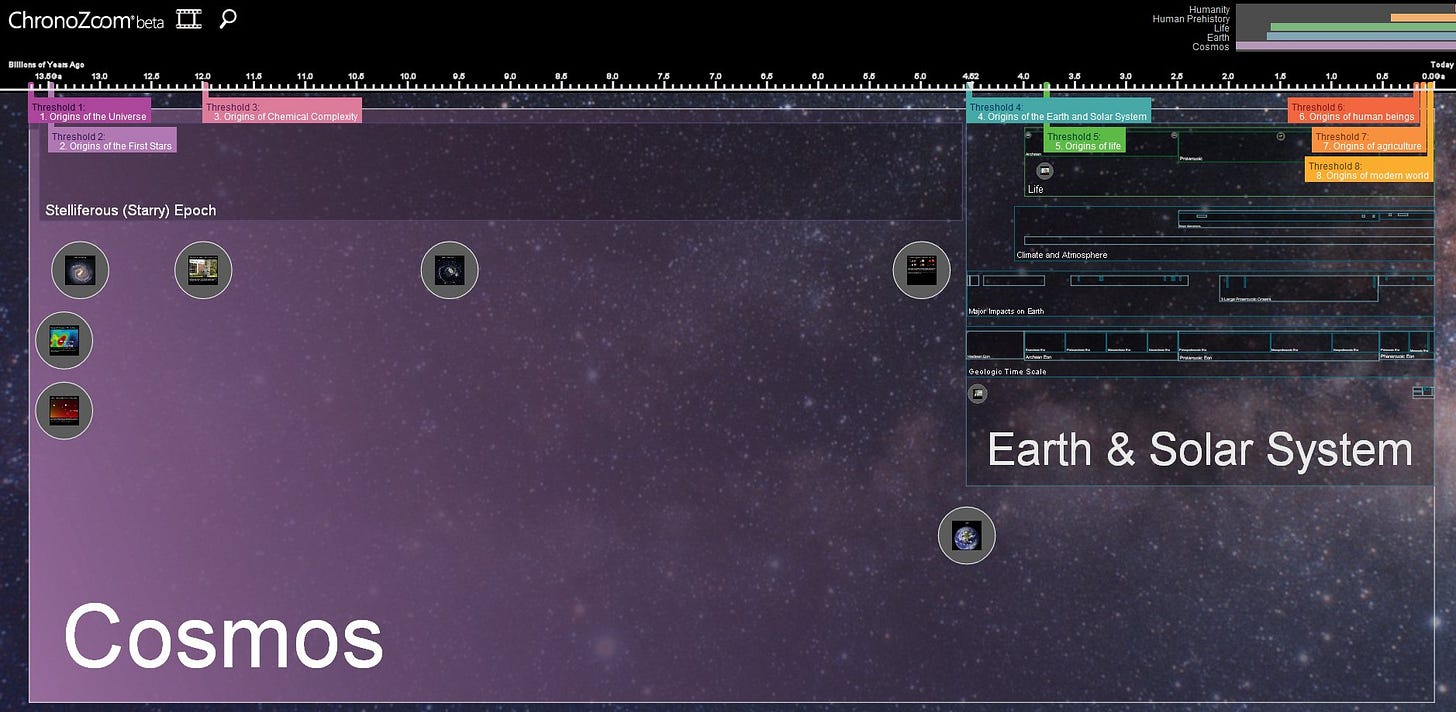

But perhaps the most direct inspiration comes from “ChronoZoom 2.0” — a project spearheaded by Walter “I Killed the Dinosaurs” Alvarez, part of the push in the early 2010s to get Big History into schools:

How might we start small, now?

Figure out how much of the world’s history you actually know. Stretch out your arm. Call the top of your shoulder “the cooling of the Earth”, and the tip of your index finger “this morning”. Now point to where, on your arm, you’d guess the following events happened:

when were there Stegosaurs?

where were the cavemen?

when do we find signs of the very first life?

Then poke around on ChronoZoom to see how well you did. Tell us how horribly you did in the comments!

10. Related patterns

In Egan elementary and middle school education, the role of history is to knit everything together into one giant narrative so kids can see how everything they’re studying has mattered.

Which is to say, we take history seriously! We stretch the scope to encompass the 13.7 billion year story of Big History°, so that history can include the facts of science. We spend the first four years moving through different periods of history, and once we’re finished, begin to repeat it — we call this Spiral History°. Throughout the first four years especially, we tell the Epic Stories° that birthed the world and the Origin Stories° of how we came to know stuff.

Afterword:

I mentioned a bit of Science is WEIRD’s “orientation” curriculum in this post; coincidentally, I just held our annual free open house to talk about our science classes — you can watch it right here. (This post actually gets a bit of a shout-out.)

Though he did think a lot about giants.

I have much love for the timelines. They're concrete, something which can be implemented _right now_, and I'm 100% convinced that they effectively convey valuable information to the audience.

Which got me asking myself "Why do I like the timelines so much? What is it about them that hits the sweet spot?". "Context at a glance" says me in response.

I'll assert that

1) Part of the problem with the "firehose of facts" approach to education is that it's hard to retain information absent some kind of a mental framework into which it can be slotted.

2) Understanding "the big picture" is an essential element in building the necessary context/framework.

Which leads me to the further question: Is there a context-at-a-glance equivalent of timelines for other subjects? A visual diagram of "this is how all this hangs together" for any particular subject could help immensely in making that subject digestible. Especially if you hang it in the classroom where people can see it every day?

History has the advantage of being linear; it's just one damn thing after another. (it's actually a cube, because it happens in place and time, but let's skip that for now). It's harder seeing how you can get the big picture for something like math, but maybe that's just my lack of familiarity with the subject. Something to ponder.

I recommend these two exercises:

1. Imagine compressing Sun's lifetime to a human scale. Let's say, 4.5 billion years is turned into 45 years, or 100 million years of real time converted to 1 "comressed" year. To what time the real human life will be compressed? Approximately to the time you'll need to read this statement.

2. Relabeling years works really well, especially around 0th AD. Say, it's year 2024; Jesus was born in 1995 and is now 29 years old. Rome is now ruled by Tiberius after Augustus' death in 2014. Augustus became a ruler in 1973, and Julius Caesar was assassinated in 1956. In 1920 Sulla was a dictator; in 1782-96 the second Punic War was fought; in 1643 Aristotle tutored Alexander the Great; Rome was founded in 1247; and Nefertiti was queen of Egypt at year 670.