“What do you think about classical education?”

Since starting this blog, I’ve been asked this question more than almost any other. I’ve held back on a full answer, because I knew it would be… complicated.

But today’s the one-year birthday of the blog, so I thought I’d dive in!

Once upon a time, I was in love with classical education: Susan Wise Bauer’s The Well-Trained Mind had a huge influence on me and my wife,1 and I’ve integrated some of classical ed’s practices of classical ed into my teaching.2

Beyond that, I love the lofty ideals of classical ed, its optimistic take on human potential, and even its fancy, flourish-y aesthetics. Reading about classical education rubs my belly in just the way it wants to be rubbed — heck, this substack is named after it! (The original “The Lost Tools of Learning” was an 1947 essay that helped launch the modern classical ed movement. We’ll be doing our next bookclub on it — keep reading for details.)

Once upon a time, I was in love with classical ed… and I sort of still am! But I’m not a partisan of it anymore. I stopped being one when I started tutoring high schoolers who had attended classical schools for many years. Some were just as brilliant as the brochures would have you believe, but many were just as illogical and confused about the world as their peers in public schools.

It took me a long time to understand why it didn’t work the way its backers promised it would — I only really understood why when I began to really understand Kieran Egan’s paradigm of education. And here it’s useful to note that Egan was, in his heart, something close to a classical educator. His own education (in Ireland, in the 1940s and ’50s) seems to still have been very academics heavy; he thought that every kid should learn about ancient Greece and Rome, and learn Greek and Latin roots. Heck, he even defends the use of repetition, writing puckishly of “the joy of rote learning”.

But, crucially, it didn’t work for him:

…I was never sure what sense it all made. Why did I have to learn to decline those Latin irregular nouns, or be able to prove that opposite interior angles of a parallelogram are congruent, or recall the provisions of the treaty of Ghent?

Much of the time I and everyone I knew was bored with schooling, and had difficulty relating what was happening in class with human life and its enhancement. My book is an attempt to show that, indeed, everything in the world is wonderful, but that schools are designed almost to disguise this slightly shameful fact.

And I found in his paradigm the stuff I most loved in classical education, infused — wonder of wonders! — with what I found best in a progressivist education.

Now that classical education’s becoming an actual force in educational reform, I think it might be helpful to everyone to point out what I see as the crack in its foundation — and to call attention to what I think its real genius is.

0. Leigh Bortins & science

The responsible thing to do, before writing an essay like this, would be to re-read my favorite books on classical ed. Alas, I’ve been super-busy with a secret project, and it was actually while working on said secret project3 that I happened to re-read a single chapter of a single book on classical homeschooling — the one on science in Leigh Bortin’s The Core: Teaching Your Child the Foundations of Classical Education — and I couldn’t stop thinking about it. So in the interests of keeping this to a manageable length (too late!), I’ll be focusing on that chapter, here.

To be clear, this isn’t just some random book on classical education. Bortins is a major voice in the homeschooling community, and as the founder of Classical Conversations, she’s been more important than maybe even Susan Wise Bauer for making classical ed a realistic option for normal people: there are people using CC in probably every medium-sized city across America, and beyond.

In my heart, I yearn to have a nemesis, and I think that there are quite a few branches of the multiverse where Bortins and I are truly excellent nemeses. (We definitely belong to different tribes — she minimizes evolution, for example, while I put it near the core of the science curriculum.) But I suspect that there are other universes where we’re great friends. There are definitely aspects of her curriculum that I’ve borrowed, and will be writing about on this blog. (Her insistence that kids don’t just need to label maps, but actually draw them is brilliant, and will show up, with some twists, in our pattern DRAWING MAPS°.) And, look, the sort of tribalism our society is trapped in is making us all stupider.

So while I won’t try to soften my criticism of parts of her chapter that I find, well, bad, I’ll steer clear of any tribal rumblings — and I’ll also not hold back my praise for the parts I see as insightful and essential.

(The danger of focusing on this, of course, is that any chapter can’t actually be a great stand-in for all of classical education, or even for Classical Conversations science program. So I’ll invite you to draw a fuller picture in the comments. Oh, and I welcome your critiques of my stuff there, but I’ll be deleting anything that could be interpreted as a tribal critique of Bortins.)

I’ll give my thoughts roughly in the order she lays out her sections: she tells parents to (1) begin with names, (2) add in facts, (3) not sweat the experiments, (4) help kids go deep in research, and (5) orient themselves to the true goals of science education. Then I’ll touch on one final thing she says, and give an overall explanation on what I find wonderful and wanting about classical education.

1. Begin with names

Bortins writes:

Classical educators begin by teaching children to define terms. You may be getting the impression that the best thing parents can do to educate their young children is to spend time with them naming things. That’s right! I told you the model was simple. (p. 184)

I love this fiercely.

She goes on to say that classical ed parents should teach kids (for example) the names of birds, the names of trees, and the names of constellations and planets they can see.

I think that Egan’s paradigm can actually explain why this is so wonderful. 🧙♂️NAMES are a humble tool in Egan’s Mythic toolbox, but they pack power all the same. We intuitively understand names: they’re perhaps the first piece of spoken language that children learn, and they allow us to talk about the world with others: knowing “maple”, “oak”, “cedar”, “fir”, and “linden” allows you to think about trees much better, and knowing “Balsam fir” vs. “Fraser fir” vs. “White fir” vs. “Noble fir” allows you to think much better still.4

🧙♂️NAMES are something we give to other people, of course, and that flavor carries over to everything else that we name: as Bortins writes,

We feel more intimate with the creation that we can name. (p. 184)

Yes, yes, yes! And it shows how powerful classical ed can be by borrowing even a few of Egan’s tools. (If you’re new to this substack, and don’t know what we’re talking about with “Egan’s tools”, you’ll want to take a look here, and then maybe poke around my review of his book, The Educated Mind: How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding.)

To see the power here, compare this to the milquetoast blend of progressivism and traditionalism that you’re likely to see at your local public elementary school — or at least the one that I went to. There, we were focused on 👩🔬CONCEPTS. But, as Bortins is fond of pointing out, a conceptual understanding can only be knit out of knowledge, and the well-known problem with progressivist education is that it tends to shirk from feeding students a lot of knowledge.5 🧙♂️NAMES allows classical science education to begin by connecting kids to the real world.

So far, so wonderful. This is something that Egan educators should emulate.

2. Add in facts

Of course, names aren’t enough — we need facts:

Obviously it is impossible to memorize every fact of science, so it is important to choose foundational facts that frame the major discussions within broad scientific categories and memorize these facts over a long period of time. (p. 181)

She recommends working on one fact per week: say, the types of stars, Newton’s laws of motion, or the periodic table of elements. Commit it to memory. Unpack it a little.

I think this could be done well, but her examples worry me; they feel quite inert. And, once again, I think Egan’s perspective can help us see why.

Fun fact: FACTS are nowhere to be found in Egan’s list of cognitive tools. Why not? Because while knowledge is key to an Egan education, the format of facts is not. By themselves, facts are dry, as dead as a shriveled-up apple — and the very goal of an Egan education is to bring them back to life. Egan writes:

The point is not to get the symbolic codes as they exist in books into the students' minds. We can of course do that — training students to be rather ineffective “copies” of books.

Rather, the teaching task is to reconstitute the inert symbolic code into living human knowledge.

(Children’s Minds, Talking Rabbits, and Clockwork Oranges, p. 51)

I was once charmed to discover that Egan habitually uses four different re- words to describe what we need to do with facts:

re-embed them (bring back their human context)

re-constitute them (bring back their water, as if facts were freeze-dried fruit)

resuscitate them (bring back their air, as if they had drowned)

re-animate them (bring them back to life, as if they had died while being stored in a textbook)

Imaginary Interlocutor: But don’t great classical educators do this?

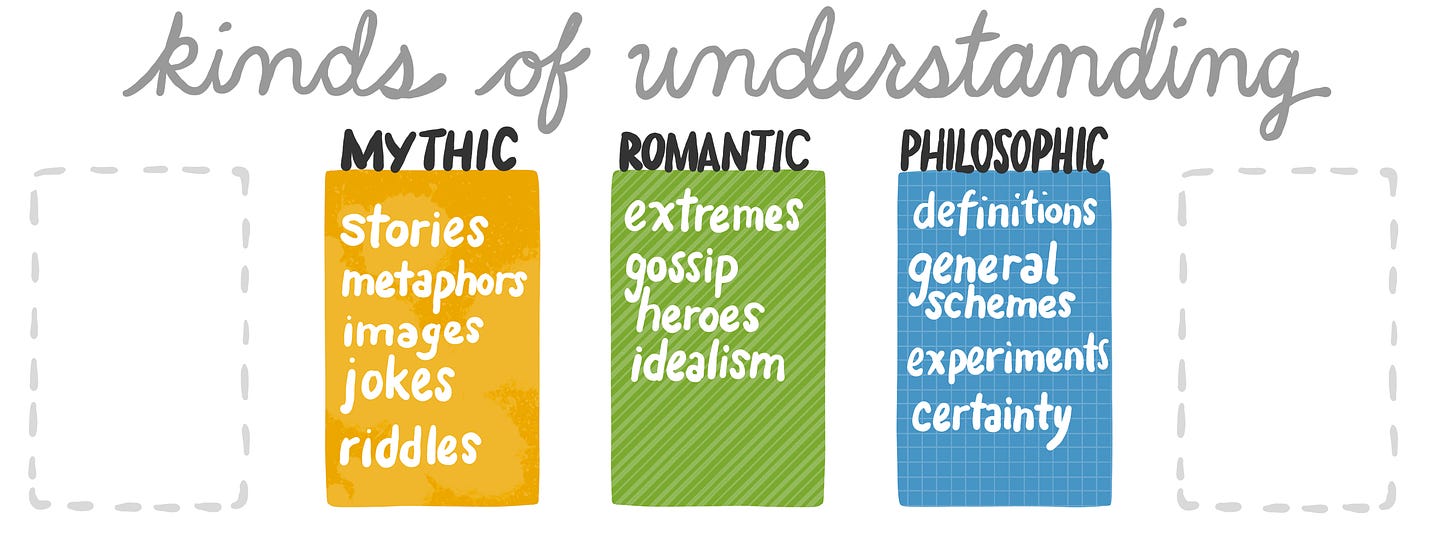

They absolutely do — in fact, that’s a lot of what we mean by the phrase “great educators”. However, we need to acknowledge that this is a hard job. Egan tries to solve this not by assuming we have an infinite supply of great educators, but by building a solution into the curriculum itself: use the tools. Especially, use MYTHIC tools (like 🧙♂️STORIES, 🧙♂️METAPHORS, 🧙♂️RIDDLES, 🧙♂️MENTAL IMAGES, 🧙♂️JOKES, and 🧙♂️GOSSIP) and ROMANTIC tools (like 🦹♂️THE STRANGE and 🦹♂️THE HEROIC) to infuse knowledge with emotion and meaning.

To be fair, in another section Bortins does praise using 🧙♂️STORIES — but mostly as an add-on. Her advice here, though, is so practical that it’d be a crime not to share it: put a lot of science books in your home!

Be sure to ask friends and librarians about good science books and stories. The Internet has dozens of lists of books about scientists, the history of science, and science facts by topic and reading level. If you start a book and don’t like it, put it down and choose another. Science magazines are usually the best source for current information and can be of interest to all ages. (p. 191)

In any case, what’s essential is to memorize these facts. But this must even seem odd to Bortins, because she continues:

Rather than memorizing a list of facts as we do in history, I changed the format a little by changing each science fact into a question and answer to memorize. Scientists should learn to ask questions, so this seems like an appropriate way to both memorize data and model inquisitiveness. For example, my students memorize: “What are the types of volcanoes?” active, intermittent, dormant, extinct. (p. 181)

Be honest: does it seem odd to you that she moves from “[s]cientists should learn to ask questions” to a list of types of volcanos to memorize?

Like FACTS, QUESTIONS are nowhere to be found in Egan’s list of cognitive tools. When I first realized this, I thought it was stupid. I pressed Alessandro: surely, I said, questions need to be included; our ability to ask questions rivals even 🧙♂️STORIES as one of the most powerful ways we have to understand the world. Initially, he pushed back. QUESTIONS, he told me, aren’t on the list because if they were, people would just use them badly. QUESTIONS are already part of schooling, but they’re typically used to spark excitement or open up wonder but just to elicit a correct factual response.6 (For what it’s worth, Alessandro — hi, Alessandro! — totally caved. We’re still searching, though, for a name that carves off the good use of questions from bad ones. 🧙♂️GOOD QUESTIONS is as far as we’ve got at present; obviously, we should improve this.)

And indeed Bortins seems to realize that these questions, too, are rather bland, because she suggests using another of Egan’s cognitive tool, 🧙♂️GAMES, to spice them up:

A fun way to drill the questions and answers is through a game like Jeopardy! (p. 182)

What would you guess I’m going to say about this, from an Egan perspective?

Look: everyone loves Jeopardy! And a year ago, I would have thought this was a good use of the tool. But then Alessandro pointed out that Egan seemed reluctant to include 🧙♂️GAMES in his list, and for the same reason that he was loath to include QUESTIONS: trivia games are what teachers resort to when they haven’t yet re-animated the information they want kids to learn. And while playing a trivia game might make a lesson more fun, it’s not likely to kindle an actual love of the knowledge in children. If memorizing disconnected questions-and-answers isn’t working for your kid, then throwing in a few Jeopardy!-style games isn’t likely to fix the problem.

This brings us to what I think is the first challenge of classical education: because it doesn’t bring in many of the tools, classical education mostly works for Ravenclaws. But we need schools and homeschooling options for Hufflepuffs, too. (And Gryffindors. And, God help us, Slytherins.)

Egan education can improve on this precisely because it puts tools like 🧙♂️STORY and 🧙♂️JOKES and 🦹♂️THE STRANGE and 🦹♂️THE HEROIC at the center of learning.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Which of those is a good replacement for “questions”?

One that Egan didn’t make as big a deal of as he ought: 🧙♂️RIDDLES. A riddle is a question with an answer you already know, but don’t know that you know. To figure it out, you have to puzzle out what’s going on, and learn to see the world in a new way. And the answer to a 🧙♂️RIDDLE can stick in memory much better, because it opens up curiosity.

Imaginary Interlocutor: I’m not sure I’m seeing the difference. Examples?

When I taught the Science is WEIRD course in volcanoes a few years ago, I made our first weekly riddle, “What’s a volcano?” and designed the answer to be surprising: “A pile of frozen lava”. Another was “Why is the Earth so hot?” and the answer was “It’s a nuclear power plant.” Another was “Why do volcanos surround the Pacific Ocean?” and the answer was… well, the answer was so cool that it constitutes a spoiler, and I’m not going to say it here! (I’m remaking the course for later this year, and I know some students read this blog.)

But this seems important: a good science course should have spoiler warnings, because real science flips our assumptions upside down. Learning that the four types of volcanoes are “active, intermittent, dormant, and extinct” just adds facts.

So if I think that Egan educators can benefit from leaning more heavily on 🧙♂️NAMES, I think that classical educators can benefit from leaning more on all the lost tools of learning… especially 🧙♂️RIDDLES.7

3. Just chill out about the science experiments

In this section, I went back to loving Bortins. She knows that parents of young kids feel obliged to conduct “science experiments”, but she assures them that they needn’t fret:

don’t worry about elementary science experiments lining up with the students’ science memory work or the literature they read…. Most memorable science investigations with children are going to occur serendipitously and may seem unrelated to their formal studies. (p. 188)

YES, THANK YOU, LEIGH. I freaking hate kids science experiments: educationally, they’re a near-perfect vacuum. So much time and effort is spent on them, and what we get is a simulation of knowledge: What did any of us learn from doing “egg drops” beyond “it’s fun to smash things”?

4. Do some research and make presentations

This part… sigh. It’s where we can begin to see the crack in the foundation of classical schooling.

Kids should create their own textbooks, Bortins writes,

to really study material and not just answer the questions at the end of a chapter or on a worksheet (p. 190)

Yes! Cool! Great! (In Science is WEIRD, I also have kids make notebooks, though I think I first got this idea from the Waldorf people.) But what does it look like to “really study”, in classical ed?

They should appreciate glossaries, thesauri, indexes, and dictionaries as tools that help them learn many new things. It is slow for children to look up the information rather than just telling them the answer, but saying “Look it up...” will make them pay attention so they don’t have to look it up again. (p. 190)

A thesaurus, as a tool for learning science? As a science teacher, I find that… strange! It gets stranger:

Students need to know how to make their own vocabulary lists in any subject or language they study and arrange them alphabetically in the notebook they use to record information on that subject. (p. 190)

As we’ve been talking about in the Learning in Depth cohort, 🦹♂️LISTS can be an oddly powerful tool to explore new information. But passively writing down a list of vocab words, and listing them alphabetically... well, this isn’t the literal worst way to spend your time, but this is assuredly not a recipe for deep scientific understanding.

Why is she advocating this? I was confused, until I read:

The most important aspect of the research is that they get to practice their rhetorical skills and share what they’ve learned. (p. 192)

Q: Wait, why would rhetorical skills be the “most important aspect of the research”?

An excellent question — and one that points us back to the foundation of classical education, in that essay by Dorothy Sayers (friend of C.S. Lewis! writer of detective novels!) which we keep dancing around: “The Lost Tools of Learning”. That essay is so important (and fun to read) that we’ll do it as our next book club:

3pm Eastern / 12pm Pacific

Saturday, October 5

For paid subscribers only; you can register here

But the tl;dr for right now is: the foundation of modern classical education is the Trivium.

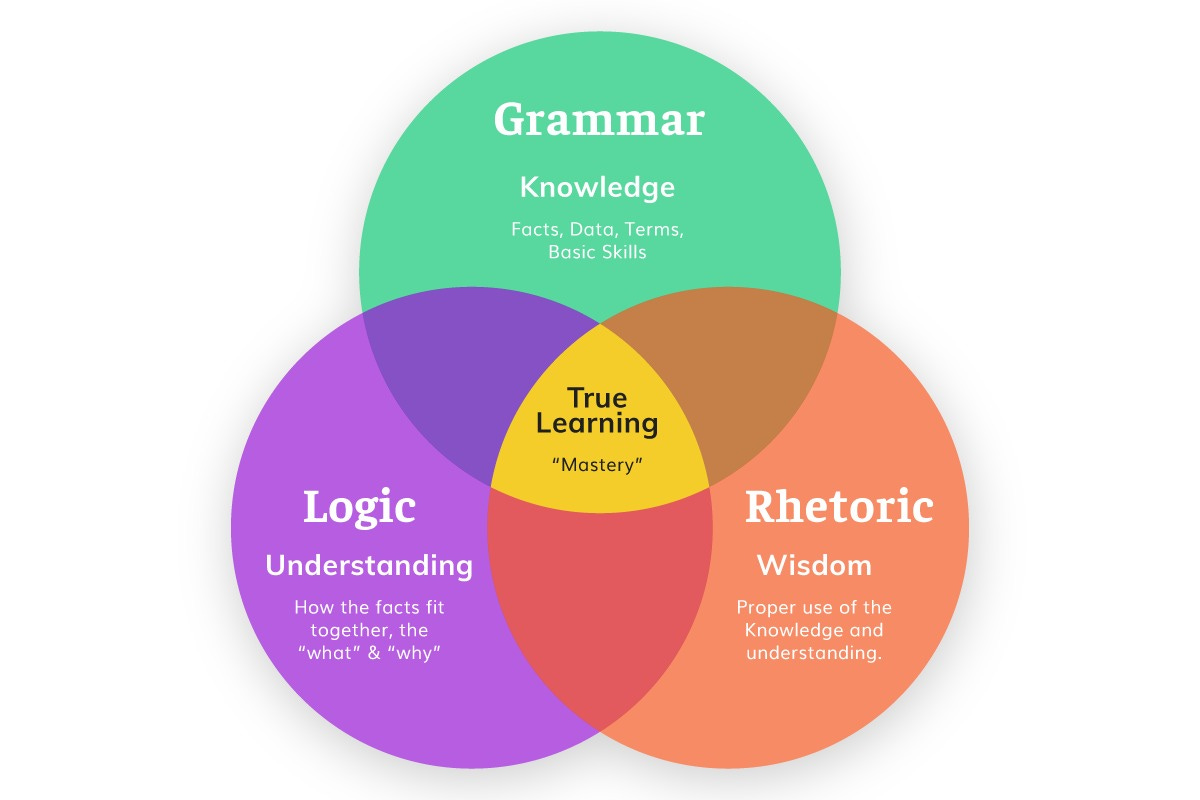

“Trivium” is Latin for “three ways” (“tri-via”), and, well, it does what it says on the tin: classical education borrows from the Greek and Roman worlds the notion that there are three important ways to know something:

Now, that image (and all of the other ones I could find) includes some hifalutin spin-doctoring: so far as I’ve been able to find, the original use of the Trivium had much more literal definitions of these: grammar meant “learn the grammar of Latin”, logic meant “no seriously just learn Aristotle’s logic”, and rhetoric meant “learn how to convince others you’re right”.8

So why is Bortins talking about practicing rhetorical skills during science? “Rhetoric” is a big deal in classical schooling. Which brings us to her next section,

5. Orient around the goals for science

Classical ed has many strengths, but one of the the biggest is that it already exists. You can buy specific curriculums, find online communities, that sort of thing. It’s already been fleshed out, from kindergarten to college, by hundreds of schools. (Egan education, in this regard, is still lacking. Though, keep reading!)

The helpful thing here is that we can ask “where is my kids’ science education headed?” and get a clear answer. What will classical kids be doing with science in high school?

I want my children to practice the dialectic and rhetorical skills while studying high school science so that they are not too intimidated to read great scientific documents [she later cites Aristotle, Galileo, Newton, Darwin, and Einstein], or to logically argue with scientific fads such as weight loss schemes or medication scares drummed up for publicity. (p. 192)

Wait, I wanted to scream when I read this, the climax of twelve years of science is to not get fooled by “eggs are bad for you again” articles and read dead scientists?!

Imaginary Interlocutor: But surely those are good things?

Agreed! In fact, I think that the history of science is even more important than Bortins treats it as — we should fold it into every part of the science curriculum. And as someone who wants students to think about worldviews, I think that reading the seminal works of science has a place in the curriculum.9

But as an ultimate goal for science, this is insufficient.

By the end of an Egan education, we want kids to actually understand the Universe, not just in its shiny scatteredness but in its utter simplicity. Over billions of years, a singularity has spun itself out into a wild diversity; dinosaurs are made of cells that are made of molecules that are made of atoms, and the processes that whirled those into being are themselves simple and mostly comprehendible — you can describe a shocking amount of it with a few simple mathematical formulas.

Understanding the Universe is, for lack of a better word, spiritual work.10

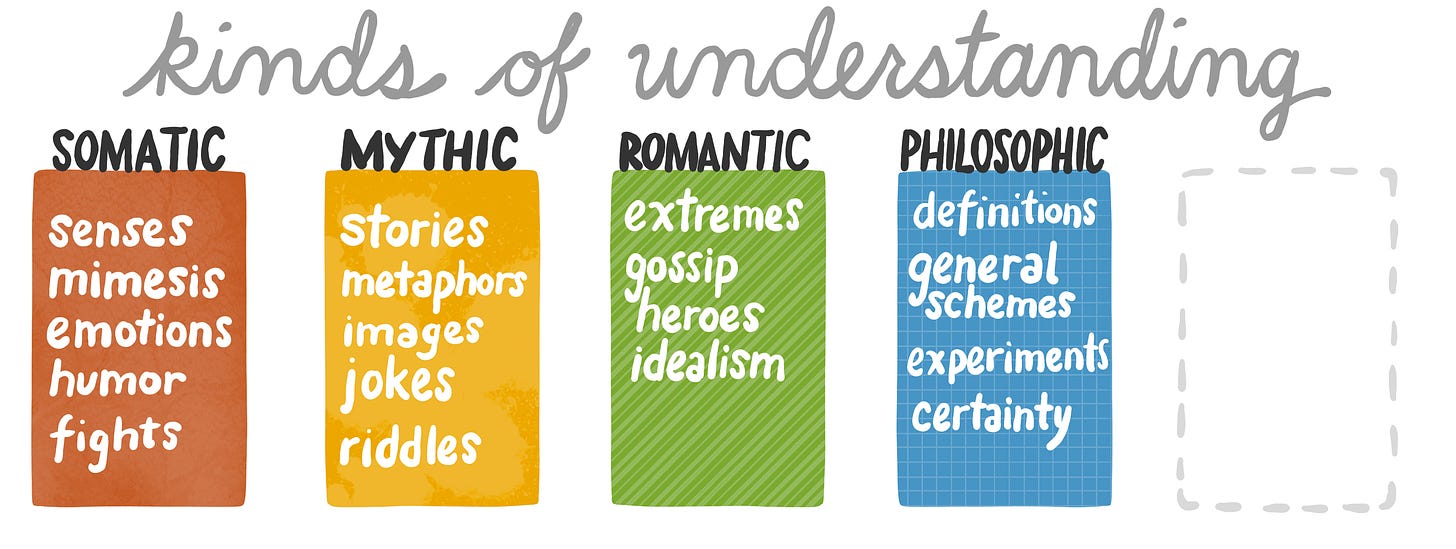

Egan education gives us a road map for getting there. We should invest time delighting in 🦹♂️THE STRANGE and move into 👩🔬THE QUEST FOR TRUTH. We should, that is, progress from ROMANTIC (🦹♂️) understanding to PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) understanding. And that should provoke feelings in us: flashes of awe and transcendence.

And in Egan education, we want even more than that. We want to root our kids in the MYTHIC 🧙♂️LORE of the bold explorers who’ve come before us, and realize that we can stand on their shoulders and see even farther. We want them, finally, to realize that everything that we understand is but a tiny shard of the Universe, and apprehend 😏THE GREAT MYSTERY. As Newton told his nephew:

to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and… now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

Or, as Kieran Egan said:

We represent the world to children as mostly known and rather dull. The opposite is the case: we are surrounded by mystery, and what we know is fascinating. My book is an attempt to show how we can reconceive the school and the process of education to engage students’ emotions and imaginations with knowledge.

–Kieran Egan, actually the very next lines of that same interview

Imaginary Interlocutor: What are these WEIRD WORDS YOU KEEP EMPHSAZING?

They’re Egan’s kinds of understanding, more fundamental to his thinking than even the tools. (Arguably, they power the tools.) They’re some of humanity’s greatest creations, spanning the pre-modern to the modern to the postmodern.

Probably we can see their power best through an example — let’s take ecology.

First, imagine being a hunter-gatherer living 10,000 years ago, moving down the Eurasian steppes. In the sky you see the silhouette of a crane, and know that means there are rivers ahead, which means frogs and rushes and fish; you could build a home here.

Now, imagine being the bold explorer Alexander von Humboldt, climbing Ecuador’s Mt. Chimborazo and realizing that though all the species were different, the types of plants you’re seeing precisely mirror those that grew at the same elevations in the Swiss Alps:

Finally, imagine being a post-doc ecologist living in Cincinnati, making quantitative models on a computer comparing a marsh with a hypothetical ecosystem found on a methane-cloud planet.

Which of those ways of understanding ecology is the most profound?

The answer, Egan suggests, is that they’re each profound, each deeply human, in different ways. The first he calls MYTHIC understanding, the second he calls ROMANTIC, and the third PHILOSOPHIC. These have been unlocked by societies over hundreds and thousands of years. And over the curriculum, we can help kids experience all of them.

In place of this, classical ed just has the Trivium.

What we’re seeing here is that classical education probably doesn’t provide the best foundation to regularly help kids make emotional sense of the Universe. And, I submit there’s something very odd about this. If you read lots of books on education, you know that classical ed books are way more interested in emotions. (The prize for “most moving” has got to go to the super-Catholic Beauty in the Word: Rethinking the Foundations of Education, by Stratford Caldecott). But when I read them, I don’t see them actually providing the means to help students experience those emotions.

I’m not alone — historically, classical schools are famous for graduating people who say they found schooling horribly dull. (This was the grounds for Progressive reformers to create the “practical” curriculum that de-emphasized academic content.)

Look: I’m no longer a champion of classical schooling. But I desperately want it to succeed — and I think integrating MYTHIC, ROMANTIC, and PHILOSOPHIC understanding, and the tools they power, is the way to do it.

A few months ago I got three minutes to pitch a famous Catholic theologian (and booster of classical education) on Egan. I prepped for it for a month… and then only a few minutes after I was done realized I should have just said one sentence: I think this approach is the secret to revitalizing Catholic schooling.

He who has ears to hear, let him hear.

6. Embrace science in real life

There’s still one more section in the chapter, and it’s truly her best:

Our lives today are removed from basic science…. Today’s children don’t receive as thorough an understanding of science compared to the child who rose at 4:00 a.m. and helped his mother milk the cows and his father plow the fields…. [S]cience has become a sort of artificial curriculum. (p. 194–195)

Bortins is emphatic: help your kid experience nature. She writes gorgeously about her kids planting, weeding, building a deck, hunting, fishing, and naming stars by firelight. She knows that for some families, this will be too “outdoorsy” — but (wisely) emphasizes that you can get a lot of nature connection from just a little effort:

if you dig a hole under a brick or log, you can experience real science (p. 197)

And if even that’s too much for you, she adds you can always invest more time into indoor cooking, sewing, dissection, and building electronics. Beyond all that, there’s just listening —

Learning to listen will allow them to ask one day about the Doppler effect… or why dogs and young children can hear a broader range of sounds than adults. Listening inspires curiosity. It pleases parents when children observe something special among the mundane. We want our children to have curious, observant senses. So, find opportunities to be quiet as a family. You may be surprised at the roar of heartbeats, distant trucks, fans cooling, and airplanes jetting by. (p. 181)

This is, literally, wonderful. (And I’ll be testing out “be silent” as a pattern.) But there’s something interesting going on here: where is she getting this from? Not, certainly, from the Trivium. This is more deeply human than classical education, something charged with emotion and meaning that would lose its soul if it were squeezed into “grammar” or “logic” or “rhetoric”. But what is it?

Again, Egan helps us understand what’s going on: all those other kinds of understanding are anchored in a truly fundamental kind of understanding, one that comes before MYTHIC and ROMANTIC and the rest, one that speaks to our animalness: SOMATIC (🤸♀️).

Before we know anything through our stories or logic, we know it through out bodies. And when we realize this, we can create a truly profound science education for people of all ages and all ability levels.11

7. The crack in classical education… and what makes it great

The trouble is, FACTS are dead, and classical education doesn’t come pre-packaged with the tools or structure to bring them back to life. Why?

We’ve already talked about two reasons. First, it tries to do too much with weak tools — FACTS and QUESTIONS. Second, rather than using the kinds of understanding that humans have used for hundreds, thousands, and hundreds of thousands of years — SOMATIC, MYTHIC, ROMANTIC, and PHILOSOPHIC — it uses the Trivium.12

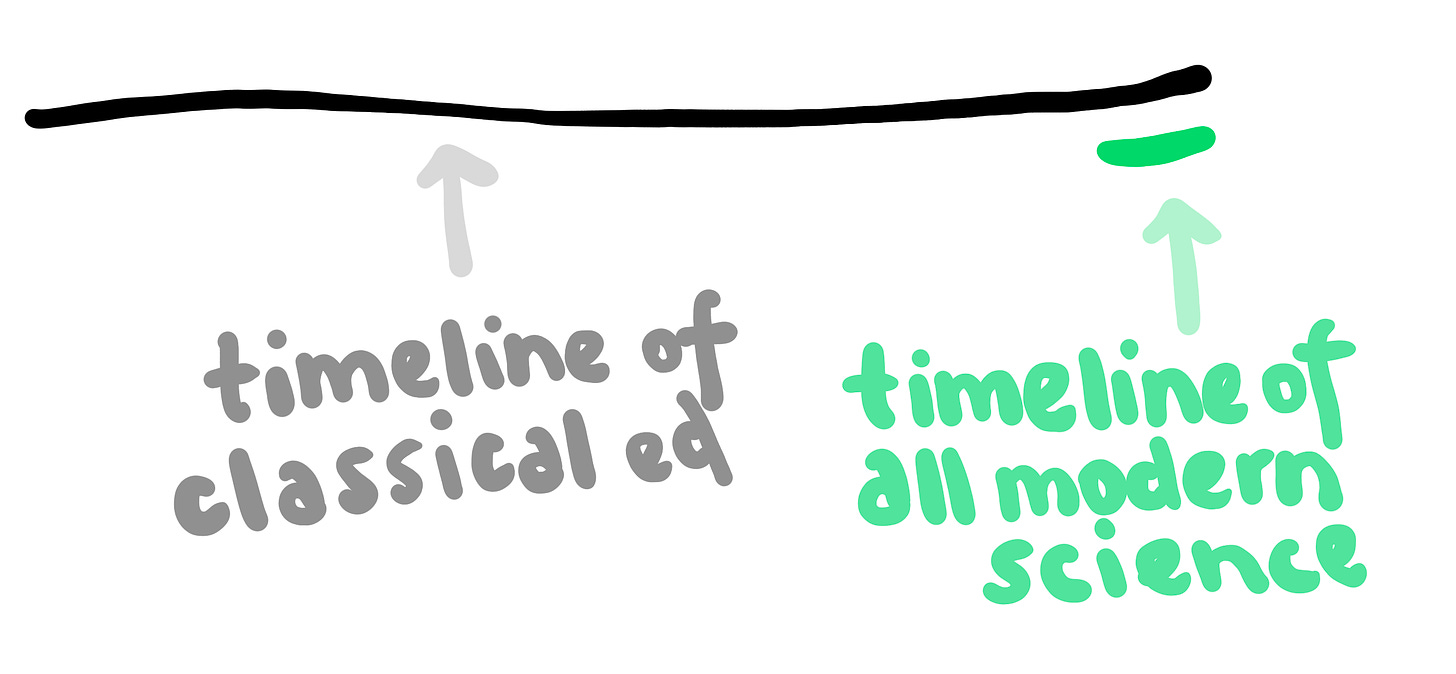

But there’s a third reason that’s particular to science: classical ed wasn’t made to deal with modern science, because it’s ten times older than modern science. Modern science is about two centuries old, but classical education got its start two millennia ago.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Are you saying that classical education is bad because it’s old?

Not at all — I like old things! (I’m a humanities person at heart, and was confused when I heard someone in my M. Ed. program say, “obviously, newer citations are better than older citations”.) But if classical educators are correct when they insist that history matters, it’s worthwhile to note that when classical education was fine-tuned in the Middle Ages, science really was just names and facts. (There had been important science done in the ancient world, but much of it was still lost.) This neatly explains, I think, something curious: in Bortins’s book, the best science ideas are precisely those which don’t come from the Trivium.

So, if the foundation of classical education is so weak, then why is classical education so wonderful? What’s classical ed’s secret sauce?

A lot of answers could be given. They take history seriously (remember that our SPIRAL HISTORY° is a modification of Susan Wise Bauer’s system). They take order seriously; this helps students and faculty feel safe and respected. I’ll invite more hypotheses in the comments below. But beyond all that, I think there’s something bigger: classical education has attracted some of the most imaginative minds in education. It’s pulled in many of the most thoughtful writers (the Catholics, in particular, punch above their weight), and many of the most dedicated and serious teachers.

The heart of classical education isn’t the theory, it’s the people. And this is why I’m especially eager to connect the classical education and Egan education communities — I hope that we can get some of their wisdom in getting this off the ground.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Pardon me, I’ve been distracted for the last twenty minutes. Could you just give us the tl;dr of what you’re saying, perhaps in a good news / bad news format?

The good news is that classical education is simple — there’s something wonderfully focusing about just asking “hey, what’s the most essential stuff for an educated person to know?” and then building the curriculum around that.

The better news is that when classical ed works, it often works gloriously, easily outshining mainstream education that keeps hoping to kindle the fire of learning in kids without feeding them knowledge.

The bad news is that it mostly only works for Ravenclaws — that is, people who have an innate love of academic information.

The worse news is that this slows the growth of classical education, and makes us under-appreciate just how amazing the educators who make classical ed work really are.

The best news of all is that the classical ed community has shown itself to be willing to assimilate good ideas that come from outside the Trivium — reading stories, touching grass… — and that there’s a whole ’nother approach to education that they might love.

Imaginary Interlocutor: I apologize that I’m so distractible — that’s STILL too complicated. Why aren’t you a classical educator, in three words or less?

I’m too lazy.

It’s devilishly hard to be a classical educator — it takes more energy to bring the excitement and emotion and mattering than I have. The reason I love Egan’s paradigm is that it puts mattering at the core, and builds everything around that. It makes it easier to re-humanize education.

9. Getting this off the ground

Oh yes, about that! I said that one of the many excellent qualities of classical education is that it’s fleshed out. Well: we’re about to take a step in that direction. In a few weeks, we’ll be launching our Kickstarter for the first-ever Egan-powered homeschooling guidebook.

It’ll be a here’s-what-you-do book (similar in scope to Bortins’s) for doing history and geography, life and physical science, arithmetic and problem-solving, reading and writing, art and practical life skills, philosophy and world religions and more with your kids.

It’ll include some of the patterns from this blog… but also quite a lot that hasn’t been on this blog. And it’ll make it practical — tell you precisely how to do it, so you can focus your own energy on your kids.

I plan to self-publish it next summer, in time for the 2025–26 school year. And I want it to be practical… which means I’ll need people to be trying parts of the system out ahead of time and giving feedback. My plan is to make an online community of people with advanced copies, and to invite in Kickstarter backers.

This, I think, is the second step in getting Egan education into existence. (The first step is the Egan Pattern Language on this substack. And the third probably has something to do with translating it to schools.)

Interested? Keep reading; I’ll be posting more about it soon.

And, if you’d like, keep commenting. Thanks especially to all the paid subscribers who’ve been making it possible for me to occasionally write longer essays like this. What can I say: you’re invited to the book club!

My hope for this particular essay is to open a dialogue with the classical education community. If you’re a part of any such groups, you might do the world some good by sharing this in them — especially as their critiques of what I’m saying can move this conversation forward.

Here’s to another great year.

At one point we, um, might have put up a framed photo of her in our living room. [Edit: hilariously, the first version of this said that Bauer had written The Educated Mind; nope, that’s Egan’s! The title of hers is The Well-Trained Mind. That I confused them, I think, is a sign that both systems are trying to achieve similar goals.]

From the humanities, especially: geography, the epic stories of the world, and timelines. (Look for a pattern soon about how to improve these with nested timelines.)

Irritated that I keep saying “secret”? I’ll actually announce it in this post — keep reading!

This sort of approach inspired me to write our patterns of STAR LORE° and LOCAL BIRDS°, with more to come. Each of those is classical at the core, and Eganized at the fringes.

Defending this statement is outside the scope of this post, but if you think this isn’t true, feel free to say so in the comments.

What’s the capital of Tanzania? If you said, “Dodoma”, congratulations, you get a star!

NOW DO YOU GET WHY I GAVE THIS NAME TO THE BLOG???

I find that a lot of classical ed folk don’t know the history of how their tradition changed; I’ve found the most helpful explanation in a great book advocating for the secular revival of classical schooling, Trivium 21c: Preparing Young People for the Future with Lessons From the Past, by Martin Robinson. This would make a great supplementary reading for our next book club.

If you’re into this sort of thing, I recommend The Book of the Cosmos: Imagining the Universe from Heraclitus to Hawking.

I find some of my fellow agnostics hate that word; all I have to say is, if Sam Harris can say “spiritual”, you can use it, too.

See, for example, our patterns KNOW A PLACE°, KNOW A TREE°, and STRANGE SENSATIONS°.

Just as an interesting sign of this, Bortins confuses “🧙♂️NAMES” with “👩🔬DEFINITIONS”. I know I’m risking coming across as pedantic here, but these are quite different tools! A 🧙♂️NAME allows you to refer to a thing; a 👩🔬DEFINITION is a fence to precisely divide one concept from others. It’s useful when we want, in PHILOSOPHIC understanding, want to get hyper-specific on how we’re using our words so that we can arrange our names into huge theories.

Love this post! My wife and I were actually just checking out Classical Conversations this week, and we had some similar reservations.

A note on games: I've used (for example) Kahoot! quizzes in a few different classes, both as a student and as a TA. They're actually pretty useful as a quick assessment tool. It can help you figure out if a class actually understands what's going on without needing to call on every person individually.

But as a study tool, I agree that gamification doesn't really work. To quote my favorite essay ever, _The Weight of Glory_ by C.S. Lewis:

"There are different kinds of rewards. There is the reward which has no natural connection with the things you do to earn it and is quite foreign to the desires that ought to accompany those things... The proper rewards are not simply tacked on to the activity for which they are given, but are the activity itself in consummation."

Lewis mostly was interested in how we think about heaven when he wrote this, but I think his insight applies equally to education. The proper reward for studying a subject well is that you eventually understand and enjoy it. Shifting the focus of a class to some unrelated game risks undermining that proper reward.

However, Lewis continues with an example that is directly related to classical education:

"An enjoyment of Greek poetry is certainly a proper, and not a mercenary, reward for learning Greek; but only those who have reached the stage of enjoying Greek poetry can tell from their own experience that this is so. The schoolboy beginning Greek grammar cannot look forward to his adult enjoyment of Sophocles... He has to begin by working for marks, or to escape punishment, or to please his parents, or, at best, in the hope of a future good which he cannot at present imagine or desire."

Lewis himself was, of course, classically educated. So I'm assuming this last sentence accurately depicts the way that most classical educators think about motivation (or at least did historically - it may have changed in the last hundred years). Namely, making education more interesting for students is nice sometimes, but it's more important for students to learn the discipline to study a subject for months or even years before they receive any real payoff. And in the long run, the effort they put in will be worth it.

I think you (and Egan) would disagree with this. I've never tried to learn Greek, but I can quickly think of some easy ways to incorporate Egan's tools - e.g., illustrating vocabulary words using stories from Greek mythology.

It sounds like the main difference between you and someone like Leigh Bortins is that you would rework the whole curriculum to center around the stories, where she would just toss them in occasionally for a bit of flavor. Does that sound right?

There's so much to like here!

1.

In a lot of myths and stories, knowing someone or something's real name gives you power over them. Naming things is a form of magic spell! The Bible is quite big on this too, from Genesis 2:20 "And Adam gave names to all cattle, and to the fowl of the air, and to every beast of the field" to Exodus 3:14 where Moses asks the Lord's name and gets the famous "I am that I am" back - one, admittedly unorthodox interpretation of this is that the Lord is not willing to share his true name with Moses, because magic. And in Jewish culture, the four-letter name is not spoken these days but paraphrased as HaShem (literally: The Name) out of respect. So yes, names matter.

(I think it was Scott Alexander who said when he was a child and learnt some Japanese words, he asked "Why don't the Japanese call things by their true names?")

2.

If I had to choose between a full-on classical educator and a full-on "progressivist" as State Director of Education, I'd probably vote for the former, in the hope that then at least some children would learn something in school.

But that's just projecting everything down to one dimension. Just like politics doesn't live on the single axis from liberal to conservative - some models measure economic and social liberalism/conservatism separately, for example (which at least gets you that libertarians are a separate cluster in 2D space).

Since this is a serious discussion on education, it's time to mention one of my favourite Harry Potter fan pages - which came up in the back of my mind even before you said "Classical education just works for Ravenclaws". It's the "sortinghatchats" model where you are sorted into two houses: your primary is why you do things (Ravenclaw: because systems, Hufflepuff: because people, Gryffindor: because honour, Slytherin: because loyalty) and your secondary is how (Gryffindors charge, Ravenclaws plan, Hufflepuffs toil, Slytherins scheme/improvise). The primary/secondary distinction doesn't mean one is more important than the other, just that we have a 2-dimensional model and we needed names for the axes.

In this model, Ravenclaw secondaries are the ones who like lists and facts and would get most ecstatic at the thought of Learning in Depth, whereas Ravenclaw primaries are the ones who get something out of science experiments, I think? The kind of person who asks why fluoride and chloride have properties in common, and ends up inventing the periodic table.

The point here, to me, is that if we want school to work for people who are not double Ravenclaws, then we have to address both the "how" and the "why". Classical education has some gaping holes here, which the progressivists can legitimately contribute to filling, and Egan's suggestions (in my reading) touch much more on reaching people across both primary and secondary houses. Maybe Gryffindor primaries (intuitive "felt" morality) will be inspired more by the mythic and especially romantic, and Ravenclaw primaries more by the Philosophic, but they can all get something out of education in their own way.

However, a word of caution here. A big part of "modern science" includes areas where the ability to abstract and model formally is essential - the sort of thing that algebra and formal logic classes are useful for getting you started on. The hard part here is not the logic, but the level of abstraction involved. (Kids can reason logically just fine in domains they have interest and knowledge/experience in - to see this, just ask a 6-year old if a tyrannosaurus ever fought a triceratops.)

The subjects that need this abstraction include programming/comp sci for sure, most jobs with "data" or "machine learning" in the name, mathematics at university level, quant finance, and a lot of engineering. It's not a perfect overlap with STEM but it's close enough. The problem is to most people - even quite a few Ravenclaws (especially primaries), I'd guess - this is a profoundly unnatural and inhuman way of thinking about things. It can be learned and trained, but it's really hard to motivate. (The people who are naturally inclined to this are not a perfect overlap with autistic people, but again, close enough.) Why water in a pond in winter ends up freezing at the surface but stays around 4 degrees Celsius further down much longer, is a question with a lot of science behind it that's comparatively easy to make interesting. The scope of a variable in a recursive algorithm, not so much.

3.

And finally, a political grumble. The summary of The Core on the amazon page you linked to includes a lot of good arguments ("Without knowing the multiplication tables, children can't advance to algebra.", "Most curricula today follow a haphazard sampling of topics"). But it also dips its toe into tribalism by accusing these haphazard curricula of "a focus on political correctness instead of teaching students how to study". (I guess this was written before everyone was saying "woke".) To me, apart from being tribal, that misses the point of why I'm not on team "progressive". The problem for me is the "they don't teach students how to study" part. The focus on promoting some form of justice and equality - that's one of the things they get right! (At least in principle. There is no shortage of examples of cringeworthy bad implementations of this idea in practice.) Whenever someone tries to appeal to a conservative audience by saying that schooling today is "too much of a mess, and too woke", those are two separate dimensions. If you only focus on the second one, whatever your views on social justice, you won't build a better system - you'll just have a different kind of mess centered around the Bible or something.

Whether this problem is in the book or just in the review, I don't know - I haven't read the book yet but I'm going to buy a copy. But it's again a question of separating out the "why" from the "how" - whether you want to make your students become patriotic conservative citizens or anarchist progressive internationalists, might determine what content you put in your curriculum, but that's still a separate dimension from how you make your school engaging. If we could only treat the second question as a non-partisan one, we could get so much done.