Note: I seem to have misplaced my big fat notebook in which I’ve been making outlines of these patterns. While I’m searching for it, enjoy this out-of-order post!

(Oh, and by the way, if you come across a faux-leather red three-ringed A5 dot-grid notebook with “If you find this notebook FOR THE LOVE OF GOD PLEASE RETURN IT TO [phone number]”, please shoot me a text.1)

1. A problem

Modern evolutionary biology is very clear: plants aren’t just “technically” alive, they’re alive alive — just as animate as animals. Yet when we study them in school, we treat them more like rocks: to be categorized, diagramed, and ignored.

2. Basic plan

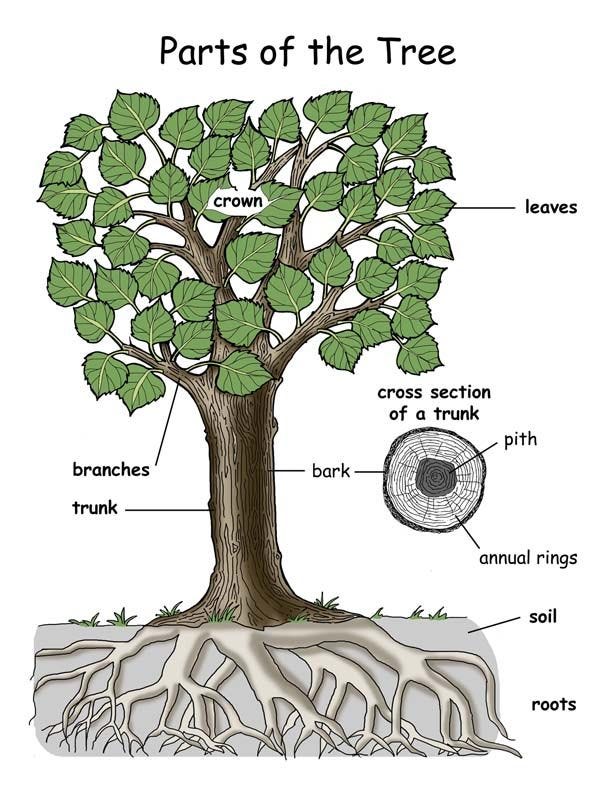

Starting in kindergarten, lead kids into close, multi-sense observation of one nearby tree. Pile up details. Soon, add on another tree — a rather different one — and call attention to the ways they differ. Begin to wonder why they have these differences.

After this, look up the basic facts: the genus and species, how long they live, where they come from, what they need to thrive. Gradually come to understand the two trees as actual organisms with actual goals — and see every trait they have as an ingenious way to achieve them.

Continue to watch them over seasons and years.

3. What you might see

Small groups of students crouched around a tree, feeling its bark, drawing its roots, collecting its flowers and seeds, describing its silhouette, crushing and smelling one of its leaves. Kids discussing what a proper name for each tree is, and them beginning to imagine each tree as an individual, the way they might see a cat, a goldfish, or a hermit crab.

4. Why?

The Scientific Revolution made us smart, but it also made us stupid.

Education still labors under a pre-Darwinian scientific worldview that was, in at least one key respect, less accurate than the worldview it cleared away: we talk about plants as if they’re objects.

For a long time we did the same with animals — witness how the philosopher–scientist René Descartes treated animals as mere clockworks devoid of feeling, or how the psychologist B.F. Skinner treated rats as perfectly-trainable machines, deriding as “unscientific” any talk of their internal lives.

Thinking about animals this way now seems ridiculous, but we do the same thing with plants. And this despite what we’ve learned from Darwin: that the elm tree on your lawn is literal family — something like your seventy-millionth cousin.2

You are kin to all living things. This seems to be intuited in animism — the worldview that understands that the natural world is filled with persons. And this intuition seems to have been reflected in the writings of some of our greatest souls. The authors of the Hindu Upanishads talk about the interconnectedness of all being. The Muslim poet Rumi wrote —

I died as a mineral and became a plant, I died as a plant and rose to animal, I died as an animal and I was Man. Why should I fear? When was I less by dying?

And of course the Christian monk St. Francis referred to the birds as “sisters”, and a wolf as “brother”.3

Meanwhile, in school, we teach kids where a frog’s gallbladder is.4 How far we’ve fallen.

5. Egan’s insight

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

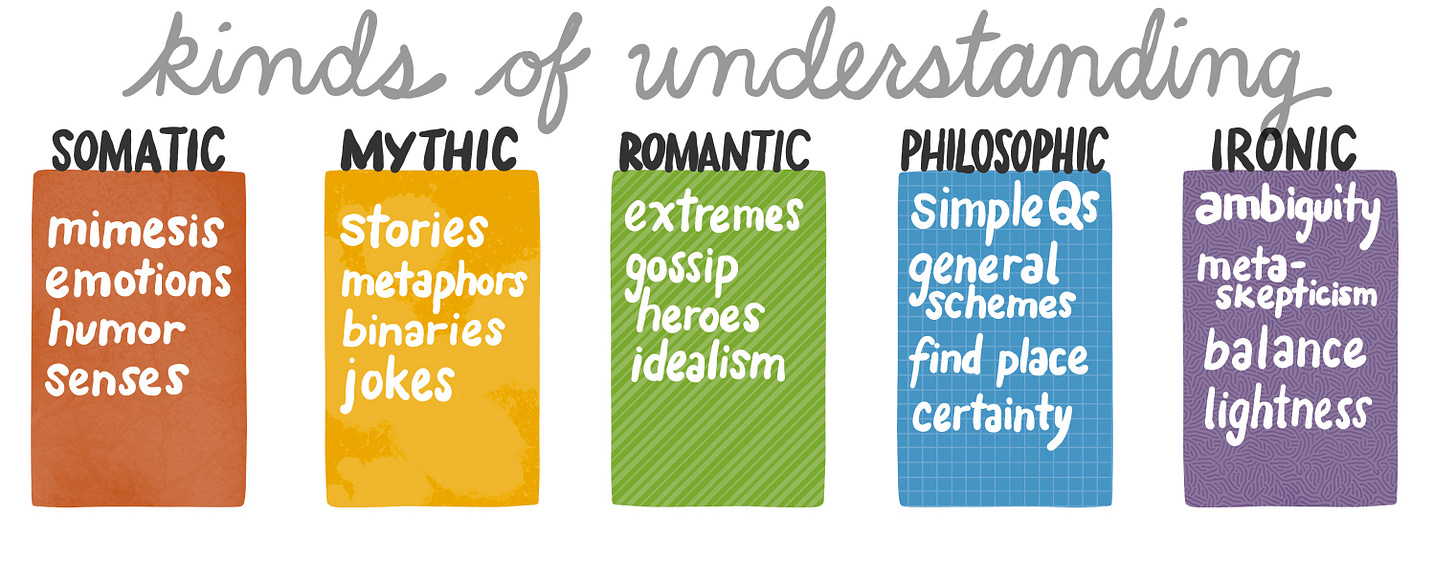

This might actually be a bit contentious, but I think the lion’s share of this is done by tapping into an underexplored aspect of SOMATIC (🤸♀️) understanding.

Don’t be confused by that title — for Egan, “somatic understanding” doesn’t just mean “stuff I can do with my body”, it includes “all the human ways of understanding the world that existed before we developed speech”. It includes all our knowledge of evolutionary psychology, too.5 And what seems obvious is that we recognize animate things as special: watch a one-year-old ignore a stuffed animal to stare at a cat. Heck, this goes beyond us — watch a cat ignore a doll to stare at a baby!

That’s all to say that what we want to do is trigger kids to 🤸♀️RECOGNIZE PERSONS.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Animism is silly; plants aren’t people.

Terms are hard, and the definitions that we’ve got were created back before the 20th century explosion in understanding botany. I’ll delineate a few other options below.

I. I.: Fine, for the moment I’ll pretend plants secretly ARE people. Why don’t kids see this, if “recognizing people” is an automatic brain thing?

Plants move toooooooo sloooooooowly for our brains to notice.6 So to get kids to recognize them as “persons”, we have to go deep into plants, engaging their imaginations, learning a lot. For that, tools from some other kinds of understanding are helpful. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

We can have kids write 🧙♂️LISTS of various aspects of their tree — “Textures” and “Colors” and “Things on the Bark” and “Things that Eat Them” and so forth. We can tell a life 🧙♂️STORY about a different tree.

We can also tell them the 🦹♂️GOSSIP about the scientists (like Darwin) who discovered that plants do act as if they have agency, and later help them enter the 👩🔬DEBATE as to whether plants actually have subjective experience.

Throughout all this, though, we want to be priming the pump by helping students make an 🤸♀️EMOTIONAL ATTACHMENT to their particular tree.

6. This might be especially useful for…

There’s a certain kind of kid who naturally feels affection for living things, and they’ll fall into this immediately. But I bet that even more benefit will go to the sort of kid who’s cut off from the natural world — the sort of kid who thinks that milk comes from the grocery store.

As kids spend less and less time outside, the number of those kids only grows.

7. Critical questions

Q: Okay, back to this “plants are people” thing. No. They’re. Not. Animism is cute and all, but it’s really important to get a definition like this right. No “woo” allowed in science class!

Hard agree! But — what does “person” mean?

It isn’t the same as “human being” — we say that Chewbacca and Spock and Bugs Bunny are people. (Moreover, we typically say that a decaying corpse is not a person.) The origin of the word person, actually, meant something like “a character in a play”, and its first use beyond that wasn’t to describe humans, but the idea of God — it was adopted by the Christians to be used in their debates over the Trinity. (Everyone could agree that God the Father is a person, but no one thought him a human.)

Wikipedia’s short article on “person” states the consensus well: a person is something that can reason, is conscious, has morals, and has relationships with others. And kids instinctively do perceive pets like gerbils and parrots and axolotls as having all of those.

Q: Yeah — trees can’t do any of that!

Well, they might, and they might not. It turns out that the study of plant intelligence is an exploding discipline right now. One fun thing: when you take a bite out of an apple, why does it turn brown?

Q: …oxidation?

Nope — the apple thinks it’s under attack, assumes it’s being attacked by micro-organisms, and sends out melanin molecules to defend. An apple is alive, and knows when you’re eating it.

Q: Are you saying it can feel pain?

It very probably can’t! An apple can’t repair itself, so feeling pain wouldn’t really be helpful.7 But their skin has photoreceptors, and the apple can see (or “see”) light — which is part of why, when apple producers are storing them, they typically do so in the dark.

Q: Fascinating! But why are we talking about pain?

Sorry, lost the thread there. I’ve found that some of the people who push back against calling plants “smart” change their minds when they find out some basic facts about fruit that they didn’t learn in school… because in school, they learned about plants as objects!

Q: Ah. Consider me ¼ won over. In the meantime, I’m still uncomfortable with the word “person”.

No prob. The word isn’t important in itself; what we want is to open ourselves up to perceiving trees as they actually are.

Here are some other words that might do that —

Option A: Trees are “organisms”: they’re living beings.

PRO: no one’s gonna object

CON: doesn’t get us very far to pushing students out of their old assumptions

Option B: Trees are “subjects”, not “objects”: entities with their own perspectives and experiences.

PRO: implies they actually experience the world, and nudges us to imagine “what’s it like to be a tree?”

CON: this is actually the hardest thing to prove — famously, it’s technically impossible for you to philosophically prove that anyone you know has subjective experience

Option C: Trees are “agents”: they make decisions and act on their surroundings.

PRO: technically correct, gives us most of what we want

CON: sounds like we’re saying trees work for the State Department and get into tussles with old members of the KGB

Option D: Trees are “slow-motion animals”: we should copy over all our assumptions about animals to plants.

PRO: instantaneously brings us exactly where we want to be

CON: technically false (and also trees are weirder than animals in other ways)

Q: How often do you suggest a classroom does this?

Somewhere between every day and every two weeks. Less in the winter — though it’s super important to go at least a few times, to see what your tree has to contend with in the cold.

Think this is too woo? Or would you like to suggest some specific activities students can do for this? Frankly, WE WOULD LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT IT. Become a paid subscriber and join in the comments conversation.

8. Classroom setup

Well, of course it’d be nice to have access to some trees.

9. Who else is doing this?

A lot of people are talking about this.

I’m developing this mostly from my readings in the new science of plants. Michael Pollan’s 2013 New Yorker essay “The Intelligent Plant” rocked my world… by making me realize I had always perceived trees as only technically “alive”. Since then I’ve read Daniel Chamovitz’s What a Plant Knows and Stefan Mancuso’s The Revolutionary Genius of Plants.

The person who’s doing this the most is probably Tristan Gooley. To be fair, Gooley might be the person who does most things the most: he’s an adventurer who’s climbed mountains, flown and sailed across the Atlantic Ocean by himself, and has learned how to read nature like a book.

I haven’t read his recent book How to Read a Tree yet…

…but I have read the Psmith’s amazing review of it. (h/t to

for reminding me of this!)How could we start small, now?

Pick a tree, and start writing a list of everything you notice about it. Read the Psmith’s review of Gooley’s book — aloud to your kids, if they’re up for it — and have your eyes opened to what you were missing!

10. Related patterns

Once you understand a tree from the inside, the whole array of Local Trees° becomes fascinating. This is parallel to other patterns like Learning in Depth° (March 6), Site Grokking° (April 10), and Knowing a Meal°, which all fixate on one thing for a long time.

Afterword:

I’ve upturned the house in search of the lost notebook into which dozens of hours has been spent outlining future patterns: no luck. Next step is to offer my kids cold hard cash for finding it. Will keep you posted…

And you probably think I’m joking about the cover!

You can see how I brilliantly calculated that got ChatGPT to calculate that for me here.

And, in his famous Canticle of the Creatures, the Sun, the Moon, the wind, the water, fire, the Earth, and death. I bring this up only because I don’t want to suggest that people like Francis were Darwin before Darwin — they were casting a wider net.

It’s inside the frog.

Are there still circles in which mentioning “evolutionary psychology” sets off warning bells? So be it. If you’d like to interpret this as “all the good things from evolutionary psychology that I don’t hate”, then, cool, run with that.

Except for Venus Flytraps, the Whomping Willow, and Audrey II.

Similarly ants: an ant is a throwaway piece of an ant colony, and there’s no way to heal one that has its leg bitten off, so “feel horrible, horrible pain” probably wouldn’t be useful, evolutionarily — and indeed ants seem to barely notice when they lose a limb. Crabs, on the other hand, do…

Add in an excerpt from How to Read a Tree, which helps you look at a tree and think in its timescale and see marks of its history in its shape: https://www.thepsmiths.com/p/review-how-to-read-a-tree-by-tristan

I really love this idea!

The late Oliver Rackham (obituary: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/feb/20/oliver-rackham) - the person who coined and defined the UK-specific term "Ancient Woodland" that you hear in pretty much any debate about conservation over here - certainly knew how to read trees; his work I've read on how trees populated the British Isles at the end of the last Ice Age certainly has you think of different species as "peoples" in the widest sense, setting up their own provinces and colonies.

(before someone replies "username checks out", yes that's my favourite tree)