Note: Book club on Saturday! Basically: what would the world’s most wonderful history curriculum look like? Info at the bottom.

1. A problem

To properly understand most things, you have to get outside. Almost all of schooling happens inside, but so many of the academic disciplines (zoology, botany, geology, paleontology, and even history) describe the world outside. We’re not actually teaching our kids if we’re not connecting their minds to the real world beyond the classroom.

2. Basic plan

Pick a nearby natural feature, and study it in depth for three years. A creek or river will do, or a gully or gorge, or a hill or a mountain. Spend a year on its prehistory, a year on its present ecology, and a year on its human history. Angle all of this toward an ambitious presentation whose form is picked in advance — a video, say, or a book, or a mural. If you’re in a school, have the entire school work together toward this.

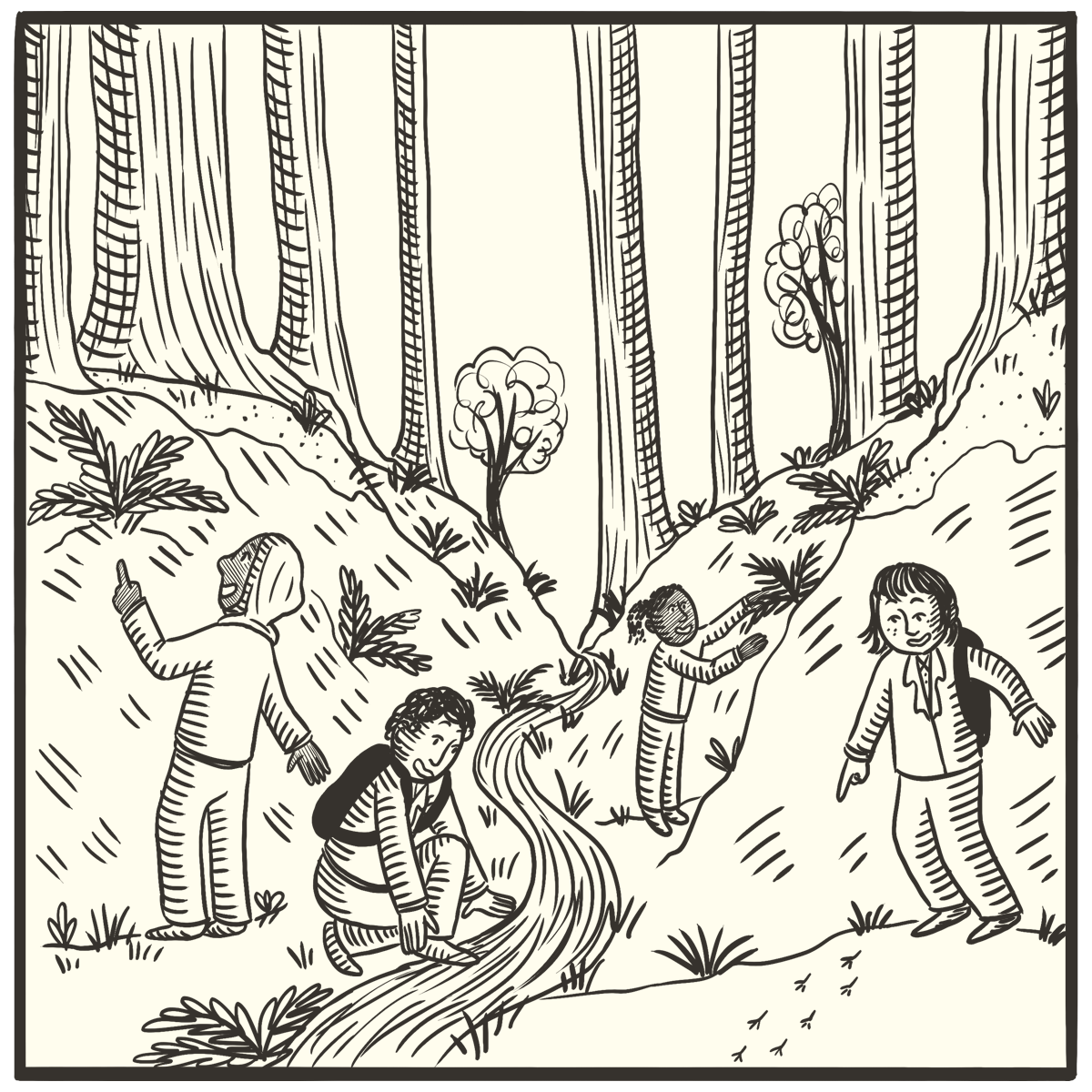

3. What you might see

Kids visiting a place often and growing to fall in love with it. Students drawing it, mapping it, cataloging its species and drawing the food webs that connect them. Teachers presenting the deep history of the place. Parents and members of the community being drawn up into lust for a specific place.

4. Why?

Every spot of the natural world is a door to the big picture of life, the Universe, and Everything; a single site holds more complexity than anything that most schools ask kids to learn — and using Egan’s paradigm, we can guide kids toward understanding it. Yet education usually has nothing to say about the world immediately around us; the walls of a school might as well be a moat. This is perverse!

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

The natural world was humanity’s first teacher. And it’s so interesting — every single place is a site of threat and beauty, death and life, rot and beauty. Our modern academic subjects rose out of the attempt to make sense of what’s going on.

We see this on the personal level, too. How many of us haven’t had a small outdoor place that we’ve fallen in love with?

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

Thoroughly. Like a Learning in Depth° topic (and like the whole Big Spiral History° and Big Spiral Science° patterns) this is a backbone to helping explore all the ways of understanding.

6. This might be especially useful for…

Anyone who’s ever watched a documentary about one of our great naturalists — someone like Alexander von Humboldt, John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, Rachel Carson, David Attenborough, E. O. Wilson — and felt a longing to immerse themselves so completely in the world.

7. Critical questions

Q: THREE YEARS?

Yup. But it doesn’t seem so long if you break it up.

Spend one year in prehistory, and work to imagine the 4.5 billion year story of the place, from the cooling of the crust onwards. Spend a year on the ecology, working to hold in your mind all the types of animals and plants (and fungi and bacteria) that are important in the place. Finally, spend a year understanding the human experience of the site, from what we understand about the first inhabitants of the area to the economics, laws, and anthropology of the place in the present day.

Q: Do they need to be in that order?

Nope!

Q: …could we spend more than three years?

In Whole School Projects, Kieran Egan suggests that three years might be the perfect amount of time: so long that it’s insanely ambitious, and just short enough that it doesn’t get dull. (He also suggests that the fourth year be dedicated to rest, and planning out the next site.)

You’ve got another question, don’t you? Subscribe, and join in the conversation in the comments.

8. Physical space

At home

For homeschoolers (or any parent doing this with their kids, say, on the weekends), small is beautiful. You’ll probably want to choose someplace you can comfortably walk or bike to. (If you’re in a place that’s totally denuded of any natural history, get creative.) You’ll want to make sure that it’s legal — or at least not egregiously illegal — for you to be there.

In a classroom

For a school, bigger is better. You’ll want to choose someplace that can have an entire classroom (or more) in it at once. It’d be amazing if this space is on school property (or immediately adjacent), but it’s okay if it takes a short bus ride to get to.

9. Who else is doing this?

An admission — I’m taking one of Egan’s patterns here, and flipping its focus. For Egan, the glory of a “Whole School Project” was that it provided an opportunity to knit a school together and make it a community; that it be a natural spot was secondary. (One of the schools he worked with in China made creating a garden the focus of their Whole School Project; one of the schools he worked with in England made a local castle their focus.)

But if I’m understanding the story right, the original idea for this actually burbled out the work of the brilliant educators in the Egan charter school outside of Portland, Oregon, who determined that it’d be a delight to put the tools of Egan education to use in understanding the Columbia River Gorge that was close by. When I visited, I believe they were just finishing their year on prehistory; kids had made books that told the 4.5 billion year history of the Gorge, and had transformed the whole school into a presentation. (The photos on this post are all from there.)

How might we start small, now?

If you’re in a school, buy a copy of Egan’s Whole School Projects: Engaging Imaginations Through Interdisciplinary Inquiry; it’s short, and gives direct instructions on how to build the buy-in to start.

If you’re a parent, skip the book and go to Google Earth to spy some nearby spots you might pick. (A good place to start: where’s the nearest running water?)

10. Related patterns

This would be a great way to bring together Local Trees°, Local Birds°, Local Bugs, and Local Flowers°. It’s also a great opportunity to practice Drawing Maps°. Because “wait, are we really allowed to be here, and what aren’t we allowed to do here?” are natural questions to ask, it’s a way to make Everyone Learns Law° relevant.

The walks that Gillian Judson (one of Egan’s students and long-term collaborators — and a co-author of Whole School Projects) lays out in her book A Walking Curriculum: Evoking Wonder And Developing Sense of Place (which we’ll explore more of in A Walking Curriculum°) are a great way to begin to really know a place in all its complexity.

Afterword:

Perhaps you noticed this pattern is shorter than the others? Part of the reason is that I (as predicted!) fell behind when I was on my eclipse vacation, and am trying to catch up. But another part is that I’ve heard from some folks that they have a hard time reading the pattern language posts because they’re really long. (I commissioned a poll recently which said that the overwhelming majority of people liked how long they were… but only recently realized that there might be some selection bias there.) Anyhoo, two birds with one stone.

Also, to make it easier to skim future patterns, I’ll try to boldface the most important sentence per section. Hooray!

Oh, hey — “book” club this Saturday afternoon (3pm Eastern Daylight / 12pm Pacific Daylight). Wow, I’m bad at keeping up at these things! We’ll be discussing “Big Spiral History”. The reading will be two past patterns — Spiral History° and Big History° — if you’d like to do extra reading, here’s the paper I presented on it at the inaugural International Big History Association conference. I’ll post the Zoom link the hour before, for paying subscribers.

Arg. I missed today's book club (my day was thrown off when I found a sweet lost dog standing in the middle of a country road this morning ... and my day went sideways after that...). I know, sounds like the set up for a country song (and I love country music!)

Anyhow, I was really looking forward to this discussion because I wanted to pose a question/get feedback on a specific topics, so I'll throw it out here since I missed the real time option....

Several years ago my favorite librarian at our public library introduced me to the concept that there are different types of readers (character, plot, and I think the 3rd she mentioned was genre, but I could be wrong here) and she said that if you know what type of reader a reader is, it's far easier for someone to make recommendations because you know what the hook is for them. (Not all Harry Potter fans are alike!)

Anyhow, I was reflecting the other day about how growing up and all the way through college, history was by far my least favorite class. I did just fine in the class, but it was more just something I took because I had to (I satisfied the absolute minimum history requirement in high school and didn't take a single history class in college.). Fast forward to today and 90% of the books I read for pleasure could be classified as history books and I LOVE history.

I am now homeschooling a middle schooler who has expressed zero interest in history and I got to wondering, perhaps are there different ways learners engage with history (like the different types of readers) and that maybe with this knowledge we might approach teaching history differently with different types of learners? My working hypothesis is that there are different types of meaning people can find in history. But I'm not sure what those categories might be? Thoughts?

This appeals to me in part because we already have a robust routine of visiting the same nature spots over and over. And because I've always struggled to hold the changes that have happened to the whole planet throughout big history in my mind; starting by understanding it locally seems simpler!

The spot I'm leaning towards is not the best bike ride due to traffic, but is a very short drive. Realistically we could easily go there once or twice a month. It's been a pear orchard and a golf course and for the past few decades it's been a natural area with efforts to restore habitats. The volunteers are helpful and enthusiastic. The space is small enough that my kids know it (somatically?) very well already, but it's larger and more wild than anything closer. Alternatively we could stick with a place we could walk or bike to, but that's city parks or a gravel path along a flood prevention channel. Or, we could go to a county park that is awesome, but probably a once a month destination if that. Decisions decisions.