Note: There’s an announcement at the end of this post. (Also, for reasons you’ll see, the comments section is open to all subscribers.)

1. A problem

The American Impressionist painter Robert Henri said the quiet part loud —

Real students go out of beaten paths, whether beaten by themselves or by others, and have adventure with the unknown.

There are few students in the schools. They are rare anywhere. And yet it is only the student who dares to take a chance, who has a real good time in life.

To be a student is to be changed by what you learn — to fall in and out of love with it, to start to see everything through what you’re studying, to slowly make your way to the edge of what people know.

We have so many schools, and so few real students. And this is because we don’t have a way to help students go deep into what they’re studying.

2. Basic plan

At the end of the week of 1st grade, at a ceremony attended by family members, Sara and her classmates each receive a topic that they will study throughout their schooling. There is much excitement as the students prepare to discover what they will become experts in. Sara walks on the stage in her turn, and the teacher hands her a folder. Inside is a small, colorful tile on which her topic is written, along with a picture of the topic and her name.

Sara announces to the audience that she is to learn about apples for the next 12 years. The tile is added to a wall of such tiles in the school.

So narrates Kieran Egan in his (short) article “Learning in Depth”,1 published sixteen years ago in Educational Leadership. In fact, I recommend just reading it now, especially if this idea sounds bat-crap insane to you:

3. What you might see

A second grader who’s been given the topic of “rocks” asking relatives to share weird stones they find, so they can collect all the kinds.

A fourth grader with the topic of “volcanoes” looking on a map to find the nearest one (alas, probably extinct), and politely requesting their parents to steer the next family vacation in that direction so they can observe the thing directly to answer some questions that books don’t ask.

A sixth grader studying “eggs”, dissecting a chicken egg, and puzzling mightily over what that bungee-cord-shaped doohickey actually is, and recognizing that holy crap humans have egg whites too.2

An eighth grader given “wood” able to identify different woods blindfolded (by touch, heft, and smell), able to identify them under a microscope, and able to tell you why they evolved like that.

A tenth grader who’s studying “whales” learning what the biggest threats to the Vaquita are, and triple-checking the grammar in her emails to leaders in the fishing industry.

A twelfth grader who’s been studying “colors” for a dozen years now delighting in the reactions they get when they say their favorite color is “puce”, expounding on why most people assume it’s a type of yellow, and carefully explaining why, according to our modern understanding of light, puce is one of the colors that literally does not exist.3

4. Why?

According to William Butler Yeats Socrates Plutarch the Internet,4

WHELP IT’S HARD TO SAY IT BETTER THAN THAT.

But it’s one thing to share a meme on Facebook, and another to create the actual experience for a human being. And as Egan was prone to pointing out, none of the schools we have regularly succeed at doing this.

Educational Traditionalism and Educational Progressivism both talk a big game, but none of their schools bring the goods. Centuries of educational philosophies have fought with one another, but only seldom has anyone acknowledged that our society lacks the technology to create real “students”.

Schools are, instead, places where we play-act lighting fires.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

In my experience, you find something like this in almost everyone who’s thought of as having genius.

We sometimes think of intelligence as an inborn trait of an individual, and there’s definitely something to this. (IQ correlates much more to genes than to life experience, after all.) But I think that what we call “genius” is more a product of the dance between a person and the topics that obsess them.

Early on in their life, a future brilliant person often becomes interested in some random topic; they probe it for years. It’s through this dance that they connect with real scholarship and become skeptical of their first impressions. They learn that everything connects to everything, and become convinced that many things that other people call dull are actually fascinating.

The thing is, this usually happens haphazardly.

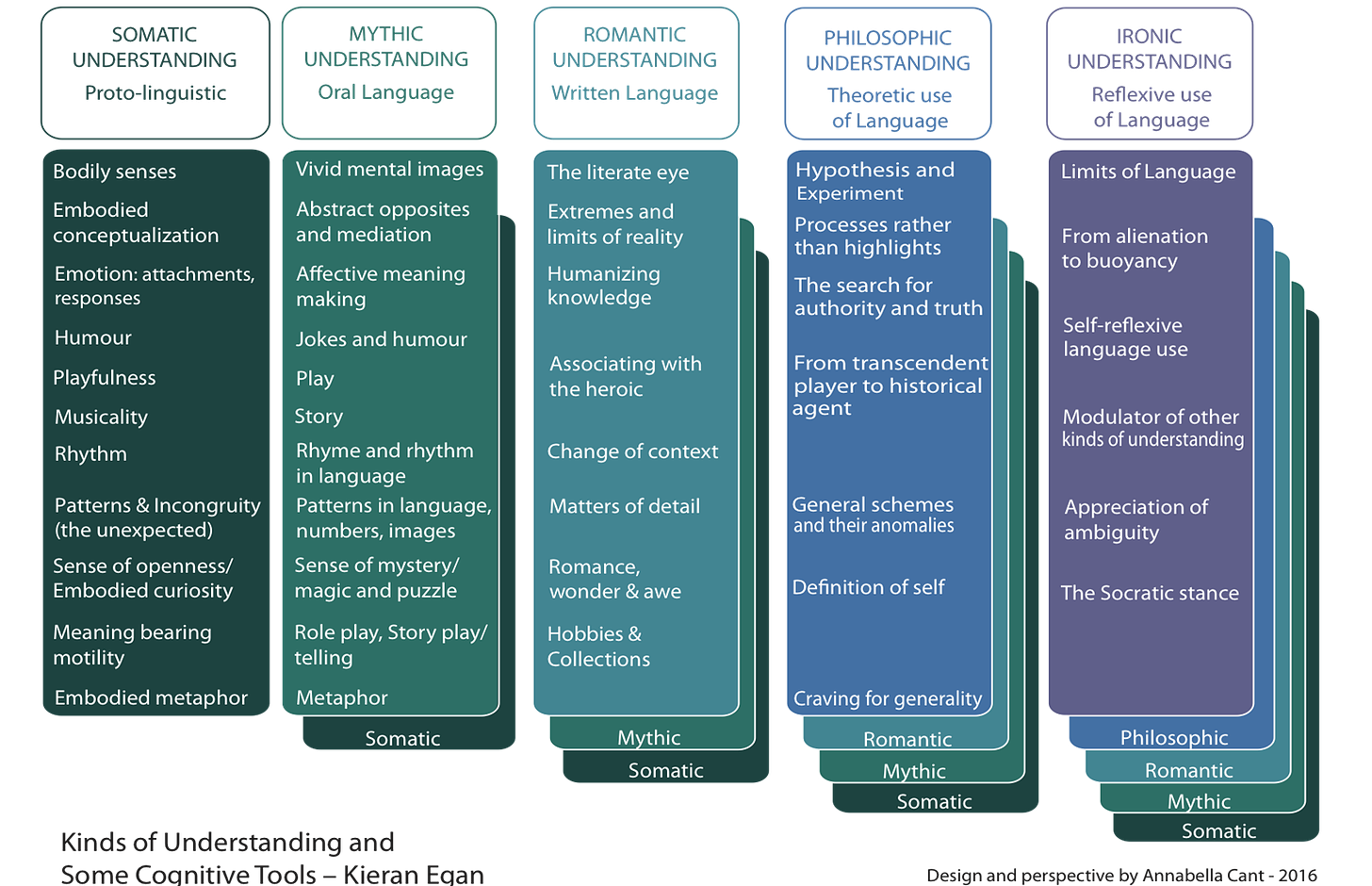

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

Efficiently.

Learning in Depth (the cool kids call it “LiD”, and I suppose we can, too) isn’t like most of the other kinds of tools in our pattern language — it’s a super-tool. Its explicit purpose is to help people master all the tools, so they cultivate all the kinds of understanding.

In LiD, kids are given small nudges from their teacher to use these tools to go another step deeper into their assigned topic. From this, they gradually hone all five kinds of understanding. (What do we mean by “kinds of understanding”, again?)

6. This might be especially useful for…

…people who want to develop high-end research skills.

When you start a new topic, it’s enough to ping ChatGPT (or read Simple English Wikipedia). It’s only when you go deep into a project that you have to push into real research — raiding your library for books, skimming scores of essays and articles, imbibing zillions of YouTube videos. Once there, you’ll find disagreement, and figure out what’s trustworthy and what’s not.

…people who want to sniff out truth.

One reason online misinformation is such a problem, I suspect, is that there are too many things to learn about, and people are just not accustomed to doing this anymore. By diving to the bottom of one topic, you learn what it takes to secure knowledge about any topic.

…people who want to be more curious in general.

For all of the downsides of Philosophic understanding, one of its benefits is that it makes everything interesting again, because everything connects to everything, and a new discovery about the smallest, most inconsequential thing might threaten to upend how you see everything.5

…people who want to forge connections with people very unlike themselves

Cultures connect strangers into a whole, but this can make relationships between people in different cultures hard. LiD can play a role in breaking this down, by giving kids a shared interest they can use to connect deeply with someone who’s otherwise very different than them.

Imagine you had spent a decade falling in love with “mollusks”, and were put in a room with someone whose politics, values, and cultural assumptions were very little like yours. You’re on edge… until you find out that she studied mollusks, too!

The possibilities for LiD to help rub away hostilities between cliques, or gangs, or even opposing national groups seem… intriguing.

…people who want information to become wisdom.

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?– T. S. Eliot

Wisdom is perspective. (Literally, in English: wis is the same as the vis in “vision”.) To be wise requires seeing the big picture. But we can only really see the big picture from small specifics. By helping people focus on one thing over a long period of time, LiD lets us see the big picture through a small specific.

7. Critical questions

Q: I suppose I find this interesting, but… twelve years?

The length is load-bearing: it gives you time to change, so that your understanding of the topic has time to change.

When talking about LiD, Egan was fond of saying

Each student, by the end of his or her schooling,

would know as much about that topic

as almost anyone on earth.

But let’s go beyond just the raw quantity of information you could imagine learning about, say, “whales & dolphins”, after a dozen years. Imagine the quality: how rich your feelings would be toward them. Through the ups and downs of adolescence, through bouts of bullying and your grandma getting cancer and your parents splitting up, you’ll always have been able to count on dolphins.

Q: How much time should this take, as you go on?

If one is doing this over multiple years, just 30 minutes or so of class time could be allocated to this each week. But, of course, students can invest more time if and when they want. (Among other virtues, it’s an easy thing for a student to jump back into when they, say, finish early on a test, and are looking for something else to do.)

Q: I’m imagining a teacher having to stay on top of 25 topics — good gravy. This would be MUCH too much work for teachers.

Another virtue of LiD is its simplicity — it can be fairly student-led. Egan suggests a 15-minute check-in meeting with an adult (a teacher, a school librarian, or a classroom volunteer) perhaps once or twice a month.

But to make this even simpler and easier for teachers is to develop a simple curriculum that can take students through the different tools by giving them a few quick “challenges” a week.

Q: Should it be graded?

No.

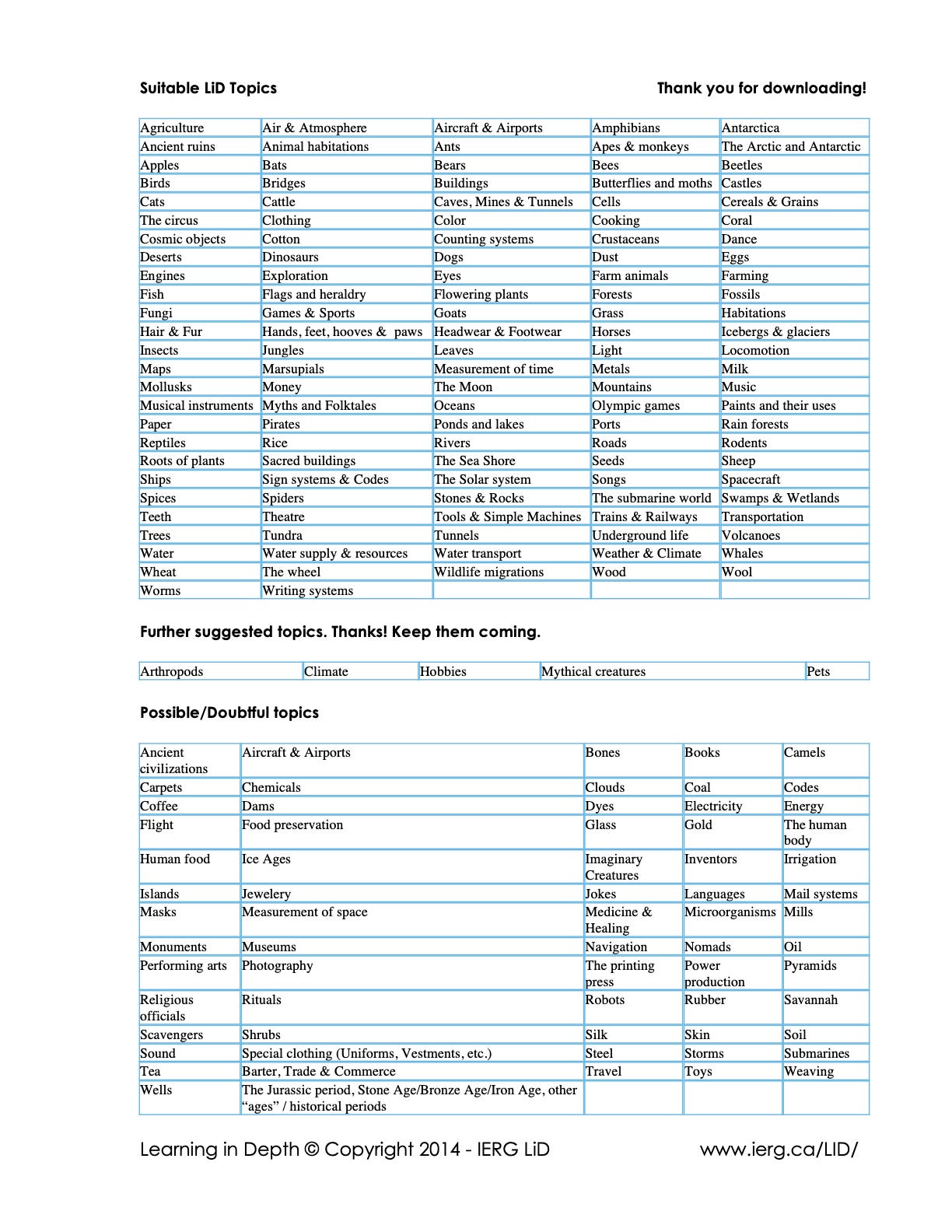

Q: Beyond “apples”, what topics are we talking about?

Take a look at the list of 127 suitable topics (and 80-odd unsuitable topics) Egan and his collaborators worked hard to sift out:

Q: What’s special about those topics?

A whole bunch. Read chapter 4 of Egan’s book Learning in Depth: A Simple Innovation that can Transform Schooling, in which he expands on that essay. In short, though: there are some topics that don’t really work to learn about over all the kinds of understanding. (No matter how interested you are in Pokémon, it’s hard to develop Somatic understanding of them.) Mostly they’re too narrow or too broad.6

Q: Okay, I’m looking at that list and I’m seeing “dust”. “Dust” is not interesting. No one could study “dust” for twelve years and live to tell the tale.

[Sighs.] Let’s do this —

Dust feeds rainforests — the phosphorus-rich dust of the Sahara Desert is carried across the Atlantic to fertilize the Amazon

Pure water can’t actually freeze at 0º Celsius — it needs dust to do that. Because of this, a single piece of dust is at the center of every snowflake

The dust in your house has a lot of skin cells in it. Okay, you knew that — how about this: dust blows around the world — the dust in your living room is made up of, in part, the skin of people living on the other side of the world. (One way scientists figure out where wind blows is by looking at local dust)

Yes, I could do this all day. And, honestly, for twelve years! Because behind this pattern is the recognition that everything is interesting.

Q: Just one topic, though! Students will become bored with it. Let’s let them change each year.

Almost a decade ago I visited an elementary school that was doing Learning in Depth, and got to talk to students who’d been working with their topics for four or five years. I was surprised to see that they loved their topics, all the more because they were theirs.

As they went on, they were making the topics their own. A kid7 who had been given “rice” but was obsessed with dinosaurs would turn his topic back to dinosaurs:

did dinosaurs eat rice? (no)

did rice even exist when the dinosaurs lived? (no!)

wait, why didn’t it exist? (it hadn’t evolved yet)

how did rice evolve? (from the first flowering plants in the Cretaceous)

what made flowers evolve? (beetles and ants and bees)

did any dinosaurs co-evolve like that?

Again: everything is interesting, they just seem boring before we break through the crust. And a LiD project is a way to break way, way through the crust.

Q: What about in an extreme case, where a kid resolutely hates their topic for a long time?

Obviously, certain allowances should be made for extreme cases.

Q: But why shouldn’t students CHOOSE the topic in the first place?

Not to get all arranged-marriage-y (!), but this feels like a basic psychological principle: commitment provides focus, and what’s chosen can be unchosen.

That’s to say, in order to devote our attention to something, we need to be committed to it; we can’t always be playing with the idea that we should bail. And if we had chosen something in the first place, and we get bored, we might worry that we had made a mistake in choosing it in the first place.

When I visited that school, one girl shocked me with her self-understanding. She told me that she went through phases of being agog and being a little bored, and that this used to worry her — but now she’d come to understand it as a natural cycle.

Huh, I thought: Learning in Depth makes kids old souls.

Q: What bothers me is the RANDOMNESS of the matching. Surely some kids feel more of a pull toward trains, or towards cats, or towards cosmic objects.

In Egan’s book that expands on his initial essay, Learning in Depth: A Simple Innovation that can Transform Schooling, Egan acknowledges that this is true, and accepts as “an interesting compromise” what one teacher did: showed her class the list of 127 topics, had them pick three they were most interested in, and then chose from those randomly.

When my wife and I did a version of Learning in Depth — a year-long “Zoology in Depth” program at the elementary school we taught at — we did this, except we also asked students to pick one topic they would hate to get. Students got nervous when they saw us write that topic on a card, alongside the three cards for the topics they hoped for. Then, in a small ceremony, we drew the cards from a hat… except we palmed the hated cards, so no one picked them, and everyone was thankful for what they got, and they all lived happily ever after.8

Anyhoo, I don’t actually think this is ideal, but it’s an option.

Q: This sounds a lot like “interest projects”. What’s the diff?

Well, it differs in the ways that make people uncomfortable with it: the topic is assigned somewhat randomly, and it’s worked on for multiple years.

(This should, by the way, make us more confident of LiD. “Interest projects” are the sort of educational innovation that sounds good but which — and I can say this with some authority after having worked in Progressivist education for a good long while — usually end up depressing everyone involved. Students’ projects are frequently slapped together at the last minute; a short conversation with the other students usually shows that their “understanding” of their “passion project” is an inch deep.)

The other way it’s different, though, is that it’s guided by the cognitive tools. In this, it’s Egan’s whole paradigm of education, jammed into its simplest, cutest, widdlest— aw man I can’t get the vaquita out of my head!

The vaquita above would like you to know that there are only around 10 of them left, and that the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society is working to save them. If your conscience isn’t distracted by that, and you’d like to support THIS attempt to help mend the world, become a paid subscriber!

8. Classroom setup

You know how in elementary school you were graded on making cool-looking-but-educationally-questionable projects like sourdough maps of Easter Island or dioramas of the benthic zone? Well, LiD is a great way to create visuals that really do capture advanced knowledge. So expect classrooms bedecked with gorgeous art.

9. Who else is doing this?

Of all of Kieran Egan’s ideas, LiD got the most traction. It’s still being used in a number of classrooms across the world. In the near future, I’d love to connect with some of the people working with it, and get their stories and advice.

How might we start small, now?

Read Egan’s short article, if you haven’t already. And then see the announcement at the end.

10. Related patterns

In some ways, LiD is in a class by itself. But there are a few other patterns that similarly take one boring-seeming topic and dive ridiculously in depth over the course of multiple years: Know a Tree°, Know a Site° (April 10), and Know a Meal°.

Announcement:

So: since writing the book review, a bunch of people have told me:

This sounds great! How can I use it to help my own kid / my own self become more brilliant and thoughtful and rational and imaginative and A REAL STUDENT?

My answer to this has been to explain that this is what I’m dedicating the rest of my life to doing, and things like “forging a new method of homeschooling” and “helping start a new kind of school” take time, blah blah blah.

They invariably respond:

But what can I do RIGHT NOW?

And my answer to that has been to mumble something, then try to distract them by sharing cool facts about the solar system.

Today I’m excited to announce:

This summer,9 you’re invited to join an intellectual adventure. Alessandro and I—

Q: Who’s Alessandro?

Oh my gosh, I keep mentioning him, but I haven’t formerly introduced him yet, have I? Alessandro Gelmi is one of the cleverest and most thoughtful people I know. His background is in philosophy, and he’s finishing up his PhD at Italy’s Università di Bolzano. He’s a globe-trotter, and a rising figure in the international Egan community. Right now he’s working with Italian teachers to bring Egan’s approach into their classrooms. Our monthly Zoom conversations about the world of ideas are scintillating.

This summer, Alessandro and I are creating a LiD intensive.

Q: What’s a LiD intensive?

If you sign up, you’ll get a topic. Then each week, for 10 weeks, three, four, or five simple and fun LiD challenges will be dropped into your inbox by a big hairy pterodactyl.

And once or twice a month, the whole group will meet for a Zoom with Alessandro to get guidance and share what’s happening.

Q: What’s the goal?

To push you beyond your current limits of understanding the world. To expand what “learning” means to you. To connect your emotions and intellect and perceptions to make you more educated, in the fullest sense of that word.

Q: LiD is designed to take more than a decade — is this possible in ten weeks?

We don’t know! This is an experiment. If you sign up, you’ll be a guinea pig.

Ultimately, our goal is to make it easy for teachers the world over to do LiD in their classrooms, and for the process to be joyous for students. If we can pull that off… we might be able to change education, everywhere.

This is the widdlest simplest iteration we can think of to build on. In startup terms, it’s the Minimum Viable Product. We’re treating this as a way to make mistakes, get your radically honest feedback, and make it better, fast.

Q: Will the topic be assigned to me, or will I get to choose it?

It’ll be your choice. (Getting data on this will be just one of the useful bits we hope to learn.)

Q: I’m interested in collecting and analyzing data for this.

Contact us.

Q: What sorts of understandings will you start with?

Mythic, and then expand out to the others.

Q: What ages is this for?

Kids & adults. Some of the latter challenges might be more challenging for kids under 12, but the bulk should be doable with some parental help.

If we get large contingents of kids and adults, we might split the Zooms into two groups.

Q: What’s the cost?

We’re still deciding this; it depends on how many challenges and Zoom meetings we plan. If you’re interested, click the button below to get our questionnaire. We’ll ask you what you’re particularly excited about — and will plan the details to fit what people most want.

Q: Will you repeat this in the future?

Who knows! Entrepreneurship is fun! Wheeee!

Q: I have more questions. SO MANY MORE QUESTIONS.

Wonderful — ask ‘em in the comments. (Comments for this post are open to all subscribers.)

How short? Shorter than this post. (And with oodles of evocative images.)

We just call it something different. (Hint: starts with “a”.)

Then they quote an enigmatic saying of Edmund Husserl, the 20th-century Austrian philosopher who founded the school of Phenomenology, and disappear in a puff of logic.

For me, lately, this has been Lagrangian mechanics: seeing that the angle which sunlight bends as it hits glass is every bit as weird as it had seemed to me, and discovering that one can mount a defense of Aristotelian physics based on it. (Shout-out to John Psmith for this.)

Also, um, some point you to pornography when you google them.

I’m totally making up this kid, but only because it’s been a long time, and I can’t remember all the specific conversations I had with them.

I’m telling you: good teaching is in the drama.

Or, if you’re south of the equator, “winter”.

I think the thing that resonates the most with me here is the random selection of a topic. Kids have such a poor understanding of how experience shapes their preference. They are under the impression that they can predict what will be boring to them. I think it’s total nonsense. It’s in the nature of the interesting aspects of things to be hidden. You can’t see what’s interesting about a thing before you start playing with it. The good stuff is always below the surface. You can’t see it. And if you only go into what you think you’ll enjoy, you never get to observe that you have no idea what will be interesting to you. You never get to learn how real learning is a real adventure, a real quest, with real surprises and real plot-twists. How I wish I could get my kids to grok that! Of course, this is quite in contrast with the follow-your-dream message they imbibe in the gallons from the surrounding culture. Tough sell.

I'm interested to know how LiD would have worked in the pre-internet world, which was presumably the one Egan designed it for. How would parents of average means in some small town got their child to be a world expert on apples?

I remember a time when, as a child, the extent of information available to me was what my parents and teachers knew, and what was in the papers and on TV when we watched it, and what books my town's library had. Sometimes we took a trip to the Big City and got to visit the bookshops and stock up on new sources of knowledge. What a different world where there's so much available online, for free - though getting wisdom out of mere information hasn't got that much easier.