1. A problem

Fate plays a cruel trick on the over-a-billion kids who learn English: the language doesn’t match the alphabet.

For idiosyncratic historical reasons,1 we write English with the Latin alphabet, which was [spoiler warning] made for Latin. Because of this, learning to read English is hard.

To wit, no Roman ever needed to use the two “th” sounds (as in therein and thwack), and so we have no letter for either. Ditto with the “sh” sound (as in shimmy), the ch sound (churlish), and the “ng” sound (as in dithering).2

And then there are our vowels. English has lots of “long” vowel sounds3 (as in make and see and food and make me seafood) which Latin lacked. Worse still, we have an unhealthy clump of dipthongs — vowel mash-ups like my and no and how.

Q: Wait, those are mash-ups?

Yeah, if English is your native language, you probably don’t even notice this.4 But say the word “my” slowly, and you’ll notice that it has two vowel sounds: mm-ah-ee. Ditto nn-oh-oo and hh-ah-oo.

Anyhow, these are all details to the big point: English spelling (and therefore reading) is a beast to learn, and part of that is because the language doesn’t fit the alphabet.

2. Basic plan

Introduce kids to other alphabets, so they can begin to see how languages can work — the better to understand their own.

3. What you might see

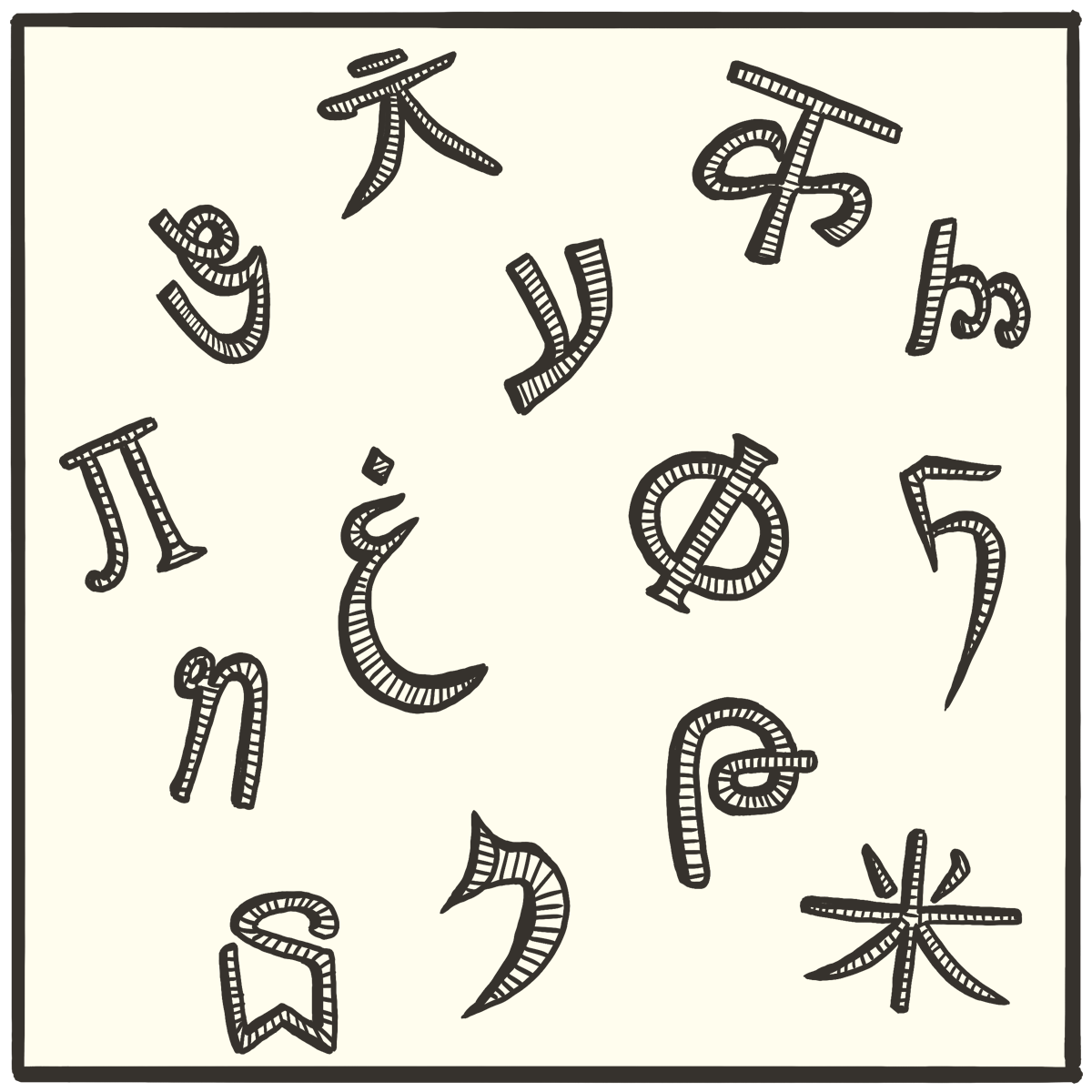

Weekly (or daily), a cryptic message appears on the wall written in a non-Latin script — say, Arabic, Cyrillic, Devanagari, Greek, Hangul (Korean), Hebrew, Katakana (Japanese), Pinyin, Tamil, Tengwar, Thai, or ancient Phoenician — and kids using all the tools they have to figure out what’s being written.

Kids who, on their own, are inspired to take up Arabic calligraphy, or pass notes to one another in Elvish.

4. Why?

Foreign cultures often feel more alien than they actually are; learning other alphabets is one way to break through the crust.

Q: But if that’s what you’d like to do, wouldn’t it be much more effective to actually learn the language?

Definitely, but as an alphabet is much much easier to learn, there’s more bang for your culture-vulture buck. (Perhaps it only provides 5% of the value of knowing a language? Still, it only takes 0.5% of the time.)

In any case, it’s also a great first step in actually learning a new language.

Q: But does Egan say anything about actually learning other languages?

Very much so! More on that anon.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Seeing into many different cultures — and recognizing how your own culture is “alien”, too — seems to have been one of the original sparks in what we now call critical thinking.

At least that’s what physicist Carlo Rovelli argues in his book Anaximander and the Birth of Science. Before about 600 BCE, Greece was just another culture in the Near East, a backwater. After, it was a frothing stew of new ideas and new ways of thinking.5

What happened? Rovelli points out that the epicenter of this revolution is telling: it didn’t just happen “in Greece”, and it barely happened at all in Thebes or Argos or (God help us) Sparta. Rather, it started in Miletus, a city on the coast of Turkey. And what set Miletus apart? It was at the center of many trade routes; people who lived there had access to seeing many, many more cultures than most of the rest of Greece.

In other words, they could see that their own culture wasn’t necessarily the only game in town. They could question their own stories, doubt their methods of governance.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

I mean, that’s how!

But ironically this depends on some forms of information that are MYTHIC (🧙♂️) in nature: 🧙♂️PUZZLES and 🧙♂️CONTESTS and 🧙♂️PROVERBS and 🧙♂️STORIES. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

6. This might be especially useful for…

…kids who are interested in other cultures — perhaps because they’re bicultural themselves. And also weirdo kids who might, on their own, sit down in the library and teach themselves the Greek alphabet.6

7. Critical questions

Q: Who’d make these?

The obvious answer is “some teachers, who’d then sell them to others”, but the fuller answer is “anyone in the Egan-head community who’d like to make something wonderful”.

Q: But who even knows this many alphabets? Who could pull this off?

Almost any fool with an internet connection.7 A website like Lexilogos makes this easy.

Q: What should these messages actually SAY?

Cool quotes. Pithy proverbs. Little snippets of a story that swells throughout the whole year. Bad jokes.

Q: I think I’m confused as to how any student, lacking an understanding even of what different alphabets look like, might begin to decode these. Should teachers give hints?

Sounds like a useful idea! Of course, the goal is to walk a line between “feeding them a flowchart of what to do” and “abandoning them to fail”. I think it might be especially cool if there were books in the classroom that listed a bunch of alphabets, and kids could access those for help.

Q: What about kids who aren’t interested?

My hunch is that this is fine; that this is the sort of non-central curriculum that it’s better to let kids choose to not tackle than to force them to do it. (But I’m not sure this is more than personal taste.)

Can you think of another piercing question? Become a paid subscriber and join in the comments conversation. (Comments on the patterns stay open indefinitely, so we have the chance to evolve a rich dialogue.)

8. Classroom setup

Once again, we find that walls onto which things can be taped (and from which they can be de-taped without causing damage) are useful! Having a solid classroom printer (to produce these quickly) is probably also good.

9. Who else is doing this?

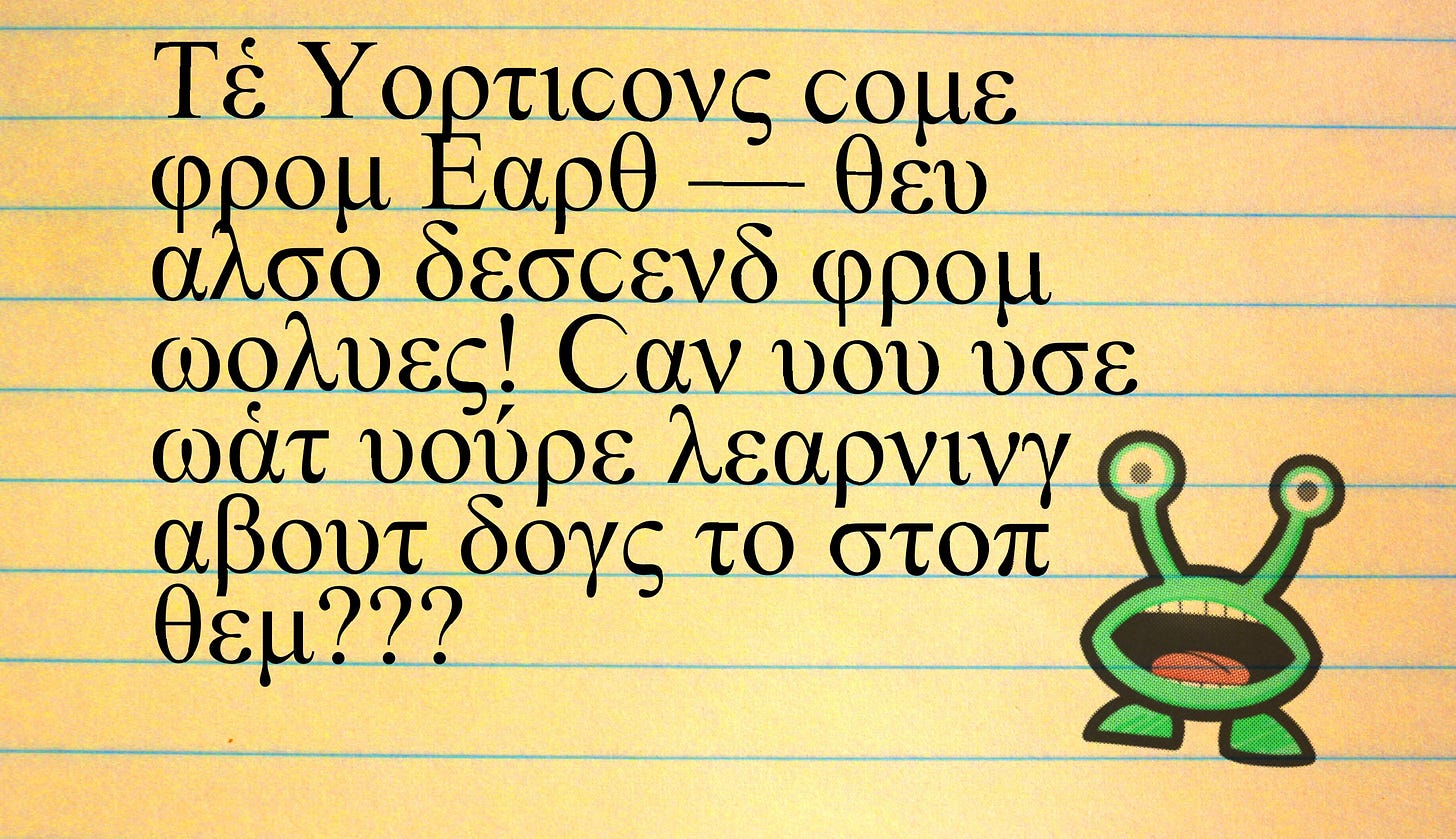

Nobody else that I know, but I experimented with this last year in my Science is WEIRD curriculum. Each week, kids got a coded message from an alien concerning plans for an invasion of Earth.

The story got somewhat convoluted — the Yorp who was at first only pretending to be your friend turned double-agent; he put you in touch with other members of the underground who were closer to the seat of power.8

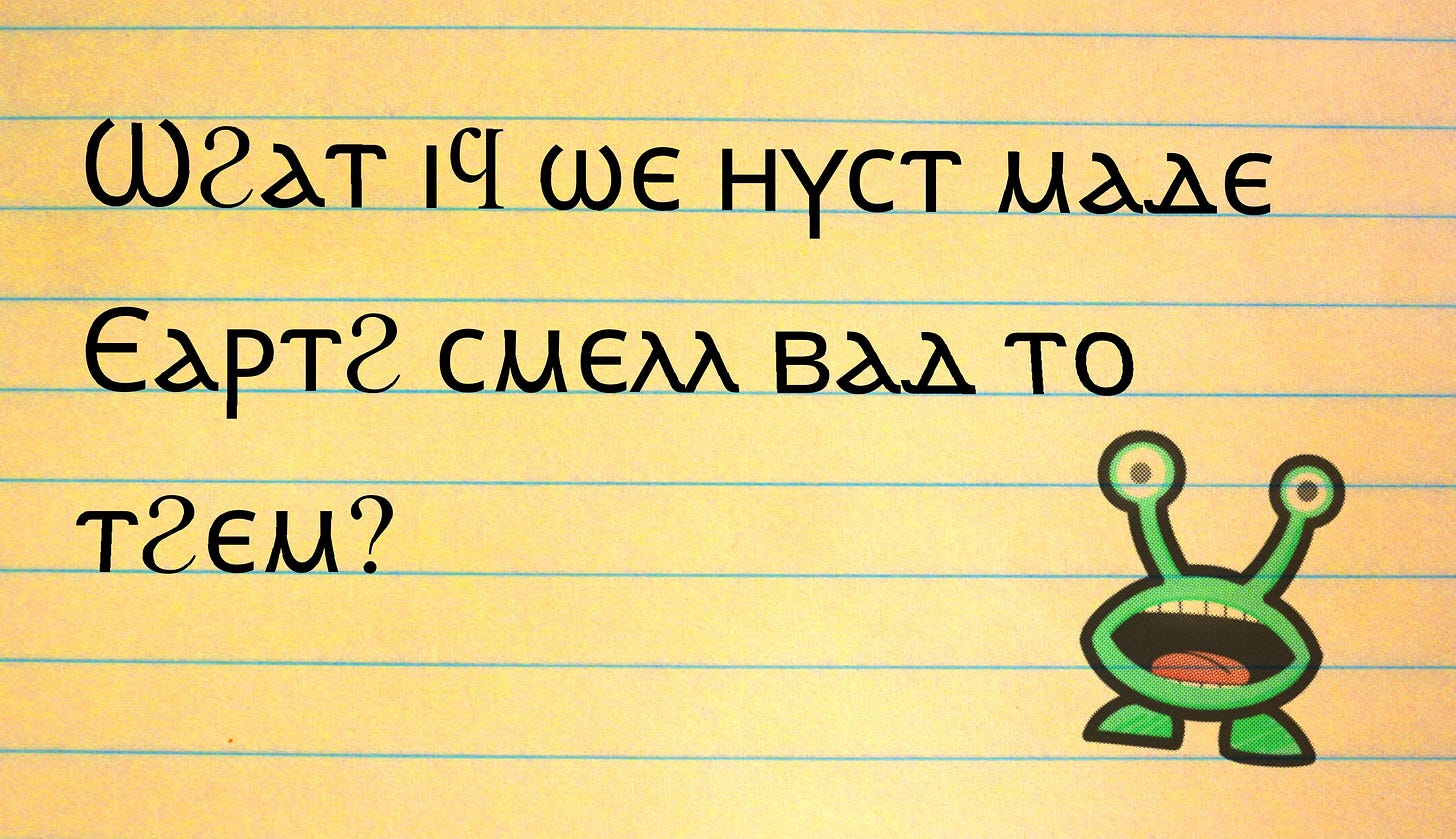

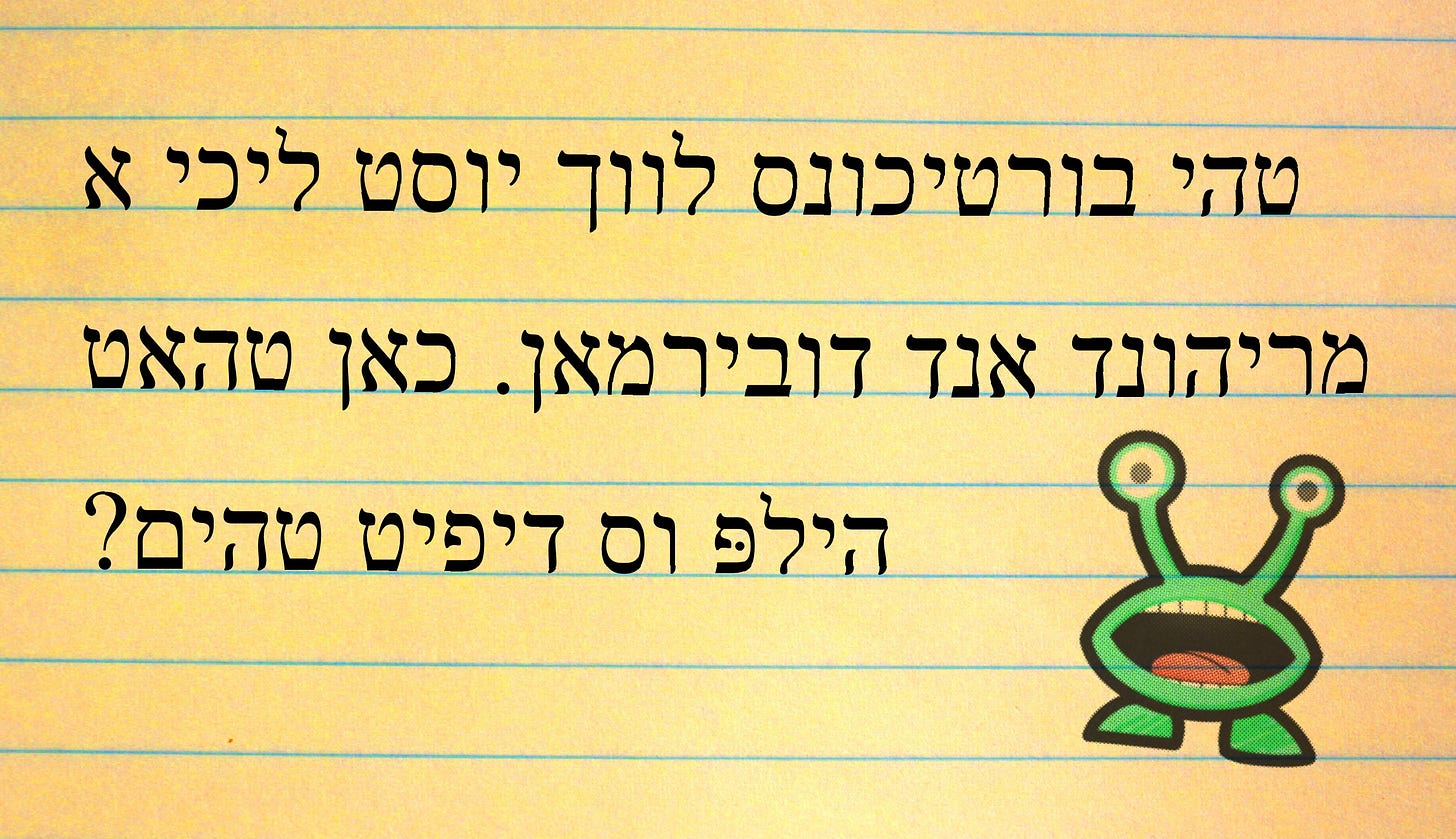

Anyway, not all of the messages used other alphabets — most were ciphered in more traditional ways. But here are some that my science kids saw —

Q: Brandon, this is NOT HOW ALPHABETS WORK.

I think you’re wrong, actually! We’re used to thinking that alphabets are organically connected to the languages they represent, but historically, that’s just often not true: and once again, English is a good example of this. Our alphabet should have letters like ð, θ, ʃ, tʃ, and ŋ; instead, we have pointless letters like “c” and “x”.

Q: This looks like a lot of work.

Eh, enough that I haven’t chosen to continue it this year — but honestly, probably just 20 minutes a week, and most of that was formatting the image, and thinking about where the story was headed.9 Once again, I recommend using a website like Lexilogos.

10. Related patterns

Really, this is just a riff on Ciphers° (which’ll post in September). After kids become acquainted with how other alphabets work (and perhaps spot the odd similarities between them) they’ll become eager to learn The Origin of the Alphabet° (it’ll post in March).

As noted above, the content of these messages could include World Proverbs° and Good Quotes°, and would be something great to spread in the Market for Lessons°.

Afterword: Going full-meta, here

I keep adding stuff to the site, then not announcing it! So note that the button above (“All the Patterns”) takes you to our new index of all the patterns that I have planned, along with the dates that you can expect a lot of them to drop. There are… many. (This is step 1 to “how can we scale Egan?” I’m pretty excited.)

Also, I’ve made a special page (link at the top of the homepage) that explains what the heck this “pattern language” thing really is.

ANNNND I did an interview with a Big Important Education Podcast recently! I’ll post about it shortly, but you can find it on the web here, and wherever else you get your podcasts. (Just look up “EdSurge”.)

The Romans looked indulged their “world domination” passion project a bit more passionately than others.

“But what about ð, θ, ʃ, tʃ, and ŋ?” I hear you International Phonetic Alphabet zealots freaks enthusiasts asking. Yes, this is exactly the tragedy: these letters actually exist, but they’re not part of the English alphabet.

An outdated name: there’s nothing “long” about them, but they replaced an earlier convention where some vowels were literally held for a longer time. Compare “You’re bad” as a put-down with “You’re baaaad” as a compliment. (I think I got this example from Steven Pinker’s The Language Instinct.)

Unless you’re one of the aforementioned IPA weirdos.

Egan’s term for this is “Philosophic understanding”.

Obviously, I don’t know anyone like this and I definitely didn’t spend my rainy recesses trying to learn Klingon. I mean, gosh, why would you even think that?

Which, alas, is almost every fool.

At the end of the year, students used their newfound understanding of the science of dogs to save the Earth. ‘Twas a good year.

Always. Plan. Ahead.

Haha, this one really repels me, but I never learned to read phonetically, so slowing down to think about sounds instead of words-as-meaning-units always throws me.

The part that makes sense to me is that when you look at unfamiliar language, you get to ask questions you grew right past when learning your native language. Learning French and Latin made me curious about English's grammar in a way that speaking English did not.

Semi-relatedly, you'll like this on English's different registers from germanic, french, and latinate roots: https://hellotailor.tumblr.com/post/741756025919651840

So (asks the singing geek) why not teach them IPA while you're at it?

Also, have you read Helen DeWitt's novel _The Last Samurai_? If not, I predict you will like it and find it to provoke thoughts useful for this post series.