A note: I’m always monkeying with this substack to figure out what works best; throughout March and April, we’ll be experimenting with keeping the comments section open to all subscribers (not just paid ones).

As we become the sort of community we pretend to be in the comment section, I’ll be zealously editing it for politeness towards other people, and staying leagues away from the culture war. That said: direct questioning of anything I wrote is much appreciated.

If you’re reading this in your email, click on the link, and see you in the comments!

1. A problem

“Ah, music,” he said, wiping his eyes. “A magic beyond all we do here!”

– Dumbledore in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

Music (even when it lacks words, and sometimes especially when it lacks words) does things to us that we struggle to make sense of with words. Good music is strangely profound.

But schools don’t spend much time on it, and when they do, they tend to focus on precisely the parts that we can explain with words — styles, artists, dates, and key signatures.

2. Basic plan

Put kids in contact with powerful music in which lyrics play a small role (or are absent entirely).

Choose music that’s as diverse as possible to expand their aesthetic imaginations.

Give them repeatable methods to translate their experience to another medium.

Finally, help them see how the music flows out of (and back into) the whole human story.

3. What you might see

Students avidly listening to symphonies & solo piano, film scores & modal jazz, electronic ambient & minimalist, Gregorian chant & flamenco, Indian classical & Sufi devotional, Celtic folk & African drumming, Indonesian Gamelan & Japanese Koto. Students listening to recordings of birdsong, whale song, wolves howling, and frog choruses. (Yeah, I left some out.)

And then, students “drawing sound”. Here’s how:

choose the medium they’ll draw in (e.g. crayon, colored pencil, watercolor) before they hear the music

let them choose a color

play the piece of music once

choose a shape (e.g. rectangles, scalene triangles, diagonal lines) they’ll limit themselves to drawing

play the music a second time

let them try to convey their experience of it in a drawing

The big rule: the drawing can’t be representative or symbolic. That is, it can’t point to something outside the song (e.g. a picture of a didgeridoo, or of their grandfather who played the didgeridoo). That also means no words or numbers.

Afterwards, you might see students comparing their drawings with each other, and saying, “whoa, you didn’t perceive this at all like I did.”

You might also see kids doing the “musicality challenges” we mentioned in our Song a Week° pattern:

Students listening intently, laser-focusing their attention on a single aspect: can they tap out the drum’s rhythm? Can they hum the flourish of the piccolo trumpet? Heck, how many of the instruments can they name? Can the musically-inclined re-create the basic melody on a synthesizer? Can they sing it?

4. Why?

People chase musical experience hard. It’s almost like it’s a drug, and everybody needs their fix.

And they pay for it: Americans alone spend billions of dollars just on live music each year.

Yet most educational philosophies treat this as an afterthought at best because it’s not “rational” or “practical”. It doesn’t fit in our categories for how learning works.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Where to start? Shamanic drumming in Siberia, Sufi dancing across the Islamic world, raga performance with sitars in the Indian classical tradition. Drum circles in West Africa, Berber music in Tunisia. Getting really really into mostly-instrumental music with the people around you seems to be part and parcel of human societies across the world, and across time.

What’s weird1 is where we don’t see it as much: the modern West, which is to say, where you are presently reading this on your phone. (“But what about raves?” you ask? See the Q/A below.) And heck, let’s brainstorm a few reasons why —

we’re an individualistic society: we keep our profound experiences private

we’re a publicly secular society: communal music has always been, throughout history, religious

we’re a predominantly Protestant society: Protestantism has historically stamped down on public outbursts of emotion2

Add to that the fact that the European culture that’s gone global has, for centuries, lauded reason over emotion, and you get a perfect storm against communal experiences of mysterious music.

This seems impossible to live in… which explains why, for the last century, people have been refusing to live in it! Jazz clubs, psychedelic rock concerts, rave culture, house music — these are all signs of the crabs crawling out of the bucket. Welcome to modernity: we don’t like it here.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

The roots of this pattern are SOMATIC: it’s 🤸♀️MUSICALITY, pure and simple. Crank it up loud enough, it’s 🤸♀️BODILY SENSATIONS. Through whatever deep magic Dumbledore was speaking of, it connects straight to 🤸♀️EMOTIONS. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

But wait, there’s more! By learning about the 🧙♂️STORIES of the people and cultures that produced the music, we get 🦹♂️HUMANIZING KNOWLEDGE. (And that, in turn, can become humanizing knowledge to other subjects — see “Related Patterns” below.)

Unexpectedly, this pattern is a seedbed of a lot of very difficult-to-access PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) understanding. I speak, of course, of music theory, which is (as it says in the tin) a type of 👩🔬THEORY.

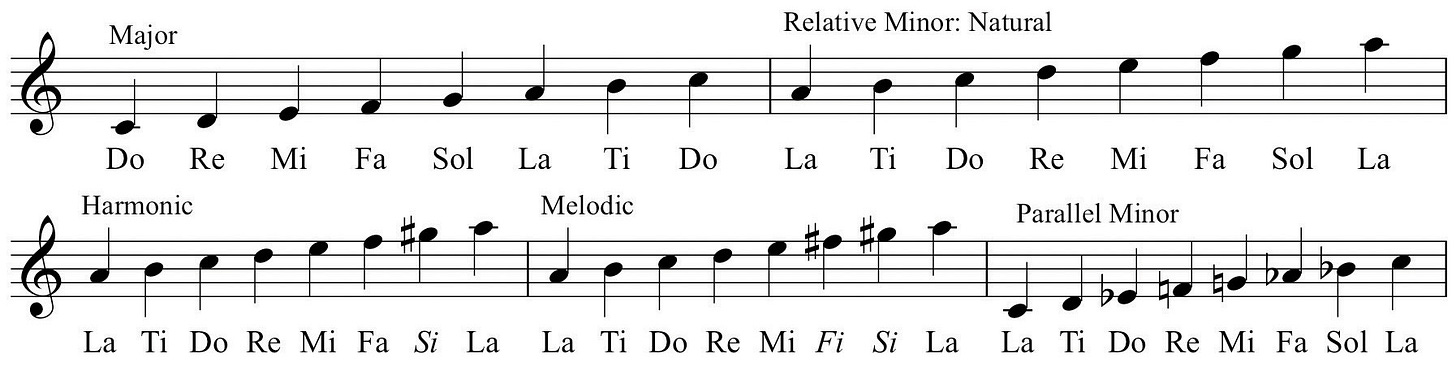

I think it was in third grade when my class learned the rudiments of music theory (things like quarter notes, eighth notes, and time signatures) in our twice-a-week music class. I remember that at the time it felt dry. Abstract. Pointless! The examples we were shown felt worlds away from any actual music that anyone would perform.

How much better it would have been, I think now, if instead of starting with something like quarter notes, we immersed ourselves in mysterious music, experimented with tapping it out, and learned about quarter notes as simple tools to make sense of what we were hearing. (This, of course, is how quarter notes themselves evolved. They’re not a natural fact of the Universe — they were an attempt to make sense of how medieval chant worked.)

I get excited when I think how much further into Philosophic understanding this could go. We could introduce students to minor keys to help them understand why some music feels “dark”, and talk about pitch vs. note vs. harmony to understand what’s really going on in a sound.

This even opens up some of the bigger questions of the humanities and sciences — is a minor chord’s “darkness” something genetically coded into us, or is it cultural? Is there anything “natural” about the octatonic scale (the eight notes of “do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do”), or is it arbitrary? Do dogs and cats and chimpanzees like our music? Why does music even exist — did it help our ancestors survive, or is it (in Steven Pinker’s immortal phrase) “auditory cheesecake”?

That is, we can hope to delve into deep music theory.

6. This might be especially useful for…

That stoner kid who paid no attention in class but spent all his afterschool hours mastering “Stairway to Heaven” on his Gibson guitar.

7. Critical questions

Q: You said that our culture has abandoned communal music, but you also admit that we have it in the form of raves and so on. You, sir, contradict yourself!

Contemporary communal music experiences are the exceptions that prove the (broader) rule in that we have to step outside of mainstream society to participate in them. These experiences are practiced by subcultures and done in private venues. In our ancestral past, they were practiced by everyone and done in public. They used to knit together society — now they knit together small groups of like-minded people.

Q: Aren’t you getting a bit optimistic about how deep into music theory you can go with kids?

Well, I’m not suggesting that we’d get there quickly. The harder stuff — conversations about octatonic scales and whatnot — would come more naturally to teens who’ve explored mysterious music for years (and would have themselves tried their hand at by playing a few instruments).

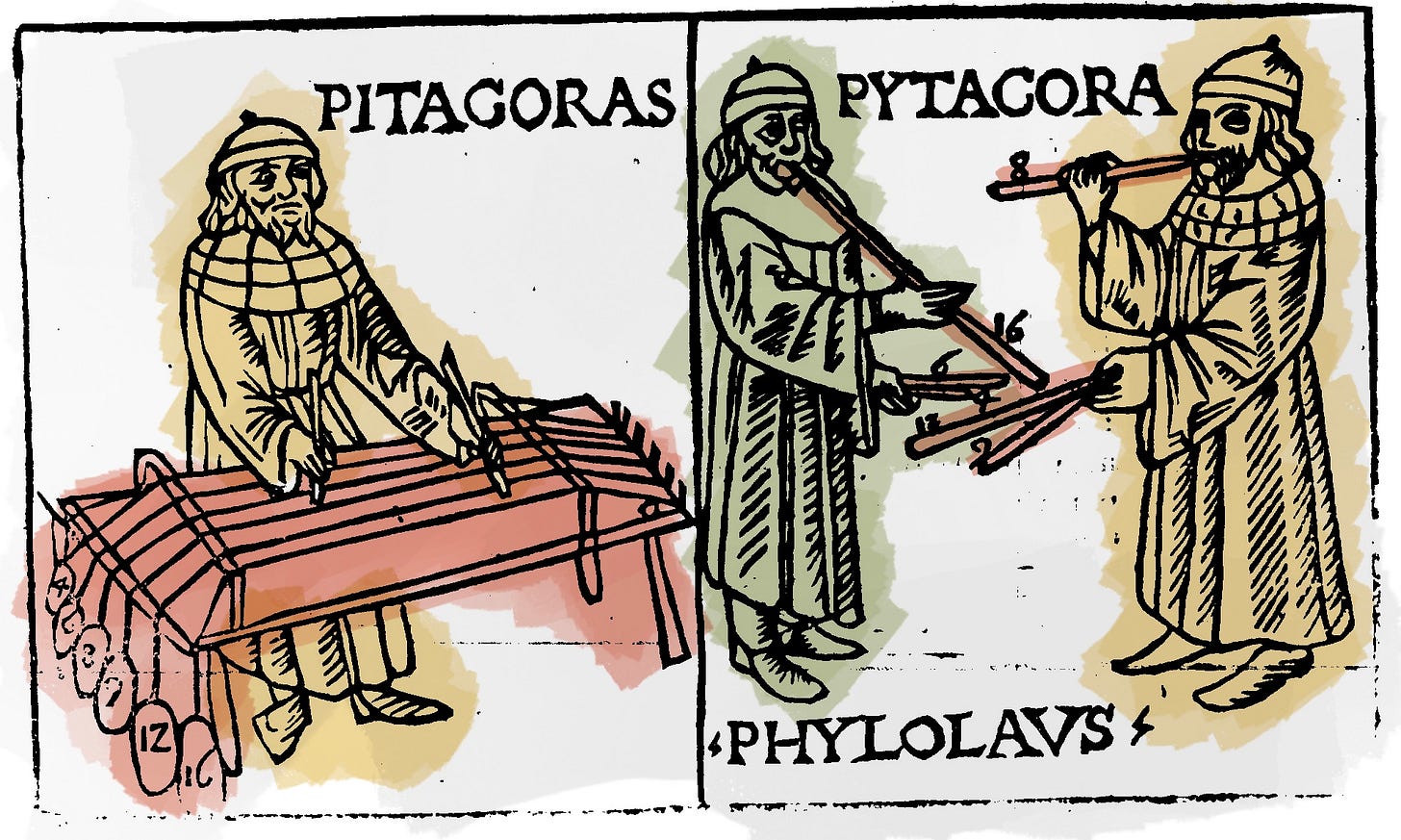

But look, in ancient Greece a lot of math (ratios, especially) was developed specifically to make sense of how music worked. The power of music has been harnessed to analytical ends before; we can hope to do it again.

Q: In Drawing Sound, why can’t kids choose their color?

For the same reasons of symbolism — you don’t want them choosing blue to symbolize “sadness”, or red to symbolize “romance”.

Q: Why should the adult making all the choices in that game?

In part because it frees up kids to do the thing. The essence of these choices is that they’re random — they get in the way of listening to the music. Also in part because it makes it natural to compare everyone’s drawings… which is half of the fun of the pattern!

Oi, these things are fun to write — but ACK do they take time! When you become a paid subscriber, you make it easier for me to thrust aside my parenting career various not-technically-essential responsibilities and write MORE.

8. Physical space

At home

Most homes already have better speakers than are strictly speaking necessary for this pattern, so no need to worry there.3

For Drawing Sound, if you want to randomize the color & shape from a list, that could take away even the possibility that you’re sneaking some symbolic meaning into it. Some dice (and perhaps even excessively-sided nerd dice4) might do nicely. Given the age of the kid, you could make this a math challenge of sorts: how might we properly randomize these options?

In a classroom

“The classroom next door is making too much damn noise” is a potential problem, one to work out between teachers. If one has lots of money to throw at a building a new school, though, it might be wise to invest in sound dampening and sound proofing, if only in one special room that classes can take turns in (with a real killer speaker setup).

9. Who else is doing this?

An occupational therapist friend tells me about helping her neurodiverse clients experience music as a way to help them talk about feelings.

Most obviously, getting kids inside the music is something that happens in every middle-school band and orchestra. There, though, the focus is on performance — here, the focus is on the experience.

Oh! Something something music therapy. (If you’re reading this, and have any experience in this field, join in the comments!)

How might we start small, now?

I feel like the coolest part of this pattern is something I haven’t spoken directly about: that moment when you realize that the people around you are having wildly different aesthetic experiences than you! Sociality is at the core of this pattern.

So how about we try this here? Grab a piece of paper and a black pen or pencil, turn your amp up to “11”, and click here to listen to this piece of music (no, I won’t tell you what it is beforehand).5 As you listen to it, try to convey your experience through drawing rectangles. (If you want to listen to it once first, go ahead.)

Then snap a photo of what you’ve put onto the paper, and send it to vicki@eganeducation.com with the subject “Drawing Sound”. We’ll put up a post with them in a week. (Feel free to include your name / Substack handle — just put it in the email.)

And below, write in a comment about how your experience went.

10. Related patterns

This is basically A Song a Week° without words (or at least not focusing on the words). It gets more power from Making Noise° and Playing Instruments° (August 14).

Like Strange Sensations°, it’s an attempt to focus on the purely somatic, and like Aesthetics, Unpacked° it’s a good way to move from “I’m feeling something!” to “I have a theory as to what’s going on here”.

And it’s one piece of how we can hope to make it normal to share intimate aesthetic experiences… a norm that will help us lose ourselves in Dancing in the Classroom° (September 6).

Finally, we can use this to secure an emotional anchor to different cultures we study; this’ll automatically make Spiral History° and Geography by Heart° much more interesting.

Afterword:

Hey, see what I did up there in section 8, when I turned “Classroom Setup” into “Physical Space”, and split it into “At Home” and “In a Classroom”? I’ve come to realize that the next step in setting Egan loose on the world is to help parents (and especially homeschooling parents) do this themselves, and want to be more obvious about that. (This is just the start of a bigger project… stay tuned.)

Once again, if you’re reading this, you can comment — for the next month and change, you don’t have to be a paying subscriber!

“WEIRD”, but we’ll make that joke with Dancing in the Classroom° later.

For this story, see Barbara Ehrenreich’s Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, which we’ll be drawing from a lot in Dancing in the Classroom°.

I say this as someone who doesn’t, and am bowled over every time I visit someone else’s home.

Yes, I know my audience.

I guess there are captions with the translated lyrics? I recommend keeping those “off”, at least at this stage.

I really like this, because I often feel like music isn't something I can get _purchase_ on and therefore can't discuss and therefore make a smaller part of my life. There were some visualizations of classical music on youtube I really liked because suddenly I could *see* repeating patterns and the intersection of different voices in the piece versus just hearing MUSIC.

Reading one of my other substacks this morning, the author spoke about how helpful the comments were to his writing. As you have opened the comments, I wanted to take a moment to tell you how helpful and informative I find your posts and how much I regret not knowing about Egan and your interpretations during the time I was homeschooling my boys. Thanks you for taking the time to share your knowledge and interpretations. I know you will make a difference in the world of education!