1. A problem

Every story tells a lie — that is, every narrative privileges one perspective and one set of values. This is true by necessity: there’s no way to avoid it.

Any approach to history that uses 🧙♂️STORIES (like ours) must face up to this, and get clever.

2. Basic plan

Tell some of the major stories of history from opposing perspectives. Early on in the curriculum, do this occasionally, from the perspectives of different characters. In middle school do this more often, from the perspectives of different sides. In high school, do this more often still, from the perspectives of different ideologies.

3. What you might see

Kids. Engaged. In. History.

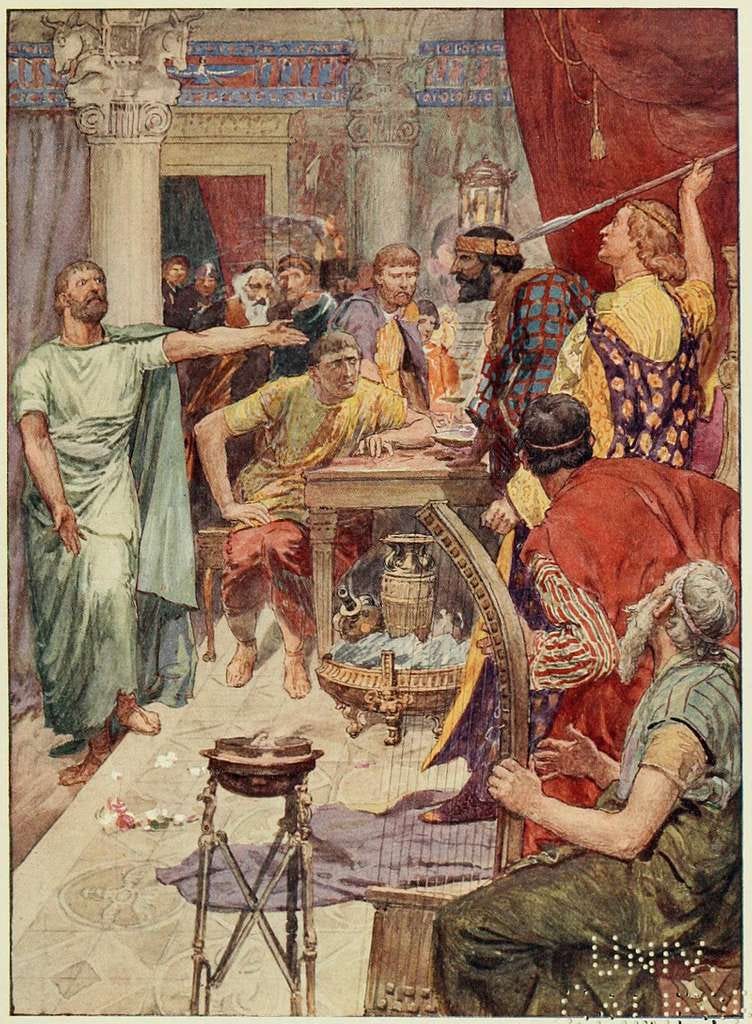

First graders hearing, as part of the saga of Alexander the Great, the perspective of his trusted companion Clitus, who had previously saved Alexander’s life, but who was increasingly uncomfortable with his friend’s adoption of Persian customs and his downplaying of the role his men played in their victories… which all culminated in a drunken accusal at a fateful dinner in Samarkand.

Fifth graders hearing the story of the Greco-Persian War from the heroic perspective of the diverse Greeks who banded together to defend their local ways of life against imperial expansion… and then hearing the same story from the perspective of the Persians, willing to sacrifice themselves to hold together the hard-won Persian Peace.

Twelfth graders examining the Cold War from the perspectives of a Trotskyite, a Randian Objectivist, a pacifist, and a post-colonialist.

4. Why?

The simple way to fix this problem has failed utterly.

That 🧙♂️STORIES bring bias isn’t news. The usual way to fix it is to, well, avoid stories — to retreat from narratives into objective facts, and to tell about the past from the perspective of “nowhere”.

As James Loewen gorgeously exposed in his book Lies My Teacher Told Me, this

makes history insufferably boring, and

fails spectacularly at its own goals.

Instead of avoiding bias, this approach hides it, and allows it to metastasize.

There is no way out of the biases that come along with stories — the only good option is to work hard to find clever ways through.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

People have been doing this for a long time: Herodotus (“the Father of History”), for example, gives us two separate stories of what caused the Trojan War.1

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

Everyone loves a 🧙♂️FIGHT, and 👩🔬BATTLING IDEAS are at the heart of PHILOSOPHIC understanding. Try to get to the bottom of these conflicts (which side is really correct?) often leads us to an IRONIC appreciation of 😏AMBIGUITIES. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

6. This might be especially useful for…

Ornery people who object to the bias they (correctly) smell in official accounts.

7. Critical questions

Q: Won’t this confuse students?

Absolutely, which is a sign we’re moving in the right direction. (If you’re not confused, you’re not paying attention!)

Q: Isn’t confusion… bad?

There’s a balance to be struck between clear understanding and confusion. Education fails when it veers too close to either extreme.

Q: How do you choose which perspectives to present?

Carefully. Thoughtfully. (I trust that no thinks I’m in any position to declare what the One True Set of Perspectives is.)

Q: But can’t you give us any tips?

For elementary school:

Don’t rush to ideologies — practice, first, with people.

Use this sparingly — it’s hard to do this well; perhaps three or four stories per year suffices.

For middle school:

Be bold in representing your own values / the values of the school.

Be bold in representing the perspectives of groups that you have a hard time empathizing with.

For high school:

If the parents of the kids in class aren’t getting nervous, you’re probably not going far enough.

Q: Isn’t the act of choosing perspectives itself… an exercise in bias?

Yes! Like I said before — this doesn’t get us out of the problem; it’s just the best way to muddle through.

Q: This seems too hard to do well.

It’s impossible to do perfectly: the number of perspectives in a historical story is uncountable. However, there’s a safety net built into this: if you do this enough, students will begin to look for the bias in stories.

You got insights into this? We could probably use ‘em! Become a subscriber and join in the comments conversation.

8. Physical space

(Nah. This is purely a mental thing.)

9. Who else is doing this?

When I graduated college with a degree in history, someone2 gifted me a year’s subscription to The Journal of American History. Most of the articles were interesting, but my very first issue had an article that changed my life.

It was by Lendol Calder, professor of history at Augustana College, titled “Uncoverage: Towards a Signature Pedagogy of the History Curriculum”.

In it, Calder laid out how he taught American history to undergraduates. I suspect Kieran Egan would have loved his method. It three steps — take a peek at the website he’s made to learn more — but at its center is the act of reading two opposing popular historians against each other.

On the Right is Paul Johnson, a British intellectual who became an ardent supporter of Margaret Thatcher’s government. On the Left is Howard Zinn, a radical American intellectual who (1) told the story of America from the perspective of marginalized groups, and (2) inspired one of more memorable lines in Good Will Hunting:

This brings the 🧙♂️FIGHT to the forefront of our attention.

It’s been a while since I’ve taught history, but I used to have high school students read chapters of Zinn’s People’s History of the United States against Johnson’s History of the American People, and then discuss the differences. (For middle schoolers, we used the young reader’s edition of Zinn, and vacillated between a couple different choices for the conservative one.)

There’s more to this — like the introductory cycle of watching a movie for each era, and the third cycle of… well, if you’re interested, Calder’s original article can now be read online. (Highly recommended, and well-written to boot.)

How might we start small, now?

Include in your home library a book on a topic you love whose perspective you hate, and call your kid’s attention to them.

10. Related patterns

It’s easy to go nuts with this pattern — but disagreement isn’t the sole ingredient in history! Sprinkle these into Epic Stories° told in a Spiral History° model; in the early years, you can treat this as just another part of Playing Inside Stories°.

To give students power over narratives, teach them how a narrative works by helping them master Story Ingredients°.

The choice of which perspectives to include is something that should be informed by some of the culture-war-adjacent patterns I’ve been putting off writing, because I’m a coward — Named Virtues°, Every School a Tribe°, and Radical Inclusivity° — and one that’s scheduled for the fall — Within/Above/Beyond the Culture Wars°.

Afterword:

Wow, it’s been a while since I posted! The culprit is a mesh of big, time-sensitive projects — a podcast interview (which’ll be coming out soon), two epic posts (ditto), the Learning in Depth cohort (which’ll start Monday, and there are a few seats left), and the book I’m writing explaining how Egan can infuse parenting.

Frankly, these have been amazing to get to work on. You’ll be hearing more about them here, and soon. In the meantime, I’m switching my posting schedule to one new pattern per week, which is a pace that I think I can keep up with.

The first is the one we’ve all heard, about the beautiful Helen being abducted and so on. The second… reads like a crazy conspiracy theory? According to Herodotus, the Egyptians said that the ship Helen was on accidentally crashed in their land; she stayed there, unbothered, for the duration of the war.

I’m embarrassed to say I either never found out, or forgot. If it was you, let me know!

I appreciate the utility of dueling narratives; being able to assess two (or more) sides to an argument is fundamental skill. Educational institutions should strive to equip people so that they can do this well.

That said, I'm cautious about Zinn vs. Johnson. Zinn is a polemicist, and I consider his book for kids to be actively damaging. I don't know anything about Paul Johnson, but he's a polemicist as well I don't know that anyone would learn much by playing one off against the other. You would do much better to find two truth-seekers who have come to opposite conclusions about some significant issue. A contemporary example worthy of study in this way might be the 1619 Project; there are multiple views pro- and con-, but I don't think that anyone is guilty of acting in bad father.

I think humans are thrilled by the conflict of contrasting viewpoints. Our brains must light up whenever there are sides to take. It draws us in and activates us. It's not just that kids need to learn how to figure out the truth out of opposing viewpoint. Yes, that's great. It's also that this, if done right, can draw them in. And now we can also simulate the contrasting viewpoints with AI and make it a conversation, eventually getting the students to join in. I can't wait to see it in practice.