Towers and kids' brains and bears, oh my!

Cognitive psychology, meet Kieran Egan. And... fight!

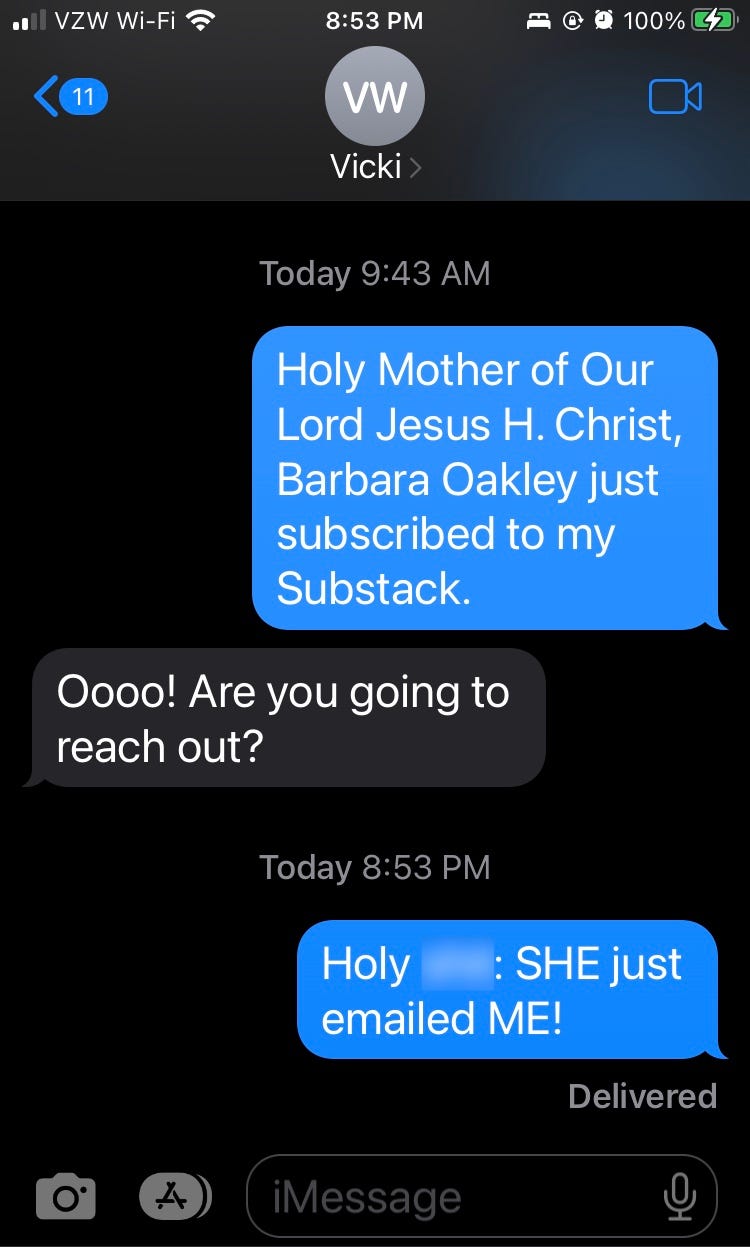

From a conversation with my friend Vicki, about a week after my book review won the ACX contest:

I’m guessing that you know who Barbara Oakley is because (1) she’s a rock star of education,1 and (2) she just gave us a major shout-out on her newsletter, which reaches something like three orders of magnitude more people than our homely substack!

What you probably don’t know is that Barb changed my life nine years ago.

I was thirty-two, and struggling to figure out how to focus the effect I wanted to have in the world. I saw two roads.

The first road was cognitive psychology. I had spent a decade in high-end test-prep coaching where I mainlined books on cognitive psychology (expertise, memory, creativity…) to devise new ways to help students weaponize their minds. I had created some pretty powerful tools (of which the Deep Practice Book was just one)… and I was ticked off when I’d walk into bookstores. Why?

In the psychology section, there’d be exciting books by real cognitive scientists unveiling bold new possibilities for learning.2 But in the education section, there’d be lame books by hucksters on “study tips” — re-heatings of the same tasteless, nutrition-less leftovers I had had as a kid.

This gap needed to be bridged. And someone needed to bridge it! These ideas needed to be let out into the world, goshdarnit! And I suspected that I could do that.

That’s the first road. The second road was Egan’s — to popularize what I was learning by devouring Kieran Egan’s work, meeting with his team, experimenting in my humanities classrooms (I used to run oddball seminars in the Seattle homeschooling community),3 and presenting at their conferences.

These ideas, too, needed to be let out! There were essays to be written, TED talks to be delivered. And I suspected I could do that, too… but not both.

So which would it be? How could I bring more goodness to the world? Cognitive science or Kieran Egan? Hallows or Horcruxes?

Then I found Barb’s 2014 book A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even if You Flunked Algebra), and I thought: thank God, someone’s said it better than I could, now I can do the other thing. Barb’s work (then and since) gathers all the great stuff that’s been coming out cognitive psychology in the last thirty years and positively weaponizes it for students and teachers.

No Mind for Numbers, no review of Egan.

Egan and Oakley

Imaginary Interlocutor: Brandon, it sounds like there’s no real connection between Egan’s approach and the stuff Barb does.

No, the exact opposite: which is why this newsletter exists!

Imaginary Interlocutor: Explain how!

How can I state this simply?

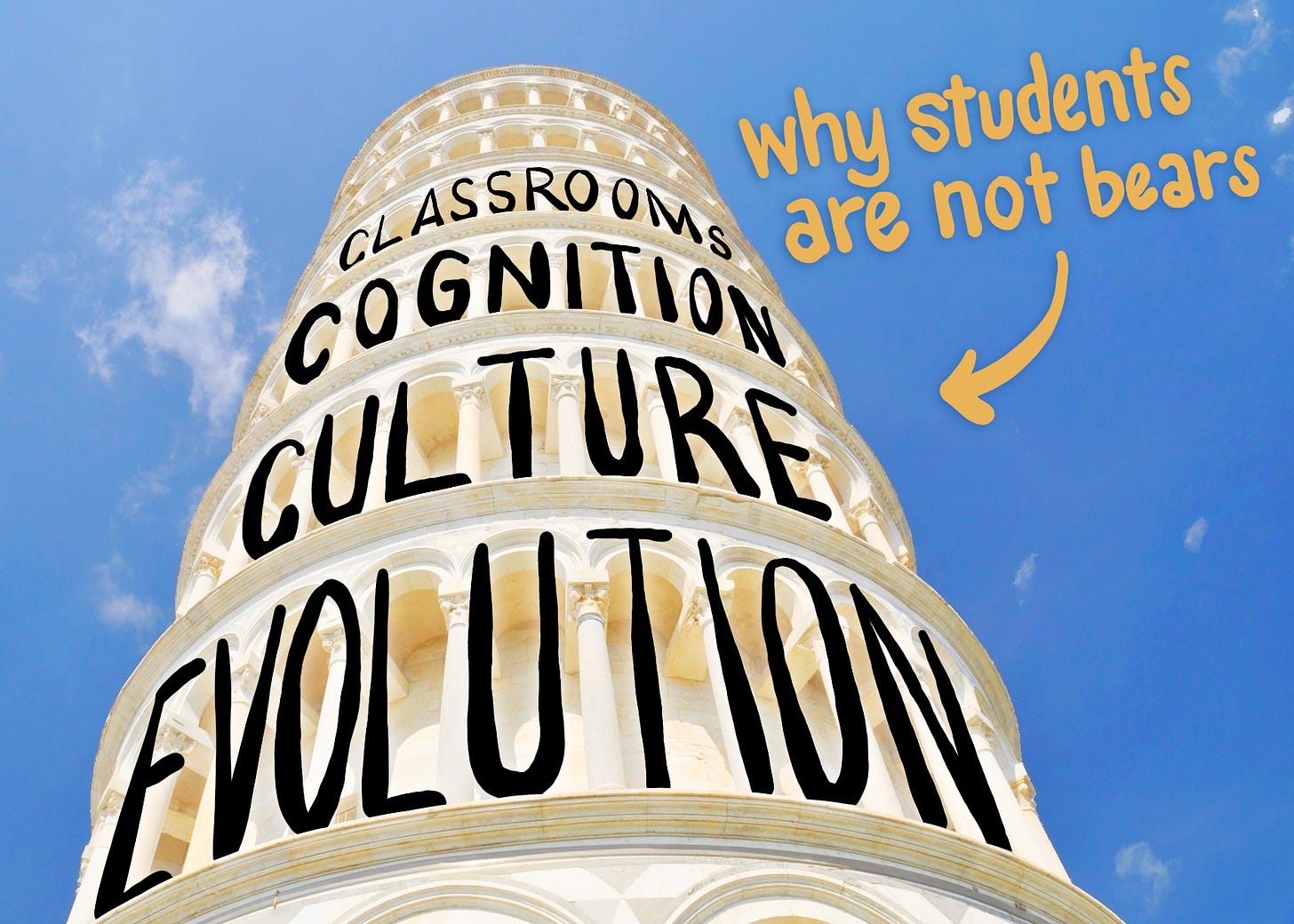

Education is confusing, because humans are an unusually convoluted, multilayered creature. The better we understand each layer, the better education can become.

That’s too abstract. Let me try to add in another level of complexity, my favorite quote from David Brooks’s The Social Animal:

The truth is, starting even from birth, we inherit a great river of knowledge, a great flow of patterns coming from many ages and sources. The information that comes from deep in the evolutionary past, we call genetics. The information revealed thousands of years ago, we call religion. The information passed along from hundreds of years ago, we call culture. The information passed along from decades ago, we call family, and the information offered years, months, days or hours ago, we call education and advice. But it is all information, and it all flows from the dead through us and to the unborn. The brain is adapted to the river of knowledge and its many currents and tributaries, and it exists as a creature of that river the way a trout exists in a stream. Our thoughts are profoundly molded by this long historic flow, and none of us exists, self-made, in isolation from it. So even a newborn possesses this rich legacy, and is built to absorb more, and to contribute back to this long current.

(Dunking on David Brooks is a hallowed Twitter pastime, I’m led to understand, and I know I don’t agree with everything he’s written. But whenever I meet one of his haters, I want to ask, who else do you read who can state the big picture of learning so elegantly?)4

I.I.: Yes, very vibe-y. But why do you bring that up?

It feels like everyone who has something important to say about education is fixated on some particular level.

There are the cognitivists (Barb is one). They’re focused on what’s happening in an individual’s mind: how does our memory work, and our attention, and our reasoning?

There are the social and cultural people. They’re focused on a more fundamental level: how do our cultures and societies shape how we see the world, and what we value?

There are the evolutionary folk. They’re focused on an even lower level: what does our specific evolutionary heritage suggest about how schooling (Traditionalist, Progressivist, industrial, whatever) might be running afoul of human nature?

Meanwhile, at the top, most professional teachers pay little attention to any of this, and just focus on the unique, idiosyncratic students that they get to work with in their classrooms.

I.I.: Which of those levels is right?

They’re all right!

I.I.: Okay, but which of those is the best?

They’re all the best! A human being is all of them together! We’re an uniquely multilayers, convoluted animal!

Maybe I can explain this better by comparing us to bears.5

Bears are a fun stand-in for a fellow mammal that’s omnivorous, unhoofed, not particularly dim, and sometimes stands on two legs.

We can talk about a bear’s cognition. (How long can it remember where the choicest raspberry bush was? How quickly can it figure out how to open a bear-proof trashcan?) We can talk about a bear’s evolved nature. We can even talk about whether bears have culture: are there habits that mother bears learned from their mothers, which they pass along to their cubs? And bear-trainers can swap tricks for dealing with this or that particular bear.

So far, a kid might seem like an above-average bear.

Well: humans aren’t bears.6 There’s a difference between humans and every other mammal — every other organism — and it’s remade us into a fundamentally new kind of creature.

In the last few million years, natural selection has taken us down what seems to be a novel path. Our cavemen ancestors were able to store and communicate meaningful information to a degree no other organism ever could; this made us able to work together in teams that acted like their own organisms.

Then the forces of Darwinian selection worked on those teams; cultures competed, mutated, and were pruned. Our brains evolved to better take advantage of the cultures that made it.7

The secret of our success, as the Harvard polymath Joseph Henrich puts it, isn’t that we’re so very clever individually. It’s our ability to tap into the the cleverness that those who came before us came up with — and to riff on that.

We’re still a type of mammal, of course. But we’ve also become a new kind of organism. You can’t understand what we do without understanding all four levels: evolution, culture, cognition, and the quirks of each individual kid in a classroom.

Our ancestors played with memes, and the memes played back.

Why do so many of our educational theories crash and burn the moment they enter the classroom? Because they’re not based on the big history perspective of what we are.

Egan’s framework is.8

I.I.: So what? What does this have to do with Barbara Oakley’s work?

Egan’s framework isn’t enough. Bringing his vision into being doesn’t mean rejecting other approaches. Our task is to draw from many different educational perspectives, each of which understands something important about what humans are like, and integrate them together.

Egan provides a framework strong enough to bear that load. And Barb’s insights help us fill in one layer of the structure.

I.I.: I’m still confused on the connection here. Please finish this sentence: “The link between Barbara Oakley’s work and Kieran Egan’s work is…”

Okay, this is harder than I thought. Let me take a few cracks at this.

Maybe: Barb uncovers how learning works in individual brains; Kieran uncovers how this learning is part of a millennia-long saga?

Or maybe: Barb explains cognitive things like attention, memory, and thinking; Kieran explain affective things like meaning, motivation, and excitement?

How about this: Barb is writing to motivated learners; Kieran is writing to people who want to help virtually everyone become a motivated learner?

What we need to do is connect these levels. And right now, no other approach to education that I know about shows us how to do that.

Okay, I’m struggling here! I invite comments from those of us who’ve read (and loved) the work of both. What I do know is that there’s a deep connection between these approaches. Barb said it best, when she and I were meeting. She was describing reading my book review of Egan’s The Educated Mind:

I keep reading this, and I’m like, ‘whoop, I know the neuroscience that backs that up, and I know the neuroscience that backs that up’…

Which is to say: THERE IS A PROFOUND CONNECTION HERE AND I KNOW I’M NOT NAILING IT. Those of us who know something about the cognitive approach and Egan’s approach — help us out a little! How do you see this connection? What am I missing?

Greeting, noobs!

We’ve gotten lots of new sign-ups from Barb’s sharing of our little spot on the internet. (THANK YOU, BARB!) So, if you’re new to this substack, what can you expect?

Our quest is to unpack Egan’s vision of education, so people (teachers, parents, parent-teachers, homeschoolers, school-schoolers, students, self-motivated learners, very intelligent seals, super-intelligent shades of the color blue…) can experiment with his method.

The writing on here is… eclectic! Expect posts to veer erratically between the high-level and the super-practical.

Right now I’m working on a few posts:

Egan in a nutshell: how to understand Egan’s world-changing idea without reading a 22,000-word book review9

Lots of simple examples of what Eganizing education can look like

Why billionaires’ investments into “personalized learning” keeps flopping (hint: they’re forgetting what a person is)

How Egan can transform the 1st–12th grade social studies curriculum

Beyond that, last week we ran a contest to see who could de-risk Egan education the best. I’m collating those entries, and will be dubbing one person a winner soon.

Expect posts channeling Egan on how the glories of subjects like reading, vocabulary, spelling, philosophy, cooking, jujitsu, and so on can be made obvious to every student. Expect, too, some direct comparisons between Egan’s vision for school compared to Montessori schools, classical education, and Progressivist schools.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Egan and AI: both how we teachers can use AI to make Egan’s methods easier,10 and how Egan’s insights into how the operating systems of human minds really work can influence the design of large-language model AI’s like ChatGPT.

And expect an unveiling of something big and exciting to do with one of Egan’s simplest, greatest ideas: Learning in Depth. (I’m sworn to secrecy about it right now. Just sayin’.)

And, hey, maybe we’ll get some guest posts on how people can start Egan-fueled microschools! (Because I most certainly want to learn the nuts and bolts of that so I can pass them along.)

Anyhoo, it’s my joy to get to finally introduce these groups — cog-sci-lovers, and Eganheads — to each other.

Oh hey I’m selling out

There’s so much to write about, and I’m finding it hard to dedicate the necessary time to writing! (Y’know, I run a business.) In a couple weeks, I’ll be turning on paid subscriptions. I need to work out the details, but right now I’m thinking that paid subscribers will be able to…

attend some live events, like book clubs and “let’s Eganize this lesson” meetings

propose questions for me to directly answer

comment on some particularly spicy posts

feel that warm glow of providing a direct incentive to a writer in need11

And maybe I’ll be able to pay someone a little to moderate the comments! But, y’know, I’m figuring this out as I go along. So we’ll see. Feel free to suggest more perks in the comments.

“Winner of the McGraw Prize in Education”, “Queen of MOOCs”, and “Mother of Dragons” are just some of her many titles.

Most of which, as I look back, survived the replication crisis well. Nice luck, past me!

Have you taught courses on human flourishing, futurology, philosophical worldviews, the many varieties of feminism, the making of crêpes, and the psychology of evil? I have.

Which is a long way to say: I recommend that book, both for adults and kids (my 11-year-old daughter is re-reading it right now).

Or maybe not; let’s find out.

[citation needed]

As Jonathan Haidt puts it: we’re 90% ape, and 10% bee.

This is why, in the book review, I said he’s “Joe Henrich for education”.

Though you can also listen to Jeremiah read it on Apple Podcasts or on Spotify! I feel like I say this a lot, yet somehow not enough.

I mean, goodness, I do.

Which I think is code for “I’ll be blowing the money on steak and beer”.

I'm not familiar with Barbara Oakley, but I do have some ideas about how the layers of education you describe connect to Vervaeke's taxonomy of knowledge.

I don't pretend to be an expert on that. In fact, I've only read the basics from this post:

https://stefanlesser.substack.com/p/four-ways-of-knowing. But I thought I'd throw some ideas out there, and maybe you and other readers can help connect the dots.

The four ways of knowing are:

1. Propositional knowledge - knowing facts.

2. Procedural knowledge - knowing how to do things.

3. Perspectival knowledge - "knowing what it's like."

4. Participatory knowledge - "knowing that is part and parcel of how we are bound up with something else, someone else, in a process of mutual transformation, reciprocal revelation."

Vervaeke also believes that our culture is currently subject to "propositional tyranny" - i.e., we only value propositional knowledge, and ignore the importance of everything else. That's a problem because piles of facts aren't enough to provide a sense of meaning, which we can only get from the deeper levels. (That seems to match your conclusion from a previous post that "the matter with schooling is that schooling doesn't matter.")

I still don't quite understand exactly what perspectival knowledge and participatory knowledge are, or how they're different. But I think they roughly correspond to what we mean if we say that someone "thinks like a scientist" or "thinks like a journalist." I also have two examples that might help.

First example: A few years ago, I made a New Year's resolution that I wanted to learn more about the world. The implementation I came up with was to read a brief description of a different country each day and record a few key facts for each one (size, economy, political system, etc.). Then I put those notes into Anki to review them using spaced repetition.

I gave up within a week. First of all, adding one country per day was far too ambitious. But the main problem was that when I first started reading about a new country, the things I learned felt fluid and alive. Then as soon as I wrote it down in my notes and started reviewing it, nuances began to disappear, and I could feel my understanding hardening into something frozen and lifeless.

In retrospect, I think the main problem is that the kind of understanding I wanted was perspectival knowledge - what is it like to be from a particular country? And the facts I captured in my notebook were only propositional knowledge. Maybe I would have done better to ignore the facts and figures and write down one key story about each country instead, even though that doesn't fit the spaced repetition model very well.

Second example: My older son is almost two, and in the last few months his language abilities have skyrocketed. So as I watch him, I've been thinking about how language acquisition works.

My first observation is that almost everyone succeeds at speaking and understanding their native language fluently. This is so commonplace that it seems unremarkable, until we notice the staggering difference between this and the level that students generally reach in every other school subject. If the average high school graduate were as effortlessly fluent in math as the average first grader is in their native language, most people would declare mission accomplished.

My second observation is that language is intimately connected to the deeper levels in Egan's framework. Language is so important for culture that it's virtually impossible to truly understand a foreign culture without first acquiring some familiarity with the language. (I've observed this directly, since my wife's family is Chinese.) And evolution has also provided us with specific regions of the brain that are adapted for speaking and understanding language (Broca's area and Wernicke's area).

And thirdly, when they learn their native language, people generally do achieve the deeper levels of knowledge in Vervaeke's taxonomy. A native language is an intimate part of who people are and how they interpret the world. And language is also dynamic, as people actively shape it to better express themselves. (I believe this is something like what Vervaeke means by "a process of mutual transformation".)

So to conclude this very long comment, I suggest this statement as a partial solution for you:

The importance of the lower layers in Egan's framework is that we need to understand what people are like, so that we can design our education to connect with that identity to produce deeper levels of knowledge, which is the only way that what we learn can lead to a sense of meaning and purpose.

I still don't know how that design process would work, but it sounds like that's roughly where you think Barbara Oakley's work comes in. What do you think?

I've added A Mind for Numbers to my reading list, so I'm hoping that will fill in some of the gaps for me.

One analogy that comes to mind:

Egan is like a philosopher: defining what a person is, how it came to be, what is its nature

Barbara Oakley is like an engineer: figuring out how to apply hard science to the problem of learning

A cognitive neuroscientist like Stanilas Dahaene is something like a physicist: figuring out the mechanics of how learning and cognition can occur

Philosophy, engineering and physics all help us understand the world from different perspectives, so why couldn't education have similar levels of understanding?