In yesterday’s post, I suggested how we might help kids to play inside stories. And one one example I gave had some odd details:

1. Re-enacting

A teacher retells a story, and members of the class hamfistedly act parts of it out with a Spider-Man mask, a string, and a large pot.

The story I had in mind was “Anansi the Spider and the Pot of Wisdom.”1

Imaginary Interlocutor: Who the heck is “Anansi”?

Only the greatest non-friendly neighborhood spider ever! He’s West African folklore’s great trickster figure — think Loki, Coyote, and Maui.2 He’s got eight legs, he’s very clever, and when he gets over his skis, hilarity ensues.

For each of yesterday’s challenges, I was going to give an Anansi example for each of the challenges… and then realized that would make the post way too long.3

But examples are useful, gosh darn it! So I’ll sketch out my notions of how yesterday’s example challenges might actually look, if you came upon them in the classroom. (And after, I’ll give you all a challenge for a quite different story — one involving medicine, madness… and MURDER. Comments will be open to all subscribers.)

Oh!

If you don’t know this particular Anansi story, (1) you should, and (2) you can watch a two-minute animated version of it on YouTube. (It’s not the only quick version of it; they all differ quite a bit on the details. Let’s all say it again — we never tell the same story twice.

If you visit a classroom, you might see…

2. Simple summaries

A kid re-telling the story to another in just one sentence:

Anansi discovers wisdom can’t be hoarded.

…in two sentences:

Anansi tries to squeeze all the world’s wisdom in a jar.

He learns that true wisdom lies in sharing knowledge.

…and in three:

Anansi is selfish.

He tries to hoard wisdom, fails, and he looks ridiculous.

This makes him get TRUE wisdom.

Then, a kid summarizing the whole story in three or four words:

Anansi gets wiser.

3. Dissecting

A student listing out all the characters, and what they want:

Anansi — monopolize wisdom

His son — help his father

All the people of the world — to have technology

The sky god Nyame — be generous (or is it to make Anansi look like a fool?)

A student filling out a sheet of what the main character attempts to get what they want, how that fails, and how they try again:

Anansi wants to be the wisest person in the world

He gets a pot of all the wisdom… but is afraid someone will steal it

He climbs a tree to hide it… but isn’t smart enough to climb the tree

His son gives him great advice… but then Anansi realizes he’s not actually wise!

4. Switch the media

A kid drawing a single scene of the story on paper:

A kid turning the story into a poem that emulates the style of another the class has learned:

Anansi, with wisdom, did plot,

To keep it all in a big pot.

He climbed, then saw clear,

His son, wise and dear,

And down fell the wisdom he got.

(Credit: Chat GPT, and a bit of sustained prompting.)

5. Point of view

A student re-telling the story from another character’s perspective:

ANANSI AND THE POT OF WISDOM

(as told by the people of the world)

Once upon a time, the selfish and stupid Anansi decided to hoard all the wisdom in the world. We all laughed as we watched him trying to collect it in a big pot. Of course, Anansi was greedy and didn't listen to others, not even when his own son tried to help him.

When he tried to hide his pot up in a tree, he dropped it, and it broke, spilling wisdom everywhere. THANK NYAME! We, the good people of the world, found pieces of wisdom scattered around and shared them with each other. This made everyone smarter and helped us work together.

6. Characters

A student doing a psychological study on the main character:

Anansi’s Myers-Briggs Type is ENTP: he’s Extraverted, Intuitive, Thinking, and Perceiving. My evidence?

Extraverted: Anansi is social, engaging with others (even if it’s for his own gain), and not afraid to be in the spotlight.

Intuitive: He looks beyond the present, focusing on future possibilities. His plan to hoard all wisdom shows a focus on big ideas and future implications, albeit misguided.

Thinking: Anansi's approach is primarily logical and strategic. He is driven by the objective of gathering all wisdom, showing a preference for thinking over feeling when making decisions.

Perceiving: His actions exhibit flexibility and spontaneity. Anansi is adaptable, willing to try different methods to achieve his goal, such as attempting to climb the tree in various ways.

He’s also a definite Slytherin, and a probable Gemini.

A student swapping out the main character with another character from a different story:

SOCRATES AND THE JAR OF WISDOM

The god Apollo gave Socrates a jar marked “ALL THE WORLD’S WISDOM”.

“Wow,” said Socrates, “I wonder what’s inside!” He opened it… only to discover it was completely empty. He realized that the gift he had been given wasn’t wisdom itself, but a sacred task to collect the world’s wisdom.

“No trouble,” Socrates chirped. “I’ll just head to the marketplace!”

There he talked with many experts in their fields… only to discover that they were fools, pretending understanding of the foundations of their work, when in truth they knew nothing.

Then they killed him, and they lived happily ever after.

7–10: Setting, Plot, Genre, & Theme

These are some of the deepest challenges. They require a person to think carefully about the human meanings of the story, alter them, and think though how the story can still work.

Aaaaaaand I’m going to skip ‘em. (I’ve got an essay about mushrooms to finish! You’ll thank me later!)

But right now I want to point out how far the other challenges have already taken me in understanding this story.

Imaginary Interlocutor: How far, Brandon?

At the start of this, I was frankly regretting my choice of picking the Anansi story — it seemed like I couldn’t find its emotion core.

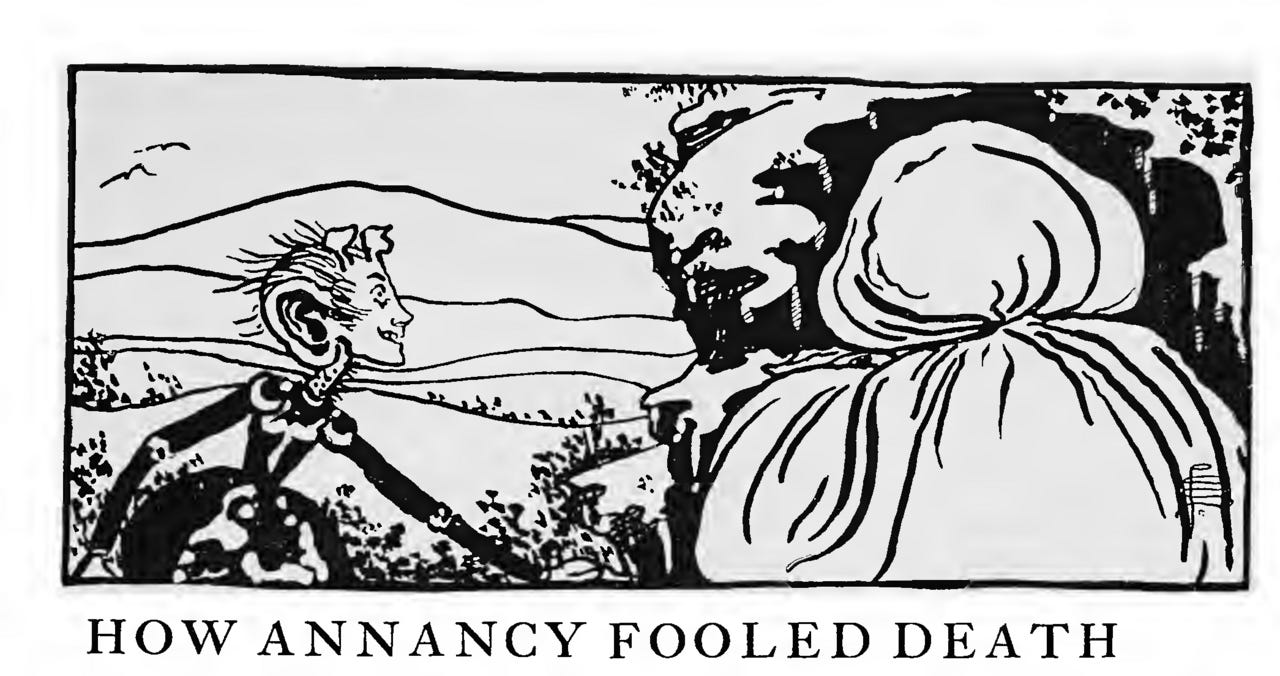

(Traditional stories, in my experience, are especially like that. Whether I’d be reading stories in college from the Irish Gaels, the African Ashanti, the American Navajo, or the Polynesians, I usually found them boring. I felt bad about that. What about the culture, I wondered, was I missing? My working hypothesis now is that the stories I was reading were written down. They were told to an outsider, stripped of context, and printed as stand-alone works — treated as sunflowers instead of bougainvillea. My hunch is that we should understand the versions of traditional culture’s stories that we find in books as skeletons, and understand that it’s our job to give them life.)

Going through these challenges forced me to find the story’s humanity. The summaries set the stage — I couldn’t just repeat someone else’s words; I had to make them my own. Dissecting the story made me realize that the intentions of the Sky God might not be entirely kind. Switching the media (the drawing and the poem) helped me actually feel the story for the first time. Adopting a different point of view made me realize what a jerk Anansi is, which led to my “psychological analysis” (a character challenge) being so negative. All this culminated in my insight that Socrates was a kind of anti-Anansi — a trickster who ends up infuriating people by trying to share wisdom, not steal it.

Ladies and gents: I think this really works as a way to dive into story.

Anansi meets Ignaz Semmelweis

Wanna take a turn? I invite anyone to try any one of the story challenges — either one I’ve already done, or one of the ones I’ve skipped.

And I’ll give you two choices: you can tackle “Anansi and the Jar of Wisdom”, or take on the story of Ignaz Semmelweis.

I.I.: Semmelwho?

Oh, you don’t know Semmelweis? Here’s a teaser: Ignaz Semmelweis is NOT the reason we wash our hands with soap.

He was a Hungarian who lived in the middle of the 1800s. He was a doctor at among the greatest hospitals of the age — the Vienna General Hospital. He’s famed not for his prowess at surgery, but for his answer to a simple question: why were the mothers dying?

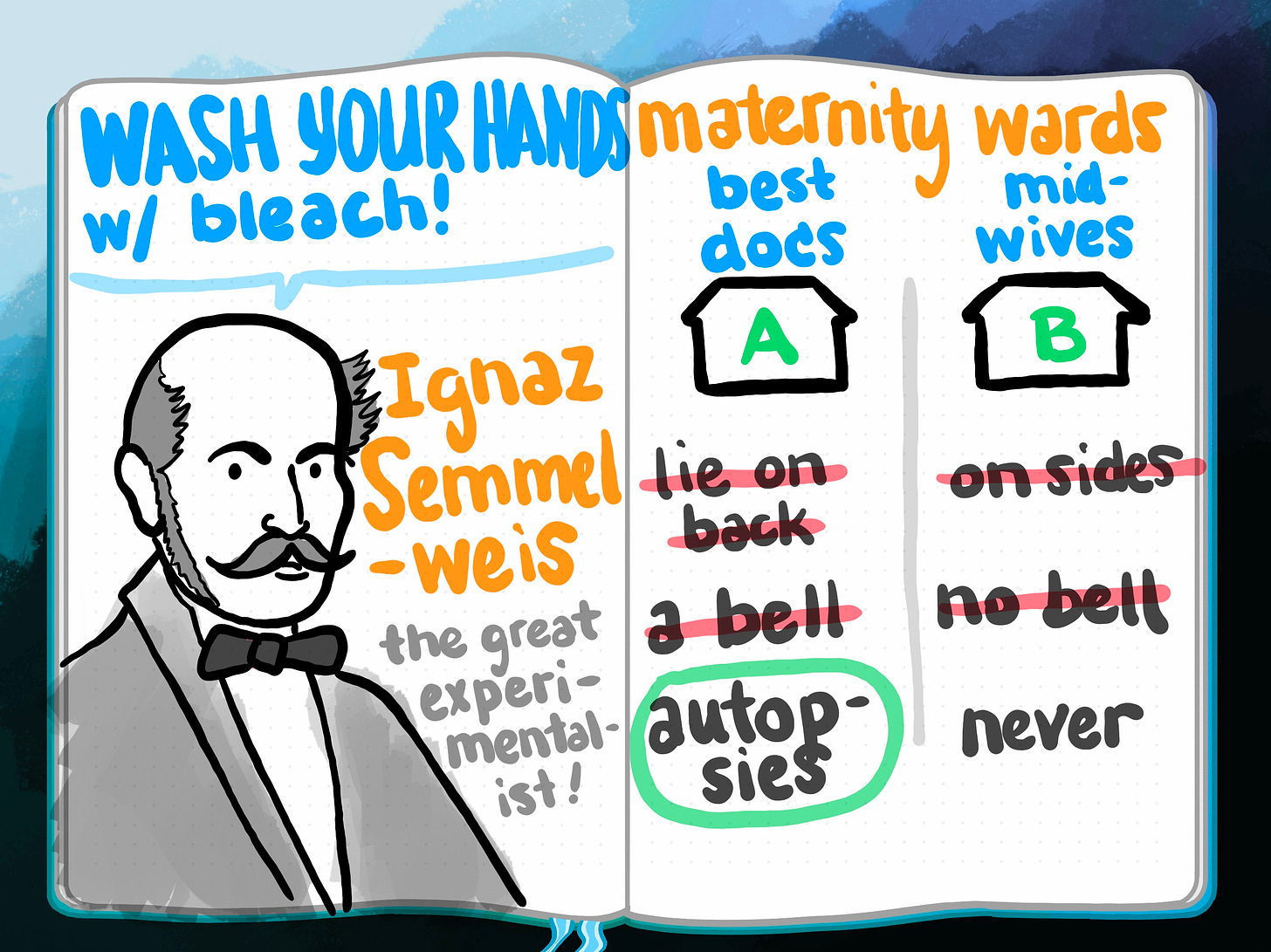

He worked in the maternity ward, which had two buildings. In one, the brilliant doctors, ambitious and philosophically educated, equipped with the most up-to-date anatomy, delivered babies. (These were people who daily participated in autopsies, just to stay on top of their game!) In the other were midwives.

One of the buildings had a low mortality rate: only around 2%.4 The other’s ranged from 10% to 20%. The way the women were dying was especially terrible: pain followed by swelling followed by smelling.

What was going on?

Semmelweis and a friend set themselves to answering this. They chronicled the differences between the two buildings, and experimented — to no avail. To get some perspective, Semmelweis took a vacation in the countryside. There, he received the terrible news: his friend had died. Beforehand, he had experienced pain in his hand, followed by swelling, followed by smelling.

He also received a clue: soon before that, his friend had nicked himself performing a morning autopsy.

Semmelweis realized that he had been looking in the wrong place: the problem wasn’t what was happening inside the maternity ward, but what had been happening before the doctors entered it: they were touching dead bodies. And while they were washing their hands with water, it must not be enough — something was catching a ride on their hands, and being taken into the birth canal.

He soon had the doctors in the maternity ward washing their hands with chlorinated water. And the mortality rate shot down:

Then he was called into the office of the hospital administrators. It was very kind, they said, that he had volunteered to lead the experiment, but now it was time to stop it.

Semmelweis protested: this was working! New mothers were living, who otherwise would have died!

Yes, they agreed, the death rate was down. But correlation isn’t causation, and the best medical minds of the era were agreed on what caused sickness: bad smells. A doctor, they emphasized, did not smell. Implying so was offensive.

Semmelweis left the hospital, deciding to take his crusade on the road. Over the next years, he would give lectures in halls throughout Europe… but was met with disbelief and scorn from his fellow doctors. Surely he wasn’t implying that they were dirty? (“A doctor is a gentleman,” one said, “and a gentleman’s hands are clean.”)

No, he replied, it’s not dirt — it’s “necrotic particles” — little bits of death that were slipping from corpses to living bodies. This made little sense to them — and, in fact, we recognize today that it’s entirely wrong, too. Bacteria aren’t bits of death — if anything, they’re bits of LIFE.

He grew angry. He publicly branded those who wouldn’t follow him as “murderers”. He poured himself into writing articles that he struggled to get published and a book few read.

Finally — there’s no kind way to say this — he lost his sanity. There may have been other factors: some historians suggest syphilis, others Alzheimer’s. But he was tricked into entering an Austrian asylum and disallowed from leaving. He plotted his great escape, and when he made it was caught and beaten. He died in August of 1865 from the same infection that he had learned to prevent in the new mothers.

Eventually doctors would rediscover the wisdom of washing one’s hands with something more powerful than water. And when they would — about fifty years later — it would cause one of the greatest upticks in human life recorded in history.

But Ignaz Semmelweis is NOT the reason we wash our hands with soap.

Your turn, if you’d like

Now, pick a challenge (see yesterday’s post if you’d like a breakdown of #7–10) and go with it! Comments are open to everyone this week. (And if you’d like to understand more of these stories, various animated versions of both can be found on YouTube.)

Which I understand was the working title of one of the Harry Potter books.

Except, still, with more legs.

If I’m saying something’s too long, you know we’re in trouble.

Yes, this would be monstrously high now. It was the 1800s; everything was terrible.

This one was just fun:

There once was a man from Budapest

who compared which ward could do the best.

He compared the physicians

with midwife clinicians.

The doulas saved more lives- who'd have guessed?

One sentence:

A man observes that commonly-accepted best-practices have worse outcomes than less socially-esteemed ones.

Two sentences:

Semmelweis discovered that doctors were unintentionally killing their patients. He thought that autopsies were spreading little pieces of death.

Three sentences:

He ruled out all the other possibilities. Washing hands seemed so simple. Unfortunately pride prevented them from accepting it.

Three words:

Oh, the irony!

This really made me think about the story much more than I originally imagined. I also liked trying to use different lengths to show different aspects of the story.