1. A problem

Spoken English is a charming language, but its spelling system was forged by the hands of Lucifer himself.

The letter ‘G’ can trigger two sounds, the /ee/ sound can be triggered by eight different letter combinations.1 The story of how we got into this waking nightmare is tortuous, but it starts with a simple fact: the English alphabet wasn’t made for English.

2. Basic plan

Teach kids the story of the alphabet. Teach it as a series of small stories, and scatter them through the early years, sometimes linked to other things the students are learning, sometimes just thrown in for the heck of it.

Whenever possible, kick off the stories with simple questions.

Connect this up to the history kids learn of the ancient, medieval, and modern worlds.

Focus the imbecilic, the brilliant, and the absurd aspects of the English alphabet.

3. What you might see

In grade 1, kids asking why we have both a ‘C’ and a ‘K’.

In grade 2, kids learning why we have a silent ‘E’.

In grade 3, kids hearing about the sounds Latin doesn’t make.

In grade 4, kids examining the deal with which words end in ‘LE’ (“put the simple purple bottle on the circle table”), vs. which end in ‘EL’ (“cancel the novel tunnel — the rebel vessel is in a camel duel!”).

In grade 5, kids discovering the Greek, the Phoenician, and the Proto-Sinaitic alphabets.

In grade 6, kids experimenting with the letters that English has lost.

In grade 7, kids exploring why ‘GH’ makes the ‘F’ sound… or can be totally silent.

In grade 8, kids learning the lore of the letter ‘Q’.

In high school, kids having an impassioned debate over spelling reform.

4. Why?

We should understand our tools.

Look: maybe half of schooling boils down to saying “hey kids, let’s use the alphabet!” It’s almost the only thing we do. And it’s the source of endless frustration. Most kids’ handwriting might be described, optimistically, as “legible”, and they take little joy from it. Their spelling strains the skill of even the most advanced autocorrects. Reading comprehension lags behind nations whose alphabets fit their languages.

In this situation, to not tell the weird, sometimes hilarious stories of what this alphabet thing is seems an odd choice.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

We’re currently agog with large language model AI’s; historically, we make a big deal out of the printing press. But the first real alphabet was more revolutionary than either.

By convention we say that the first “alphabet” — the first set of symbols that described spoken language, and started with an ‘alph’ and ‘bet’ — was one we find scrawled on statues in the Sinai peninsula by some now-forgotten Semitic laborers. What’s curious to our modern eyes, however, is that it’s incomplete — it’s missing any vowels. The whole thing is consonants.

To be clear, this “Proto-Sinaitic” alphabet was an enormous improvement on what preceded it. Its thirty-or-so symbols replaced the thousand symbols that made up Sumerian cuneiform. Learning to read cuneiform was the work of a lifetime; no one outside the small set of priests and scribes could ever hope to master it.

And yet, lrnng t rd a mssg wrttn wtht vwls tks hrd wrk.2 Worse, there’s no way to know if an author meant to write “bat” or “bet”, “cart” or “court”, “leap” or “loop”, “fraction” or “friction”. This limited how much help such an alphabet could be.

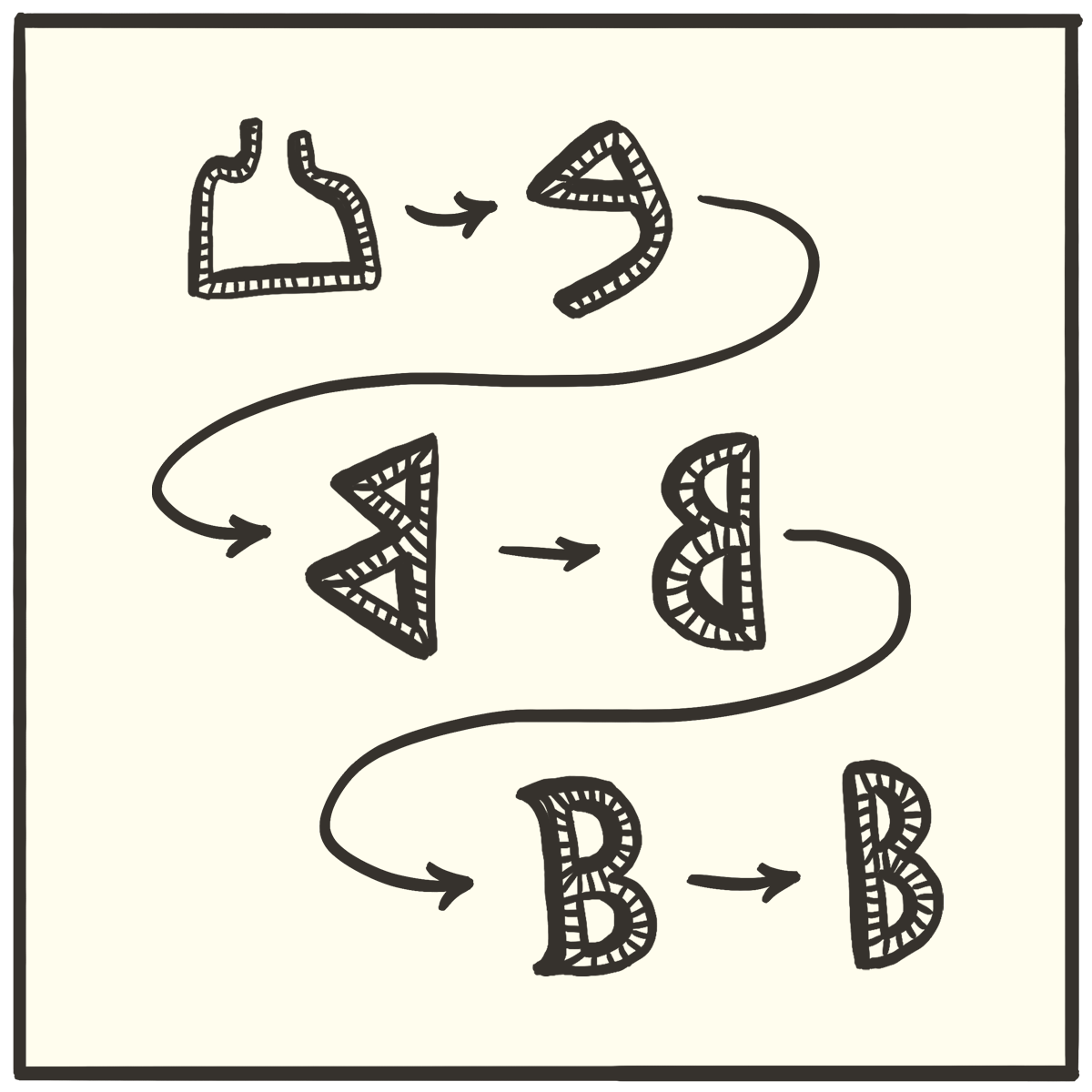

And then came the revolution. A Greek who was learning the Phoenician alphabet noticed something curious — it had seven consonants that the Greek language didn’t need: α, ε, η, ι, ο, υ, and ω. These letters, the now-forgotten linguistic entrepreneur realized, could be repurposed to represent Greek vowel sounds:

α became /a/ (“father”)

ε became /e/ (“pet”)

η became /ay/ (“they”)

ι become /ee/ (“seen”)

ο became /o/ (“not”)

υ became /ü/ (“uber”)

and ω became /ō/ (“no”)3

With this tweak, something new came into being: scribbles that could encode speech.

This revolutionized thinking. In a historical instant, reading and writing were opened to the masses. Many more people were able to pull from (and contribute back to) the hive mind. And the next few generations witnessed perhaps the greatest intellectual explosion the world has ever seen — a flourishing of history, math, philosophy, and more. Historians refer to it as “the Greek miracle”.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Surely the alphabet would have been invented somewhere else, eventually.

Perhaps. But don’t forget how slow written language conventions are to change. (For example: English stil insists on stiking too uh un-fonetik speling sistum, eevun tho basiklee evreewun ugreez it wud bee gud too fiks it. Thuh insentivz ar missalaynd — thuh peepl hoo find it hard too lern hav difuhkultee geting thare poeent uhkros.) Why would a scribe buck his profession to simplify his system, when success would mean he’s out of work?

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

This is accomplished pretty easily by the Mythic tools of 🧙♂️STORIES and 🧙♂️RIDDLES. Romantically, it lends 🦹♂️HUMANIZING KNOWLEDGE they can reflect on every day. (What do these weird emoji mean?) 🤸♀️🧙♂️🦹♂️👩🔬😏

6. This might be especially useful for…

The sort of kid who otherwise might be drawing crude images of specific anatomy in a math textbook, realizing that whenever he writes a capital letter ‘A’ he’s drawing THE UPSIDE-DOWN HEAD OF A DECAPITATED OX.

7. Critical questions

Q: Do you really think this can improve literacy?

Yes.

Q: But this seems inefficient. Wouldn’t it take away valuable time we could spend drilling them on phonics?

I’m not personally opposed to drilling — but it has a decreasing return on investment, because students turn off their brains.

One of the most counterintuitive aspects of Egan education might be that the most efficient uses of educational time often look inefficient.

Q: Oh, jeez, are you becoming one of those “don’t worry about outcomes, let the kids relax” people?

I don’t think so. A lot of interventions (I’m thinking about ones that come from Educational Progressivism) really are wastes of time. The “inefficiencies” that end up being efficacious are the ones that help press the “this matters!” button in kids’ brains. And as any cognitive scientist can tell you, stories can do that.

Feeling fighty? Want to disagree? Assuming you can do so politely, do it! You just need to be a subscriber. (And, for the next few weeks, not even a PAID one. Wow.)

8. Physical space

At home

We’ll be making timelines of Big History that will spiral around the room; we’ll want to put up some of the key moments in the evolution of the alphabet.

In a classroom

The above, plus (perhaps) some materials at a Challenge Station where kids are prompted to try writing in one of our ancestral alphabets, or to write a message without vowels and see if a friend can read it. And putting up a poster about the alphabet’s evolution would be pretty sweet.

9. Who else is doing this?

I don’t know anyone who does this at the K–12 level, but I bet they’re out there, because knowledge of this seems to be trickling down to we lay folk: fonts, geeky t-shirts, and more. I found out about Proto-Sinaitic when I happened upon a children’s book titled Ox, House, Stick: The History of Our Alphabet. RECOMMENDED, and your library probably has it.4

The (wonderful wonderful) YouTube channel Useful Charts has made a poster that lives up to the channel’s name:

How might we start small, now?

Spend a minute staring at the above chart, and try to guess what the letters ‘L’, ‘M’, and ‘O’ are supposed to be pictures of.

10. Related patterns

This fits snugly with Other Alphabets°, and also within Egan’s plopping of Big History° at the center of all education. Leading with a riddle makes this like Secrets and Revelations° for language. It’s similar to Origins of Words°, and probably would benefit from Teaching the IPA°.

Afterword:

A reader and supporter suggested — and this is the kind of feedback that I’m really thankful for — that I might be putting so much fun into these pattern-language posts that it’s getting in the way of ease of reading. I’ve been thinking hard about this, and haven’t yet come to any conclusions. (I like writing the fun stuff, but I also like writing future essays and whatnot. Everything’s in contention for my writing time…)

So, a poll! It’ll stay up for a week. It’s not a vote, exactly — I’m not promising to follow whichever side wins, and I’m not even sure I could change my style if I try — but I’ll take your thoughts seriously. (Feel free to put in a comment below with more thoughts and ideas.)

Oh — my family and I will be traveling for the next couple weeks to see the eclipse, so posts might be hit or miss.

At the scenic beach, Steve the Happy Thief received a unique prize — the key to a theme park! — thereby demonstrating how widely whimsy through life can weave. (See?)

T b fr, Smtc lnggs dn’t ln s hvly n vwls s Englsh ds.

Note to my many friends who are orthography nerds, Greek geeks, or both of the above: these are probably wrong! I’m provoking you! This is an intentional micro-aggression! (If you could write a comment to help me improve this, I’d be grateful.)

Ridiculously, I had spent two years learning modern Hebrew, and never noticed that its first four letters are A (א), B (ב), G (ג), and D (ד).

I have more than one thing to say about this post (no surprise...lol). In my first snippet of time I have for a comment, let me just say that mnemonic sentences for learning the multiple spellings for various English sounds are awesome, but IMHO so much more effective if your sentence is in the approximate order of frequency for how often it is found in English words.

Sometimes I have quibbles with the sentences we were taught in the Orton-Gillingham training I took, but they are decent.

Spellings of E taught at the "basic" level: e, ee, ea, y, e-e, ie, ei, ey

Sentence: We need meat and candy for Pete and his chief weird monkey.

(i as a spelling for e is not taught at the basic level in the training I took, which is an annoyance to me, since it is relatively common - I had a whole argument with my trainer about this, but she wouldn't back down and insisted it needs to be taught only to advanced students who are ready to learn about "connective i" with suffixes...despite words of Italian and other origins with i representing long e at the end of words).

If a student is trying to decide a spelling choice for the words, they can say the sentence, write out the spellings in order of frequency, and try the spellings in that order (it works better if they have also been taught placement rules - such as e is only going to say long e by itself at the end of a syllable or short word).

Today's xkcd is about the cursive alphabet...what timing! https://xkcd.com/2912/