Our goal, once again, is to craft a language curriculum that (1) ensures nearly every student enters high school actually speaking an additional language, and (2) integrates language learning in a way that enhances every other subject — humanities, science, art, math, language, and practical superpowers.

This is ambitious! We’re designing this for homeschoolers first, but with solid feedback, I’m hopeful we can adapt it for classrooms too.

In part 1, I laid out the first three elements:

unveiling the magic of language to kids by “tasting” multiple languages,

adopting a language as a whole family, and

mastering your language’s sounds, so you have near-perfect pronunciation from the start.

In all of this, we’re hewing close to the approach that Gabriel Wyner laid out in his book Fluent Forever, which is in my opinion one of the world’s few perfect books.

Here, I’ll lay out how I imagine Eganizing Wyner’s method to

learn vocabulary.

This one packs a punch, so I’ll save our final step of learning grammar for a later post.

Just as a reminder, this won’t take us all the way up to fluency. Heck, it won’t even take us to “I could survive in the country for a week by ordering tacos”-level proficiency. That’s the goal for middle school (grades 5–8). As I see it right now, the goal for elementary school is to prepare the whole family for the more-intensive language learning of those years, and to be hungry to do it.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Anything you’d change from the first post?

Yeah — I’m increasingly interested in the how valuable planning to visit another country (and then actually visiting it) can be for a family. So I’m leaning toward recommending that we plan to visit the country twice — once at the end of fourth grade, and once at the end of eighth grade. Obviously, whether this is a good idea will vary from family to family, but I think it’s nice to have the trip not feel forever-far away. Also, there’s something wonderful about going back to a place, to learn about it.1

3: Eat a thousand words

Here, you’ll learn a super-efficient method of learning words, actually learn a thousand words (or more), and start using them every day inside your home. At the end, I’ll lay out how this approach isn’t just a crazy-effective method to learn language, but is deeply Egan.

The words

I.I.: Which words are we going to learn?

First, the 625 most common nouns, pronouns, verbs, and adjectives in your adopted language, as well as any other words that you’d like to learn.

Thanks to Zipf’s Law, knowing just the 625 most common words will mean that you’ll recognize about 75% of the words you’re hearing in conversation or reading in a book. Happily, Fluent Forever lists those words in Appendix 5. (The app, of course, just builds those in from the get-go.)2

I.I.: Just nouns, pronouns, verbs, and adjectives? What do you have against prepositions?

Function words like of, the, in, and are don’t translate as cleanly between languages as content words do. We’ll tackle them differently — more on that in the next post.

Moreover, nouns, verbs, and adjectives are easy to visualize and remember: grass, shove, tall, and so on. (Pronouns are perhaps less so, but they’re so few and so useful that it makes sense to start learning them up front.)

How we’ll learn them

I.I.: How’re we going to learn these common nouns, and so on?

By special-made flashcards that take full advantage of the weirdness of human memory, plus spaced repetition.

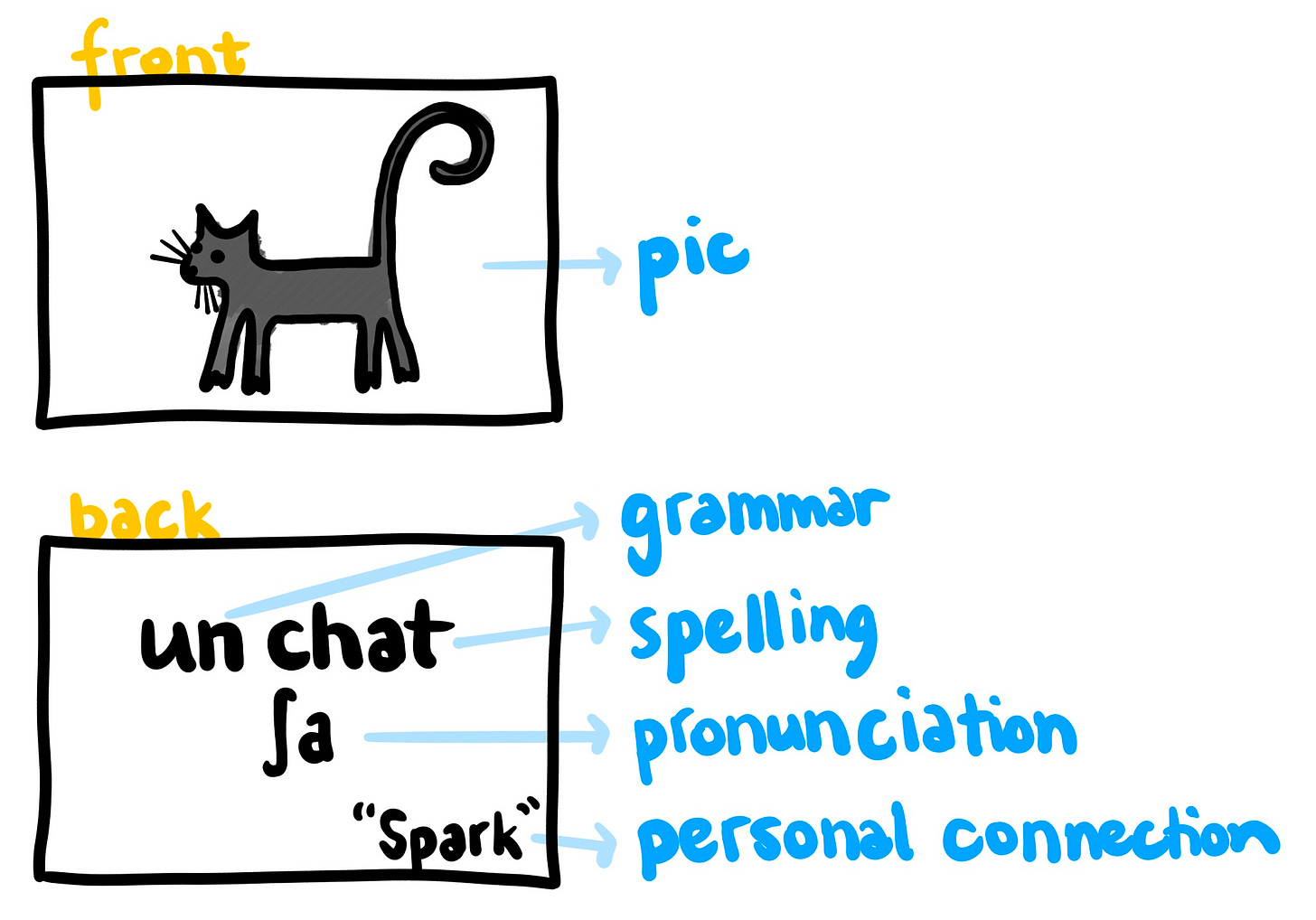

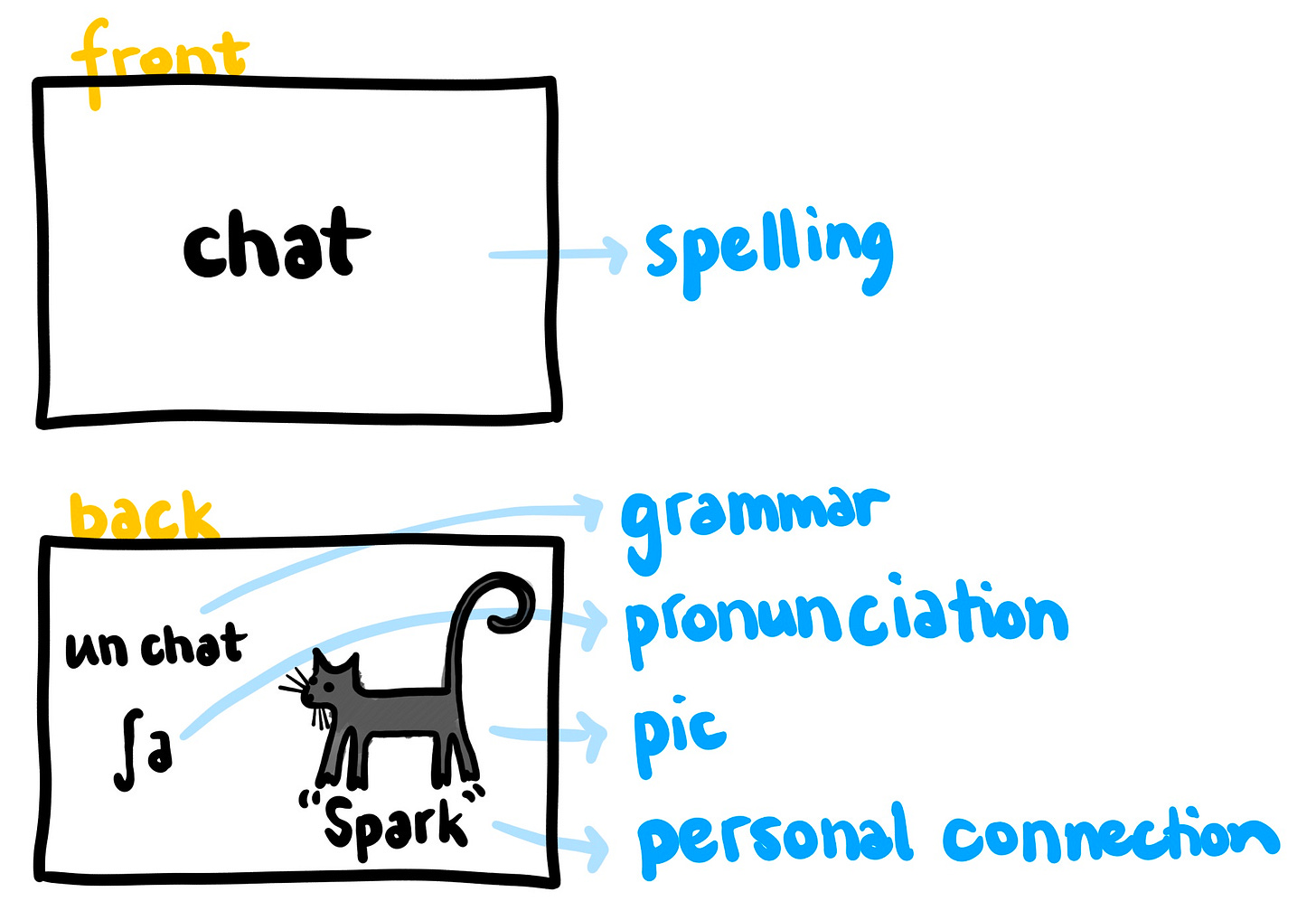

We’ve all had the experience of cramming things into our brains, and being frustrated to find them falling out. We’re going to avoid this, here, by taking advantage of🧙♂️VIVID MENTAL IMAGES. If you’re learning that the French word for “cat” is /ʃa/ (roughly, “shah”), you’re not going to write the word “cat” anywhere on the flashcard. Instead, you’re going to put an image of a cat on the card.

I.I.: Why would that matter?

Our ultimate goal is to think in your new language. You don’t want to forever be translating the English in your head into a sentence in your new language. And one of the discoveries of cognitive science is that, to a surprising degree, your mind’s native language is images. We can get to fluency faster by linking new words directly to images, and keeping the vocab cards English-free.

I.I.: What images are we going to use?

Crucially, images from the culture of the language we’re learning.

One fun fact about languages: in some sense, no word perfectly translates between them. In practice, most words share a close-enough meaning that we don’t mind this — the French chat is basically the English cat. But more often than you might think, there are wrinkles.

For example, a bilingual dictionary will tell you that the Russian for word dog is sobaka. What it won’t tell you is that Russians don’t think about dogs the same way Americans do. English speakers talk about dogged determination, but Russians don’t talk about sobaka-ed determination. In Russian, sobakas don’t yip or nuzzle or save Timmy from the well. Instead, they devour you when you pass out. From Chapter 4:

When I was in Russian school, we watched a movie where the protagonist got drunk, forgot his shotgun, and got eaten by sobakas. Seriously. In English, dogs are man’s best friend. In Russian, sobakas leave behind empty, tooth-marked boots.

Wyner calls this “the symphony” of each word. It includes “a cacophony of images, stories, and associated words”. When you see the word dog, your brain is going to be predicting more words to follow. When a Russian sees sobaka, those are going to be very different words. When you choose your picture for your vocab card, you’re going to be trying to tap into that.

Doing this will make understanding your language easier, because your brain is a prediction machine: when it sees a word, it starts predicting which words will come after, so you can readily make sense of what you’re hearing. (Doing this will also help us achieve our deeper Egan goal of not merely learning another language, but entering another culture.)

Wyner has a lot to say about the specifics of how to get these images (hint: do a Google Image search, but from other countries’ Google sites — like google.es, google.fr, or google.it). The details can be found in his book, or experienced by using his app.

I.I.: How else will we be securing these words in our memories?

By writing in the precise 🤸♀️SOUND of the word (with IPA pronunciation), and by adding a personal connection.

The general strategy here is that the more connections any memory has in our minds, the more effortlessly it’ll be remembered. And this is because of how your brain actually works. In your three-pound brain, there’s literally a web of neurons that stores the audio recording of /kˈat/, and another web that houses the concept of your particular pet cat. There are other webs that contain images of kittens playing, and one that holds the feeling of the warm, floppy weight of your grandma’s cat plopped on your lap. When you think of a “cat”, many of these light up, and make it easier for the others to, too.

This is what a word is, in your brain. It’s not a discrete thing. We want to build vocabulary with that in mind.

I.I.: What’ll these cards look like?

To really lock these in, you’ll want to make multiple cards for each word. The first should put the word first, and ask you to say it aloud and recall what it is:

And the second will give you a picture, and ask you to produce its name:

I.I.: This would seem to take a long time to do.

Indeed! But it’s faster than constantly re-learning what you’ve forgotten. It’s also a master class in the ART OF MEMORY°: how to get information to actually stick in your brain.

And, according to Wynne, it’s also enjoyable! I can imagine that — which each card you’re personalizing your knowledge of an alien system, and tangibly moving forward on a quest. But, of course, the proof of the pudding is in the eating; if anyone has already done this method, and is willing to report, please tell us in the comments.

I.I.: How quickly will we learn them?

Remember, we’re taking this slow. My hunch is that this would work well:

in 1st grade, add 1 new word each day

in 2nd grade, add 2 words

in 3rd grade, 3

in 4th grade, 4

I.I.: That’s really slow.

Of course you can add words more quickly if you’d like, but I think it’s imperative (especially at the very beginning) to give each word your time and attention and do it well. Even at that rate, and assuming a 180-day school year, you’ll build up an impressive vocabulary by the end of elementary school:

Grade 1: (180 days × 1 word/day) = 180 words

Grade 2: 180 words + (180 days × 2 words/day) = 540 words

Grade 3: 540 words + (180 days × 3 words/day) = 1,080 words

Grade 4: 1,080 words + (180 days × 4 words/day) = 1,800 wordsWith nearly 2,000 words, according to Zipf’s Law, you’ll likely understand 85–90% of the words in a new text — assuming they’re the most common words.

How we’ll review them

I.I.: And that’s it? Then they stay in your memory forever?

Probably not. To manhandle The Princess Bride:

I suppose “pain” is too harsh a word — actually, it’s the experience we’re trying to avoid! But learning requires work, and a language requires a lot of learning.

There are two ways we’re going to further lock in these words. The first comes from Gabriel Wyner, but is something we’re already putting near the center of Egan homeschooling: spaced repetition. I’ve already written a pattern for that…

…so I won’t repeat it here, except to answer an important question:

I.I.: Should we really write out individual flash cards here? Wouldn’t it be a lot easier to use a spaced repetition app, like Anki?

Probably, and you should consider it. (Wyner’s a huge proponent of Anki, and lays out instructions for how make custom language cards in his book.) But there are advantages to doing it by hand, too:

When you use physical flash cards, you benefit from an involved hands-on arts and crafts experience with each card. This is a wonderful learning experience that will make your cards much easier to remember.

This seems especially true for kids who’ll benefit from this daily authentic practice of handwriting and simple drawing. The choice, though, is up to you. (And you can always start with physical flash cards and transition to digital ones in middle school.)

I.I.: How’d I use this with multiple people (kids or adults)?

If you’re using physical cards, you can go through the deck multiple times, or do it with your whole family at once, and only count the card as having been learned if everyone remembers it. (If one kid — or adult! — is having a hard time, you can do it with them, separately.) If you’re using an Anki deck on the computer, you can simply make different accounts for each person in the family.

How we’ll practice them

But there’s one more way homeschooling families can lock in vocabulary: a years-long, all-family game of Taboo.

I.I.: What?

I’m still working on this idea, and I’d love your thoughts on it. The basic notion is that as you learn each new word, you “taboo” the English version of it. That is, in your home, you’re supposed to use the foreign word, rather than the English one.

I.I.: “Supposed to” sounds dire. What happens if you say the English word? You lose a finger?

It’s a game, not an attempt to recreate the Draconian Constitution.3 These aren’t real-world punishments, they’re wacky in-game limits. Make it fun! Set a clear family goal, create ways for everyone to contribute, and define when the game is ‘on’ (and when it’s not).

I may be writing more about this in the future; if you want to help shape it, throw your wacky ideas in the comments.

I.I.: Won’t mixing words into daily speech just create bad habits — a weird homebrewed pidgin language?

This is actually natural as a stepping-stone: bilingual kids do this all the time (thus creating Spanglish, Chinglish, and Engrish, just to name a few examples). As your family learns phrases, grammar, and full sentences, you’ll transition to speaking more and more of the language.

But as I’ve emphasized before, I’m far from an expert on language acquisition! If anyone sees any potential problems here, let me know.

How this is Egan

This method of learning vocabulary seems deeply Egan to me in three ways.

Way #1: It uses the tools

🧙♂️MENTAL IMAGES is, of course, near the center of Egan’s MYTHIC toolkit. That it’s been used in learning vocabulary for millennia is a testament to the power of these tools.

Way #2: Subjects overlap

For the last century, nearly everyone has agreed that walling off the different subjects was a stupid idea. (“We’re in history. Now we’re in math — stop thinking about history!”) The many attempts to tear down the walls, however, have usually resulted in a shallow, intellectually-indifferent education. The problems with this are most obvious when kids are learning another language. To learn a language well enough to talk with native speakers, you need to practice it in all sorts of situations — not just “when it’s time for class”. The standard methods of language learning are doomed from the start. (The exception, of course, is language immersion schools. Not coincidentally, they tend to actually work!)

In Egan’s approach, we keep the subjects, but knit them together in ways that enrich each other.4 So it makes sense that for language, we’re going to have it take over your home. You’ll be thinking in your adopted language at least a little bit throughout the day. And — like I said in the last post — you’ll be using your language to actually communicate.

Way #3: It captures the deeper reason to learn a language

In Egan education, the purpose of learning something is never just “it’s useful”.

That’s not to say that the things that we do aren’t practically useful for kids. They should be! But Egan’s insight is that “you’ll use this when you’re an adult” isn’t enough to activate the full motivation of 98% of kids. For that, you need deeper evolutionary values, like beauty, bewilderment, and existential questions.5

The Fluent Forever approach gets at all of these, but especially the existential question of “how do my language and culture shape who I am?”

This is what’s going on in Wyner’s approach to learning vocabulary. We’re not just learning a language, we’re connecting with a culture — and traces of the culture are present in their words. By looking at the connotations of each word to native speakers, we’re test-running a new way to exist in the world.

I’ve also stumbled across the genius/madman Kevin Kelly’s tips for travel, which I recommend as fun family conversation. And since I might never again have an organic reason to point to it, Kelly’s Cool Tools: A Catalog of Possibility is one of those books whose glory is hard to describe, but worth just having in your home.

To try to throw cold water on my ardor for Fluent Forever, I’ve looked up critiques for it. Perhaps the best criticism I found was that the most common words don’t perfectly overlap between languages. This seems true, but you’re going to be learning more words soon, so I’m not sure how much force this has. Anyhow, if you’d like to use a list of the 1,000 most-commonly-used words in your language, knock yourself out.

According to Plutarch: “And Draco himself, they say, being asked why he made death the penalty for most offenses, replied that in his opinion the lesser ones deserved it, and for the greater ones no heavier penalty could be found.”

Usually this is “tap into the humanity of the topic by seeing where our knowledge of it came from in the first place.” See ORIGIN STORIES° for more on this. History über alles!

These come from Alessandro, who recently showed me his methods for training teachers in Egan’s philosophy. “Blown away” is a pretty good description of how I felt; we’re talking about how to bring this to a wider audience.

thank you for the post and the interesting perspectives. i'm esl and i've worked as an english teacher for the last 10 years. i got to the 'c2+' level in high school. i worked with kids first and now mostly teach business english. i've also learned french (pretty good) and japanese (a fascinating nightmare).

i love the 'symphony of the word' idea and the explanations with the dogs. i think that is EXTREMELY important, and should guide the whole learning process more.

this is maybe the most interesting part of learning a different language - it's not that we describe dogs with a different sound, but they are actually a different concept. this happens A LOT and is extremely important as it, in a way, teaches empathy and understanding; a 'dog' might be a very different thing for someone else. it's a more practical version of theory of mind, and a window into how different cultures are.

if you go with the 'learn XXX most used words and their translation' method, you'd learn that 'I' = 'watashi' in japanese. that's first of all, not true, second of all, really boring compared to the truth.

also, i had some success teaching, and the single most important variable was the motivation of the learner. it'd always be very slow or almost impossible if somebody was learning to impress another person, or 'just in case' or to 'order a meal in a restaurant'. however, i had some rocket speed progress when english was a door to some forbidden fruit (for kids) or a clear path to more money (for adults). e.g. i got a kid from failing the english class to being the best in school by watching and discussing 'breaking bad' with him.

when it's interesting and useful, it goes really, really fast. i see this is a big part of what you describe, i just wanted to highlight how big the difference can be, and that you should build the whole process around it. flashcards, vocab lists, schoolbooks are NOT interesting, and therefore almost always slower than presenting the kid something that they want to understand (i think this was a part of your post on presenting a kid with a piece of code). the reason and motivation for learning needs to be always in the centre. i feel like this might have something to do with the american failure to learn a second language that you describe. i believe it stems from a sense of superiority and lack of visible gain - 'what can i learn from these people if my government has dominated them militarly? clearly their model is worse'.

i learned a lot about teaching doing the celta course - you might want to look into their method, aimed at transforming native speakers into teachers in a month.

no self promotion, but i'm working on an app building around immersion, translation, and 'binary search'. the idea is you see a phrase and two possible translations and choose the better one. instead of clearly assigning X = Y, we learn what the sentence can mean, and what it doesn't, and narrow the actual meaning. there are no vocabulary lists, no other exercises, the user is expected to just immerse themselves in doing a lot of exercises quickly, like interactive, phrase-based anki.

i hope to use data + language models to make the sentences really perfect for each user. so you don't learn "100 most used nouns". you learn exactly the phrases you need based on your bio/social media/whatever context.

i'd love to hear your opinion on that, and how you think it could be improved.

thanks for your takes and good luck with learning! i believe there is no better adventure than feeling sapir-whorf on your own skin. i also strongly agree that the purpose of language is to communicate with other humans, so forums, chats, letters, etc might be a better idea than flashcards or some kind of memorisation with no partner.

I'm finding all of these language reflections fascinating (I just know about your work tangentially from a friend doing Science Is Weird and loving it, which is how I discovered your substack) -- my focus is Latin and Greek, so pronunciation is less a concern of mine, but I am a big advocate of fluency and meaningful language use, and one strategy I use is proverbs for vocabulary building; don't just learn a word -- learn a proverb. I'm currently doing daily proverb emails for Latin and Greek students (you can see blog stream at LauraGibbs.net), and I would be glad to volunteer to do proverb vocabulary banks for Italian or Polish if anyone adopts either of those languages (I speak both), and at a stretch I could also do Spanish and Russian (which I read but don't speak). And if anyone is interested in Latin or Greek, I am glad to volunteer my services (I'm currently developing a Latin course for a friend: LATIN WITHOUT CHARTS, doing case-by-case instead of declension-by-declension as Latin textbooks usually do, and do badly...). Best wishes for all your work! Laura (I'm at laurakgibbs@gmail.com)