1. A problem

Some fundamentals of arithmetic are notoriously challenging for human brains. (Think multiplication tables. Heck, try to remember back to how long it took to learn to count!) And when those steps aren’t automated, everything in math becomes harder.

2. Basic plan

Weave the power of music into math: create little poems for the basic counting patterns. And cheat: use an AI to draft it for you.

3. What you might see

Fingers snapping, hands clapping, and mouths chanting, say, the multiples of seven:

Seven, fourteen, through the ferns, Stegosaurus takes her turns. Twenty-one and twenty-eight, Triceratops comes into the gate. Thirty-five and forty-two, Velociraptor joins the queue. Forty-nine and fifty-six, Brontosaurus plays his tricks. Sixty-three and seventy, T-rex laughs, “You can’t catch me!” Seventy-seven, eighty-four, Dinosaurs stomp, hear them roar!

Imaginary Interlocutor: Brandon, that’s — that’s the worst verse I’ve ever read, and I’m on #PoetryTwitter.

RIGHT? The beautiful thing is that for this to be helpful, the poem doesn’t need to actually be good. (Though if you’d like to improve it, see below.) And how about this one? (See if you can figure out what it’s helping you remember.)

One and two, Through sky so blue. Four and eight, The Moon pulls our weight. Sixteen, thirty-two, Mars enters into view. Sixty-four, one-twenty-eight, Through Jupiter’s storms, we navigate. Two-hundred-fifty-six, Saturn’s rings — take some pics! One thousand twenty-four, Past the Kuiper belt we soar. Two thousand forty-eight, Far beyond the solar gate. Four thousand ninety-six, Into the Milky Way we mix.

4. Why?

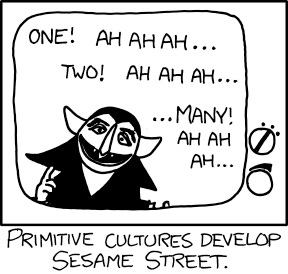

We live in such a math-saturated world that it’s hard to realize that numbers aren’t a thing human minds naturally do.1 Heck, numbers larger than 1 and 2 seem to evolve rather late in language:

But poems? Poems probably go back to the beginning of language. As a species, we fall into using rhyme and rhythm much more naturally than a base 10 number system.

We should play to our strengths.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

You probably know “one, two, buckle my shoe”: people have been using rhymes to practice counting for a while now.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

🧙♂️RHYMES and 🧙♂️RHYTHM are fundamental MYTHIC (🧙♂️) tools — they come with language. Leaning on them allows us to more quickly build our understanding of abstract math patterns, which is almost definitionally PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬). (What do these weird emoji mean?)

6. This might be especially useful for…

The mass of adults who still don’t feel comfortable with “seven times eight”, though they’ve spent God-knows-how-long trying to pound it into their heads.

7. Critical questions

Q: Brandon, this isn’t math. This is the OPPOSITE of math! This gets in the WAY of real mathematical thinking.

So I think you’re actually right that learning the names for numbers isn’t math — but that should make us feel fine about using poetry. Number-names are fairly arbitrary — and nothing’s as good as getting us to remember arbitrary words as poetry.

Q: But what about the sevens times table? It’s really important that kids UNDERSTAND how sevens work.

If it is, then I’d love to know how sevens work, too! They seem the proverbial red-headed stepchild in our base 10 number system: the pattern for fives is obvious; the pattern for nines is amazing. But sevens? Sigh.

Q: Okay, maybe it’s fine to use this for sevens. But you shouldn’t use it for other numbers — it’ll get in the way of understanding the deep patterns!

You might be right. I suspect that this comes down to some trade-offs. But we shouldn’t ignore the big one: right now, many students come to hate math because they can’t get over their struggle with boring bits like this. And if they hate math, the odds of them coming to understand its deep patterns seem slim.

Q: You shared that xkcd, but did you read the roll-over text? It says that thing about languages not having words for numbers over two is a myth!

Indeed, if you hover your cursor over the text, it’ll say —

Cue letters from anthropology majors complaining that this view of numerolinguistic development perpetuates a widespread myth.

As I understand it, this goes too far: there seem to be quite a lot of cultures that don’t have words for numbers above two. In fact, English itself has some intriguing hints that it once might have lacked numbers above two.2 In any case, words for numbers over ten probably only go back about ten millennia, to the dawn of agriculture — while poems probably go back a hundred millennia, to the dawn of language.

Q: You cite “one, two, buckle my shoe”, but that only goes up to ten — and who has a problem with the numbers one to ten?

First, when my eldest daughter was four years old, I asked her what her favorite number was. She squinted and looked up, giving the question more thought than I had anticipated.

“Six”, she finally said, seriously.

“Huh!” I said. “Why six?”

She stared at me. “Well, it’s a pretty big number.”

So I’ll suggest there is a period where the numbers up to ten are actually a pretty good place to focus! But second, the original rhyme went further — at least to twenty:

One, two, buckle my shoe; Three, four, out the door; Five, six, pick up sticks; Seven, eight, lay them straight; Nine, ten, a big fat hen. Eleven, twelve, dig and delve; Thirteen, fourteen, maids a-courting; Fifteen, sixteen, maids in the kitchen; Seventeen, eighteen, maids in waiting; Nineteen, twenty, my plate’s empty.

Q: Are you suggesting we should teach kids that particular rhyme?

Sure, why not. Egan suggested we should, and we could do worse.3

But we could also do better, and pretty danged quickly with an AI like ChatGPT. (That’s how I made the dinosaur- and space-themed poems above.4)

Q: The “buckle my shoe” poem is just about counting, but your ChatGPT-enabled poems do other stuff.

Indeed — the dinosaur poem gives the sevens times table, and the space one does powers of two. I picked those because they’re things I’ve seen kids struggle with (both as an elementary-school teacher, and as a college-admissions-test tutor).

Q: What other math things might we use these for?

I’m not sure — I invite you to suggest some in the comments section! (And if you’d like to share the poems you come up with, you can do so there, too.)

Wanna suggest a hard math thing we can use poems for? Or want to share some of your own terrible math-supporting poetry? PLEASE LET US EXPLOIT YOU. Become a subscriber and join in the comments conversation.

8. Physical space

The fail state of this pattern is that we work to create counting poems and teach them to kids — and then let them become forgotten! (Now kids can feel bad about two things.) We need to make these poems shared information.

At home

Print out a poem and put it on the fridge (or close to wherever you do math).

Note that you needn’t start by memorizing these — you can start by just using them a lot. Some of the math knowledge will get learned automatically through that, and the poems can be forgotten. The few poems that continue to be useful might then be learned by heart, and it’ll be a lot easier to do so after using them a bunch.

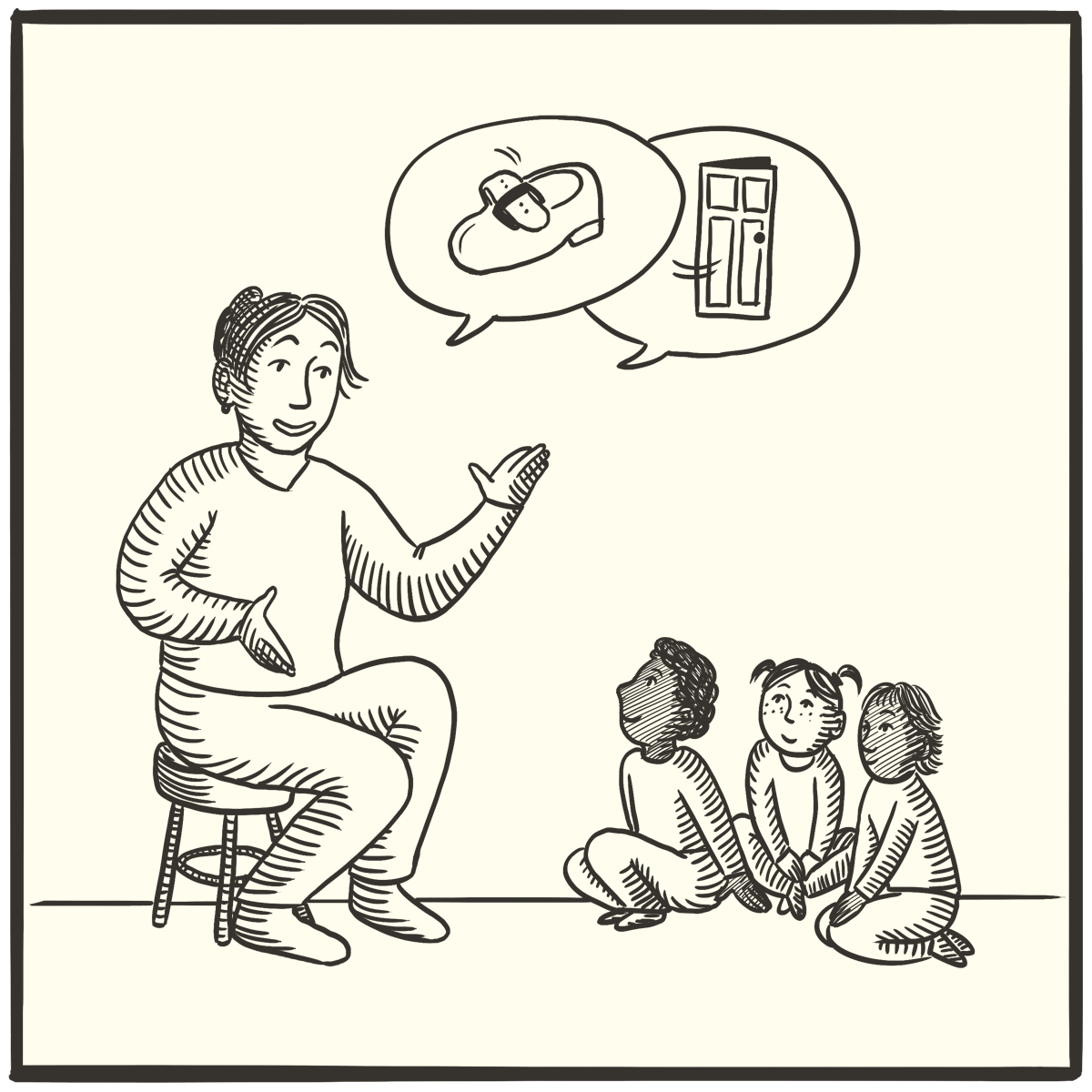

In a classroom

Make the poems poster-size, and (crucially) illustrate them — having an 🧙♂️IMAGE for each dinosaur- and space-object will make them much easier to learn.5 Let students walk up to it whenever they need to do math.

9. Who else is doing this?

The “buckle my shoe” rhyme is still taught in English-speaking kindergartens, so that’s good. And I was inspired to apply this to higher grades by classical schools, where students routinely chant their Latin conjugations and declensions.

But I don’t know of anyone who’s riding this horse as far as it’ll go.

[Edit: one reader wrote me to remind us all of Schoolhouse Rock’s “Multiplication Rock” videos. Yes, this!]

How might we start small, now?

Anyone want to improve my two (ChatGPT-assisted) poems?6 And if you end up printing these off and illustrating them, feel free to share!

(This isn’t “small”, but if anyone would like to put our heads together about making a kids book of math rhymes, feel free to reach out.)

10. Related patterns

As I wrote above, some of these poems might warrant memorization; this can be done through The Art of Memory° or by other tricks.7

Once learned, these poems would be an easy way to practice Public Speaking°.

With A Market for Lessons°, I can imagine some teacher (possibly with the help of AI) making a bunch of high-quality counting-poem posters and selling them to other teachers around the English-speaking world!

In any case, this is most like Geeky Songs°, which does something quite similar for other subjects.

Afterword:

Our rescheduled book club meets next week Saturday (May 4) for paid subscribers: 3pm Eastern Savings / 12pm Pacific Savings. We’re talking history; take a look at this link. As always, look for the Zoom link in a special post the morning of.

And we’re doing a live Q & A for our Learning in Depth Summer Intensive in two Saturdays (May 11) for everyone who signs up. It’s at the same time as the book club (3pm Eastern Savings / 12pm Pacific Savings). If you’ve signed up already, you’ll be getting something from us soon!

To be clear, we do have some innate numerical abilities: we can “subitize” (immediately tell whether there are two or three or four Skittles left on the plate), and we have an “approximate number sense” (a sense of whether you have more Skittles than me). But beyond that, we don’t have much.

Why do we say “first, second, third, fourth” instead of “one-th, two-th, third, fourth”? Something odd is going on with that set of our numbers (linguistics call these “ordinal” numbers) — the words for “third” and “fourth” and after match the normal counting numbers (“third” sounds like “three”, “eighth” sounds like “eight”, “seventeenth” sounds like “seventeen”…). I’ll admit that I’m a bit suspicious about this, though — the reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European (English’s the great-great-grandfather) has similar words for both sets.

Among other things, it introduces kids to the important life skill of shoe-buckling.

Getting a good-ish one isn’t quite as easy as “write me a poem about…”, but that’s the first step. We’ll be teaching a lot about how to get an AI to give you good poetry in our Learning in Depth Summer Intensive, by the way.

Among other things, it’ll introduce kids to the important life skill of Velociraptor-spotting.

The dinosaur poem could be improved by unifying the various actions — modifying it so there’s some sort of communal activity (a party? a samba line?) going on would make it easier to commit to memory. (Also, what does “takes her turns” mean, anyway? LAZY.) The space poem could be improved in a bunch of small ways — like the fact that the beat changes after the second stanza.

I should probably make a pattern for some of the poem-specific memory methods I use. In the meantime, I do teach ‘em in my curriculum “Eating Poems”.

As someone with a math degree, I'm not sure what "understand how sevens work" would actually mean either.

Wikipedia gives an abundance of divisibility rules for sevens, but none of them seem actually useful: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divisibility_rule.

Five hundred and twelve,

Beyond Neptune we will delve?