1. A problem

We don’t know what to do with great art.

We all sense that there’s more to experiencing at a painting than just giving it a once-over, but when we come across one in the wild (at, um, an art museum), we’re confused at what it is we’re supposed to do, exactly.

We shuffle around, we re-read the plaque, we perhaps make a comment about the use of shadows or form or whatever, and then we move on.

We worry that the problem lies in ourselves — we must not be “art people” — when the real problem is that we lack a method for going deeper.

2. Basic plan

Once a week, introduce kids to a new piece of great visual art, & use step-by-step methods to lead kids into losing themselves in it.

3. What you might see

A class paying absurdly close attention to a painting or sculpture, stating what they observe, guessing at what’s going on, and asking questions.

Kids periodically closing their eyes, trying to hold the work in their heads.

A kid mimicking the pose of a character in the painting, trying to re-create in their imagination what the character must be feeling, hearing, smelling, seeing, and thinking.

Eventually — but not right away — the teacher telling the story of how the artist came to create this piece, and how that’s connected to the larger story of how art has evolved over time.

In short: people loving art.

4. Why?

There’s power in art. An artist will labor weeks, months, or years on a single work just to reach into us in a way that words struggle to. When we let them, we add their experiences and insights to our own. We become more fully human.

Alas, this takes time — and the world is now filled with shinier and shinier things, shallow objects and apps and activities that capture our attention, yet deliver less of the experience we ultimately want.

We so rarely take the time to open ourselves up to the visual arts that when we visit an art museum, we find we’ve forgotten how.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

This wasn’t always so. Back in the Bad Old Days — before the shiny-ness revolutions — our ancestors could hope to experience a great piece of art only rarely, perhaps at a temple, cathedral, or Great Mosque. To our ancestors, an oil painting was a 8K, Ultra-High Definition, High Dynamic Range, bezel-less display — to stare at it in wonder and reverence was expected. It was normal to hope that they would have an encounter with the piece that would change them.

Our modern relationship with fine art grew out of this.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

The trick for connecting with visual art is to use as many of Egan’s tools as cleverly as possible.

We want to tap into the mind’s innate 🤸♀️FASCINATION WITH PEOPLE to help kids experience any characters in the art as friends. To do this, we might encourage them to 🤸♀️MIMIC the poses of those characters and physically imagine the 🤸♀️SENSES they’re experiencing. (What’s up with these weird emoji, you ask?)

But we also want to lean on language. 🧙♂️MAKING A LIST of what we observe can take us a long way; when it’s relevant, we also want to try our hand at telling the 🧙♂️STORY of what’s going on in the picture.

Learning the origin story of the piece — how it relates to the artist’s life — provides 🦹♂️HUMANIZING KNOWLEDGE, and perhaps helps us 🦹♂️ASSOCIATE WITH THE HEROIC. And seeing how the piece exemplifies some trends in the history of art helps us see👩🔬PROCESSES RATHER THAN HIGHLIGHTS.

And truthfully, there are few better ways to learn about the history of ideas than by understanding the stories of 19th and 20th century artistic movements. In the history of art, you can see 👩🔬THE SEARCH FOR AUTHORITY AND TRUTH (and especially the search for a true 👩🔬DEFINITION OF SELF) played, and played out — culminating in the postmodernist 😏APPRECIATION OF AMBIGUITY.

But at the end, all of this spirals back to build SOMATIC (🤸♀️) understanding: what we hope to get from visual art is exactly those experiences that don’t fit inside words.

6. This might be especially useful for…

Artsy kids, duh.

7. Critical questions

Q: Excuse me! I have a snarky question for you!

Great — but shut up for a minute; I want to skip ahead to the next two sections.

Q: But, but —

Onward!

8. Classroom setup

Since purchasing original pieces of professional art trends a tad pricey, we’ll want to either print out images of these pieces (on a nice color printer), or display them on a quality monitor (or, for a classroom, a projector).

In either case, to heighten the specialness of the art, we may want to dim the lights in the rest of the room.

I.I.: What should we do with the pieces of art afterwards?

I say, hang them up all around the room. This is a wonderful way for kids to feel that the classroom is a friendly space — look, they have near-literal friends all around it!1

Even more helpfully: this keeps all the art “in play” throughout the year. Kids can refer back to a certain piece to compare it to a new piece, or when studying literature, or whenever.

I.I.: Gah, so visually BUSY.

To unify them, you can put each in a black picture frame. (When you’re printing them out, the size of this can be useful to note.) Frames can be expensive,2 and if you can’t find a deal on them, painting some Goodwill frames black (or even just having your kid make some out of poster board) is a clever solution.

9. Who else is doing this?

It really feels like every educational reformer talks a big game of art appreciation, but when you scratch the surface of Montessori, Steiner, Dewey, or the Reggio Emilia folks, their advice usually comes down to “encourage students to have personal experiences with art.”

Thanks, educational reformers. (Am I wrong about this? I bet I’m wrong about this. Someone tell me I’m wrong about this — I’ll give you a week’s gift paid subscription so you can comment.)

I’ve come across three exceptions — programs which provide actual step-by-step methods of engaging art.

A: Visual Thinking Strategies

Take a piece of art, and…

Ask, “what’s going on here?”

Ask, “what do I see that makes me think that?”

Repeat step #1

The virtue of this method is its simplicity — which allows it to be useful for any piece of art, as well as other things, like an aquarium, or a plate of food. More about this method can be found at the Visual Thinking Strategies website.

B: Charlotte Mason’s “Picture Study”

Select: choose an artist and six of their artworks

Introduce: tell a bit about the artist, focusing on interesting aspects of their life

First look: present one work, and stare at it silently for a few minutes

Narrate: take away the image, and ask the child to describe the work from memory

Discussion: talk about what you missed, exploring details

Go deeper: tell them more about the artist and the style

I’m an increasing fan of the Charlotte Mason approach to education — if you haven’t heard of this community, they might be the most Egan-adjacent boots-ready option in homeschooling.

Besides its simplicity, a virtue of this method is that it’s made for long-term educational engagement. (Here’s a short YouTube video walking through how it can be done.)

Years ago, I led a small art appreciation class with homeschool teens in Seattle. I found both of these approaches helpful, and borrowed some of their techniques, but this final method took the cake, and has led to some of the most aesthetically exciting experiences of the last decade of my life:

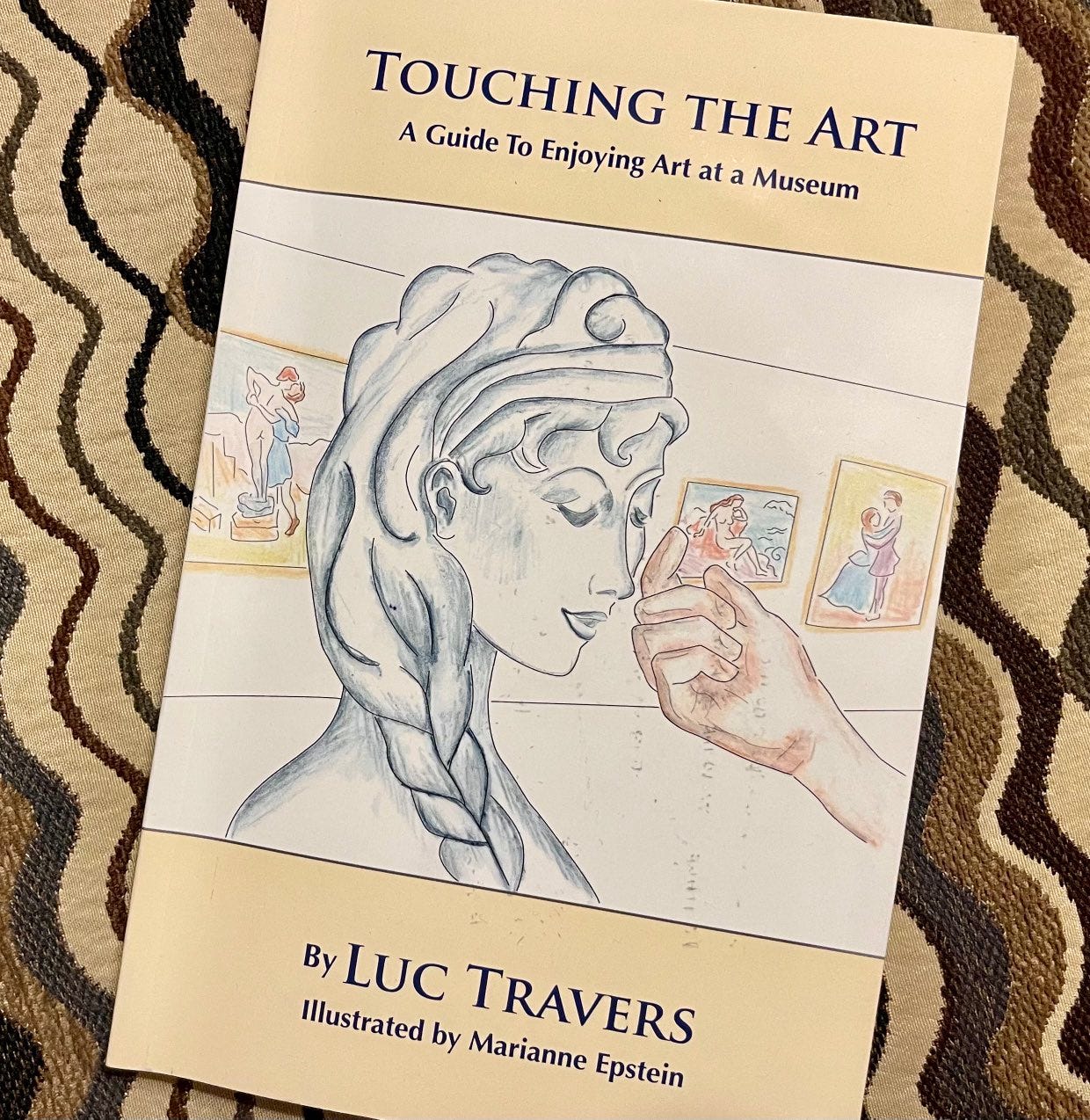

C: “Touching the Art”

His method draws upon most of Egan’s tools that I’ve listed above (and to my knowledge, Travers hasn’t heard of Egan).3 It’s complex enough that I won’t enumerate its steps here, except to say that —

a disproportionate number of the examples above come from it,

there’s still more, and

if anything in this pattern excites you, you’ll devour the book.

Travers also has other resources available on his site, touchingtheart.com.

How might we start doing this small, now?

Next Saturday — March 2, 2024 — we’ll try these methods out in our monthly-ish book club! See below for details.

(If you live in the far distant future, where “March 2, 2024” is only something you talked about briefly in history class, and also your history teacher was a cyborg for some reason, then I might recommend just go to the Random Classic Art Gallery, and trying these methods out!)

Section 7, take two: Critical Questions

Q: What do you mean “great art”? Who’s to say what’s “great”, you fascist imperialist neo-colonialist PIG?

Here, I just mean “great art” to mean “professional art that we think worth a student’s time” — which is to differentiate it from the art that kids are creating themselves in class. (Though what art is great is a great philosophical question that we should engage kids in, too. And yes, politics may come into that — I’ll just leave them off of here.)

Q: So are we ready to tackle all styles of paintings?

Kinda. As I said above, the Charlotte Mason “Picture Study” approach can be used on almost anything, and the Visual Thinking Strategies (cool kids call it “VTS”, but I’m not that cool) approach can be used on anything anything. The power of “Touching the Art” is that it helps us unearth the story elements in artwork — which restricts its scope to artwork with human (or human-ish) subjects.

Frankly, I’d love some other methods that utilize Egan’s tools to press the meaning button in kids minds as they engage artwork. If you’re reading this, and you have an idea, let me know!

Q: What order should these be in?

Part of me wants to say “no order at all, pure chaos, ha ha ha!”… but that probably culminates with everyone staring at Edvard Munch’s The Scream for a twelfth of their childhood — or not at all. (This is the same fail-state we talked about overcoming in Cumulative Content°.)

Another part of me wants to say “connect this to the scope and sequence of the history curriculum” (look forward to Spiral History° on April 5). That has the advantage of helping us literally see and feel the cultures we’re talking about. (It’d also help nudge us out of our own culture’s art.) The fail state here, though, is that there’s been so much of a profusion of art and artistic styles in just the last century.

So… maybe it’d be nice to compromise between the two? Weeks could switch back and forth between something that helps us connect to history, and just a really fun piece of art.

Which is all to say: I don’t know, and I’d love your thoughts.

10. Related patterns

This has a few sister-patterns: A Song a Week° and A Poem a Week° (July 3), which both share its cadence, and A Movie a Month°, which doesn’t.

It draws upon the ineffable experiences that are also cultivated by Strange Sensations° and Capturing Experience with a Marker° (April 12).

Of course, it’s a piece of a larger art curriculum that, yes, also involves making art! Look forward to Simple Doodles°, Drawing in 3D°, Drawing What You See° (July 19), and more.

But after talking to my friend Sam about this, I realize there should be other patterns for art appreciation, too — like Aesthetics, Unpacked° to handle things like color theory and Understanding Comics° to engage things like how lines and forms affect us. That conversation also made me realize that How to Take Photos° is a more relevant skill now than ever before.

Afterword: Going full-meta, here

Aforementioned book club next Saturday! And, what the heck, we’ll try out some of these methods together!

Saturday, March 2, 2024

3pm Eastern / 12pm Pacific

I’ll make a separate post about this. As usual, it’s for paid subscribers only. I’ll strongly suggest that you purchase Touching the Art (the e-book is just ten bucks, and it’s short and beautifully written) beforehand, but we’ll also be trying out the other methods, and will be wrangling with the strengths and weaknesses of each.

And, of course, talking about what role art appreciation can play in a new kind of school.

And maybe some other stuff. Let’s find out. (The link will be going out later this week.)

Probably if you’re homeschooling this isn’t as helpful — unless your living room doesn’t already feel friendly? In which case, sure, go at it.

Like 3-ring binders, this feels like one of those corners of the economy that’s gotta be run by a cartel. How could a simple wooden photo frame really cost $15?

This is another of those confirmations to me that Egan was onto something — you see his tools reinvented by people who’ve never heard of him who write the coolest books.

I was going to make sure to mention Charlotte Mason's picture study if you didn't! It's good for grown-ups to. The moms in my Charlotte Mason group did one where we went up in twos to the hosting mom's home office to look at an image and then came downstairs to try to draw what we remembered. It felt like something we undertook in awe because of ascending and descending in silence (mostly due to the office being small!) and it gave us something different to do with drawing than "try to be good at it."

In high school, my AP Euro teacher had us all come *back* to the building the night before the AP exam and took us on an art walk around the school, highlighting works that touched on the history we'd learned. (There were a lot of framed prints in the hallways, but we mostly hustled past them). It was a review, but a review that (like the picture study) was touched by awe and clearly pointed *beyond* the test we were to take.

No snarky comments this week!

I find the idea both intoxicating and timely, as I plan to start “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain.” Super-excited to do this for book club — just bought the PDF…