1. A problem

Egan education claims to launch kids on an actual intellectual adventure — but in a real adventure, the hero must descend to the underworld.

2. Basic plan

Starting in middle school (grade 5), students identify one fear each year.1 At the start of the second semester, classes brainstorm together what their fears might be, and brainstorm how they might be lessened. Students — in pairs, or on their own — embark on small experiments to see if they can reduce their fear.

3. What you might see

You might see teachers presenting on the psychology of fear — its evolutionary wisdom, its neurology, its cultural aspects — and students rapt, hoping to hear something they can use to combat their own terrors.

Beyond that: students supporting each other as they try scary things. Students keeping data that they actually care about.

And, of course, presentations at the end of the year about how it went.

4. Why?

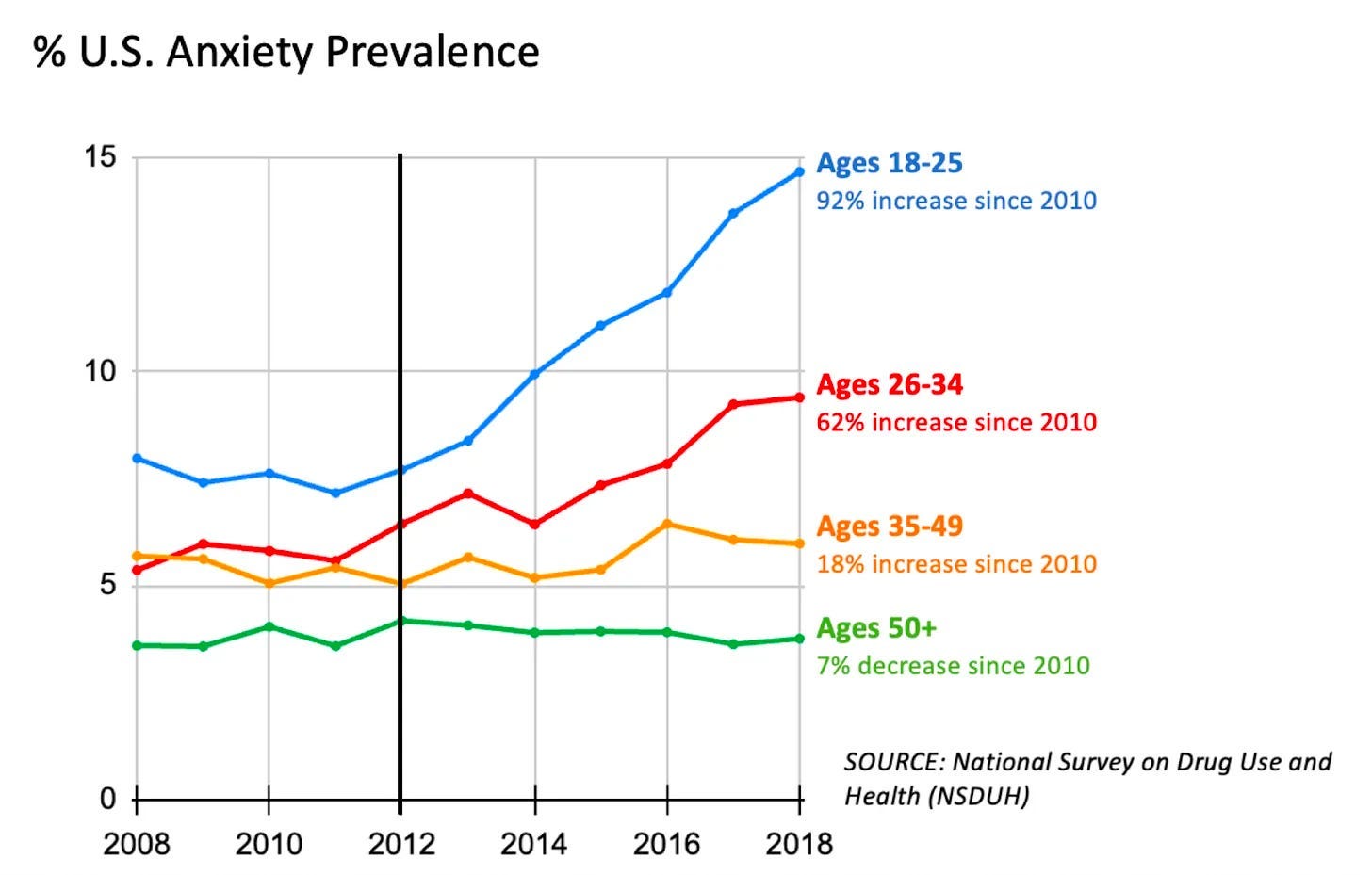

We’re living through a period in which anxiety is rising, especially among the young. This seems to follow in tandem with a sense that the world is a dangerous place, even as in many ways it’s been becoming less dangerous.2

In any case, our emotions shouldn’t be glued to what’s happening in the world. To a wonderful degree, we can shape how we feel — and perhaps never more than with fear. There are oodles of techniques that really work to lessen our fears.

This is all to say: schools can show kids how to become stronger.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Facing fear is replete through anthropological literature. Facing your fears is in many groups a major part of coming-of-age rituals: it’s a requirement for being an adult.

In fact, one of the only places where it’s missing is our culture. (Have you worn a mitten full of bullet ants? If not, you might be WEIRD.)

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

Not to put too fine a point on it, this involves some pretty strong 🤸♀️EMOTIONS — not just fear, but also bravery, and the hope of not fearing that thing anymore. It’s a straight-up literal way of 🦹♂️ASSOCIATING WITH THE HEROIC.

(What’s with the weird emoji?)

Taking this on as a series of trials is a great way to help kids see the power of 👩🔬HYPOTHESIS AND EXPERIMENT. Guiding them to see their reactions as processes in the world (in the mind, in the brain) lifts them to a sense of objective reality that changes their 👩🔬DEFINITION OF SELF.

6. This might be especially useful for…

Scaredy cats, natch! Lots of kids are overcome with irrational fears — heck, lots of adults are, too.3 But being scared of things like this isn’t an immutable fact about ourselves.

This also seems useful for kids who have a burning desire to accomplish impressive things in the world. Eventually, they’re going to hit fears: we can show them how to dismantle them.

7. How could this go wrong?

We make a fear worse

This seems like a real danger. I suspect we can’t get rid of it, but that we can lessen its effects by talking about this ahead of time, and letting kids opt-out at any time.

Students mock each other’s fears

If there isn’t enough trust in a classroom, this seems likely. This is part of why I think it’s best to wait until the second half of each year to do this. We should also treat this activity as a special (dare I say sacred?) process, and design in consequences for students who do this (and be open with them about this).

That all said — some mockery is inevitable. (Because, y’know, they’re middle schoolers.4) We shouldn’t let that torpedo this pattern. In fact, sharing fears (and working through them) is a massive opportunity for group cohesion.

…and probably “being mocked” is one of the fears that we should encourage students to work on.

Can you think of another way this could go wrong… or, um, a way to help avoid that? Become a paid subscriber and join in the comments conversation!

8. Classroom setup

—

9. Similar stuff (others are doing)

I think I was inspired by Jia Jiang’s hilarious and powerful book Rejection Proof, which I read with a Toastmasters group, trying to transcend our lingering stage fright. (I recommend his TED talk to start thinking about this.)

10. Open questions

Is anyone else as excited as I am about this?

I mean, I don’t know, whenever I think about this idea, it sounds incredible — like one of the greatest things we could ever help people learn. It’s the sort of thing that, in theory, any of us could take on ourselves, but it’s SCARY, and so we don’t. But I suspect it’s the sort of thing that a group can do much more easily.

Does anyone dislike this idea?

11. How could this be done small, now?

Let’s get concrete. First, what fears did we have, when we were in middle and high school? (Hint: they’re probably the same fears we have now.)

Second, let’s take “afraid of the dark” as an example. How might we imagine a kid addressing this? What ideas might they mull over? What experiments might they try?

See you in the comments section…

12. Related patterns

(See the whole index o’ patterns.)

Probably this “we conquer fears, here” attitude should be reflected in our Named Virtues°. This contributes Every School a Tribe° — the sense of group identity and real community that every school can have.

As public speaking consistently ranks near the top of people’s fears, this dovetails nicely with Kids on Stages°.

And we might get ideas for fear-facing when they delve into the annals of anthropology with Customs & Cultures°.

“But when I was a kid, middle school started in 6th grade!” Yeah, local customs differ. I’m going to adopt the term “middle school” for 5th–8th grade, because it breaks up the curriculum into three loops of four years each. (Please don’t misinterpreted me as having an opinion on the age-old belief of when we start sending kids to different campuses; there are interesting things we could be talking about.)

This is notoriously difficult to measure, by the way — I no longer blithely say things like “the world is safer than ever before!”

I’m still afraid of the dark.

And high schoolers, who in my personal experience are marginally less rotten.

Funny story: When we were kids one of my siblings started a "brave club." The club only had 2 members... said sibling who served as president, and our youngest sibling who served as, well, the rest of the club membership. My sibling who served as president wanted to do brave things, but I guess needed a reason to do them, so the purpose of the club was to provide a forum where she was tasked/assigned (by the youngest sibling) to attempt feats or bravery. The only one I remember is walking along the top of the wall that ran along one side of our yard. My sibling probably would have loved this sort of an assignment.

In a big picture sense, I love the idea of a classroom community where a wide range of student personalities/abilities/etc could feel so safe that they could take on something like this. I would love it if every student felt this seen and supported in their learning environment. But I have to say my scope of practice radar is going off over here. For some students (I'm specifically thinking of a number of neurodivergent students who I know very well) I have some concerns that without good guardrails in place type of assignment could easily creep out of the scope of practice for teachers. So you would need to have some very clear guardrails and training for what kind of guiding questions teachers could/should use, etc. and how to facilitate this process. (As an aside and for context, I am certified in Equine Facilitated Learning and one of the things that was drilled into us in our training was that we are NOT Equine Facilitated Psychotherapy certified and that therefore there's a level of processing/questions/etc and line in the sand that we SHOULD NOT cross because t we are simply not trained or qualified to enter that psychological territory with a client and could do damage/cause trauma as a result. I would apply the same logic here to teachers.)

The inverse "How this might go wrong."

Kids will only share "socially acceptable" fears that they hope won't trigger their peers or teachers.

Thus, we end up with psychology theater that makes teachers feel like they are solving the problem,

but actually teaches kids to totally distrust anyone who claims they want to help,

and bury their actual fears even deeper inside.

[Why yes, I am still slightly bitter about religion, thanks for asking]