1. A problem

After thirteen years of schooling, if we drive out on a country road on a clear night and stare up at the sky, most of us can only say, “Those are stars. They’re very far away.”

2. Basic plan

Starting in kindergarten, teach the juicy bits of traditional star lore — the most easily-spottable constellations, the revolving signs of the Zodiac that progress throughout the year, and the stories that traditional cultures (starting with the Greeks, and going beyond) told of what these things meant.

Starting in upper elementary school, add on our modern star lore — the things that science teaches us about what these star-things really are.1

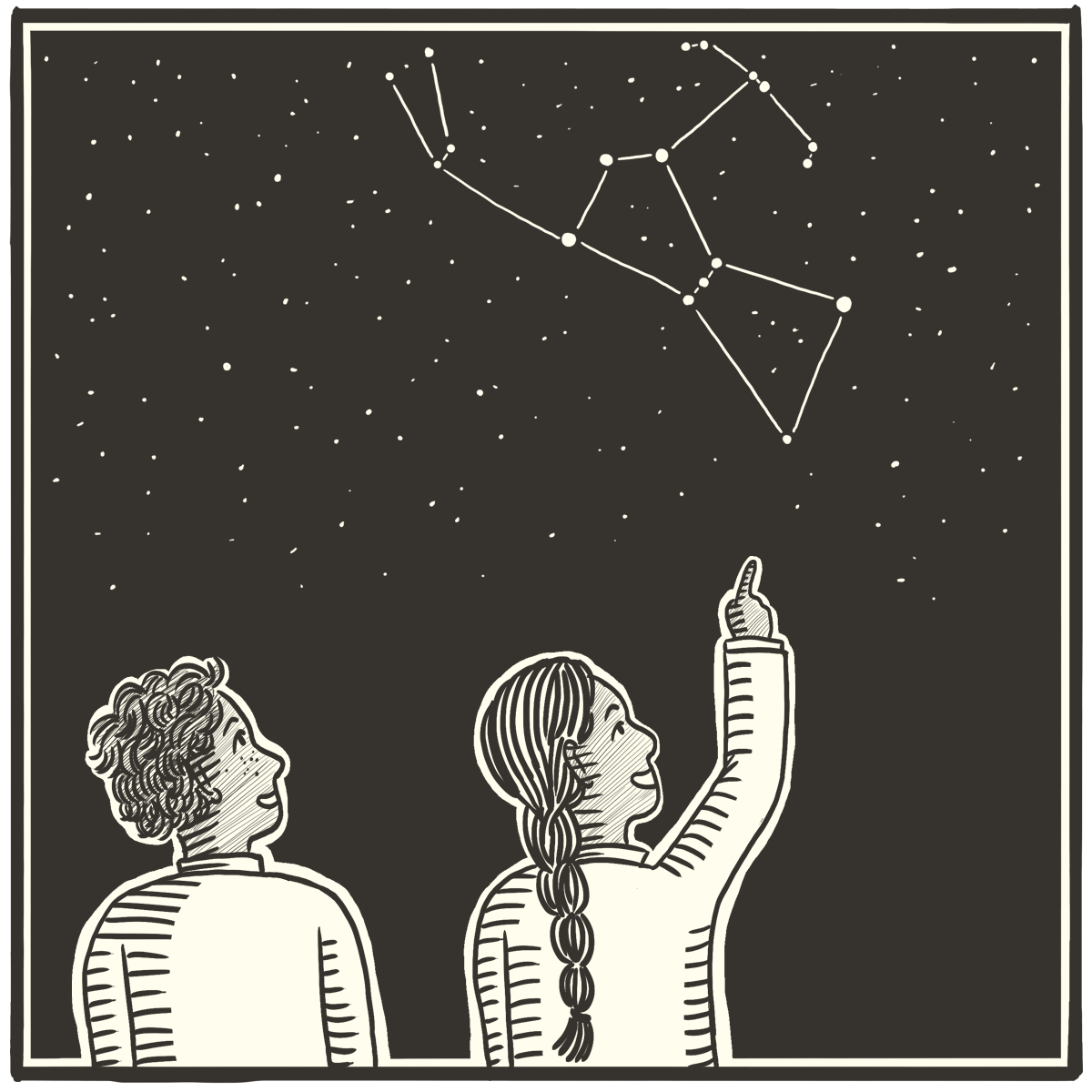

3. What you might see

Kids first learning stories, and later learning to see the night sky in 3D.

4. Why?

The other stars are suns, too — the reality that we can see at night is vaster than we can really fit into anyone’s head. This isn’t just another fact that science has discovered: it launched a revolution in how we make meaning of the Universe and our place in it. (It probably wasn’t for nothing that the authorities burned alive the first person to say it.)

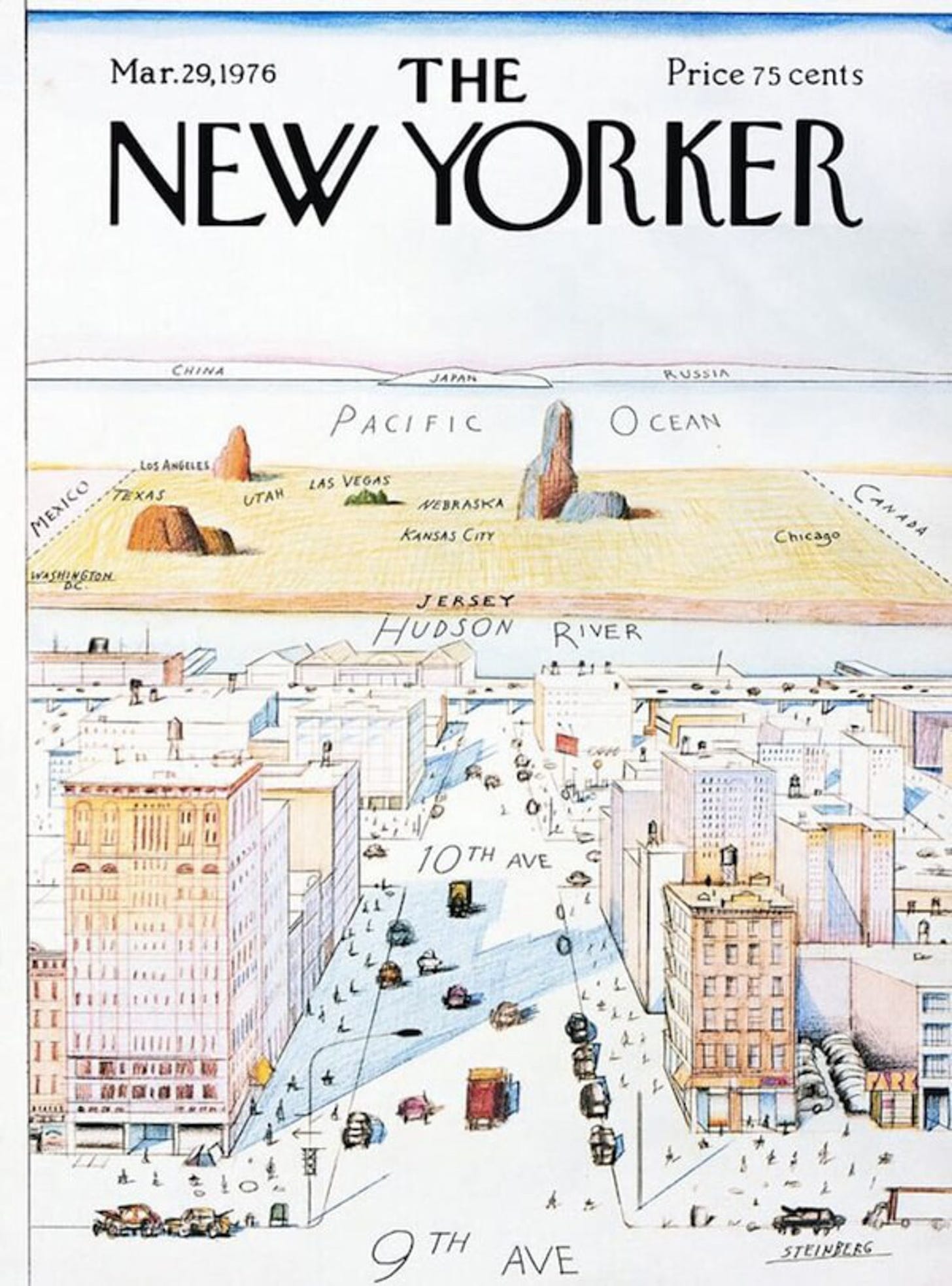

And yet when we look at the stars, we naturally imagine them as in the same place — “out there in space”. Let’s all say it together: space is not a “place”. When we look at a star chart, we don’t recoil that it’s more self-centered than even the famous New Yorker cover mocking how New Yorkers imagine the rest of America —

This is all to say, we don’t actually see the Universe according to what we know is true. We fall back on seeing it in the same way the ancients did — relatively small, with us in the center.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Every single culture sees specific humans, animals, and events in the stars. People in these cultures know the stars intimately, and use them to make sense of the time of year and time of night.

This intimate knowledge of constellations cultivated enough interest to launch astronomy.

In other words, it’s the old Egan idea: story precedes science.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

We tell the MYTHIC 🧙♂️STORIES behind these things, first from the Greeks, and later from other cultures. While we’re re-telling them, we should them illustrations of the constellations we’re talking about to help kids form 🧙♂️VIVID MENTAL IMAGES. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

And then, when they’re ready (and the weather is right), we take them outside at night! For homeschoolers, this is easy — for people running schools, this is a lot of paperwork. And yet, it’s absolutely worth it: an outdoor nighttime experience is inherently exciting. The darkness is scary and cold, and to be in a new place with your friends is unforgettable. That’s to say that this taps into any number of SOMATIC (🤸♀️) experiences.

As we begin to layer in the findings of contemporary science, we should take advantage of the oodles of 🦹♂️WONDER and 🦹♂️AWE that come with astronomy. (This is a great time to show the TV show Cosmos, both in its original version with Carl Sagan, and in its new iteration with Neil DeGrasse Tyson.)

All of this lays the groundwork for a clear-eyed understanding of one’s self as not being the center of Universe, but as another creature: in Egan’s words, to move 👩🔬FROM TRANSCENDENT PLAYER TO HISTORICAL AGENT.

6. This might be especially useful for…

Kids for whom learning about people comes more powerfully than learning about things. And, of course, the opposite: Aspie sci-fi loving space nerds!

(Does this feel like cheating? Very well, this feels like cheating.)

7. Critical questions

Q: Which stories?

Stories like the one of King Cepheus — weird tales that connect the dots between the stars.

Q: You’ll forgive me for forgetting that one?

Probably just no one told it to you — it’s fairly unforgettable! Cepheus is the African king who boasts that his wife Cassiopeia is so beautiful that she puts the sea-nymphs to shame.2

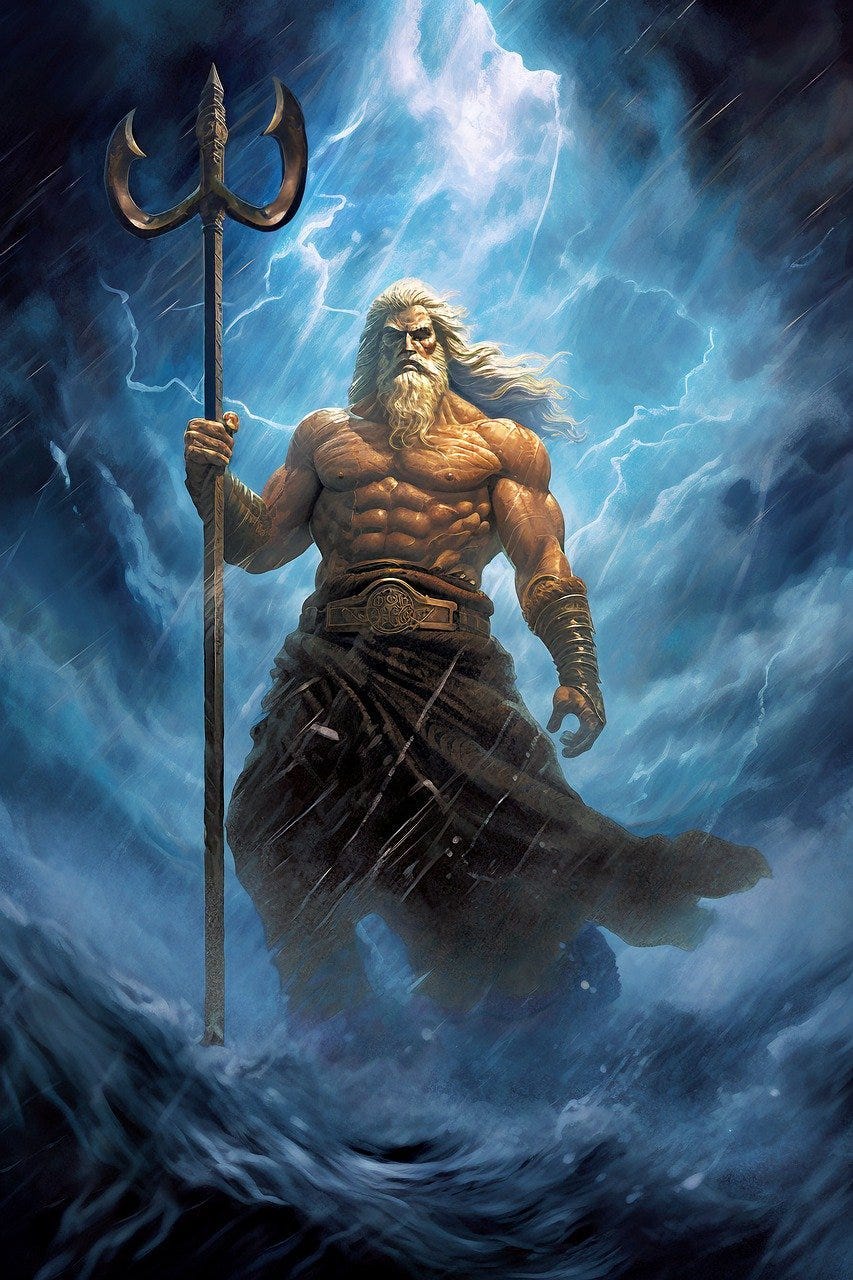

This cheeses off the sea god Poseidon, who chooses to put Cepheus in his place by sending a voracious whale to destroy any ships that come to the harbor, plunging the populace into poverty.

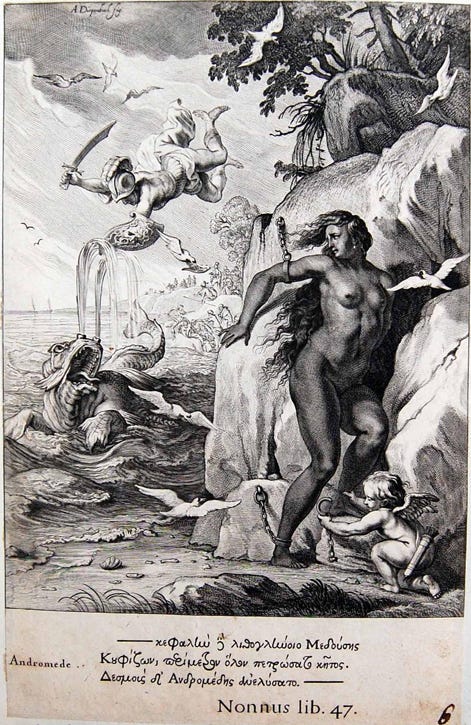

To save his kingdom, Cepheus listens to the advice of an oracle and decides to sacrifice his daughter (the Princess Andromeda) to the whale’s hunger.

As Cetus is swimming toward the rocks on which the princess is chained, the great hero Perseus, on his trip back from slaying Medusa, sees Andromeda, falls in love, and un-bags the head of Medusa.

The whale becomes a shock of stone, and Andromeda and Perseus marry, living happily ever after.3

I.I.: I thought we were talking about stars?

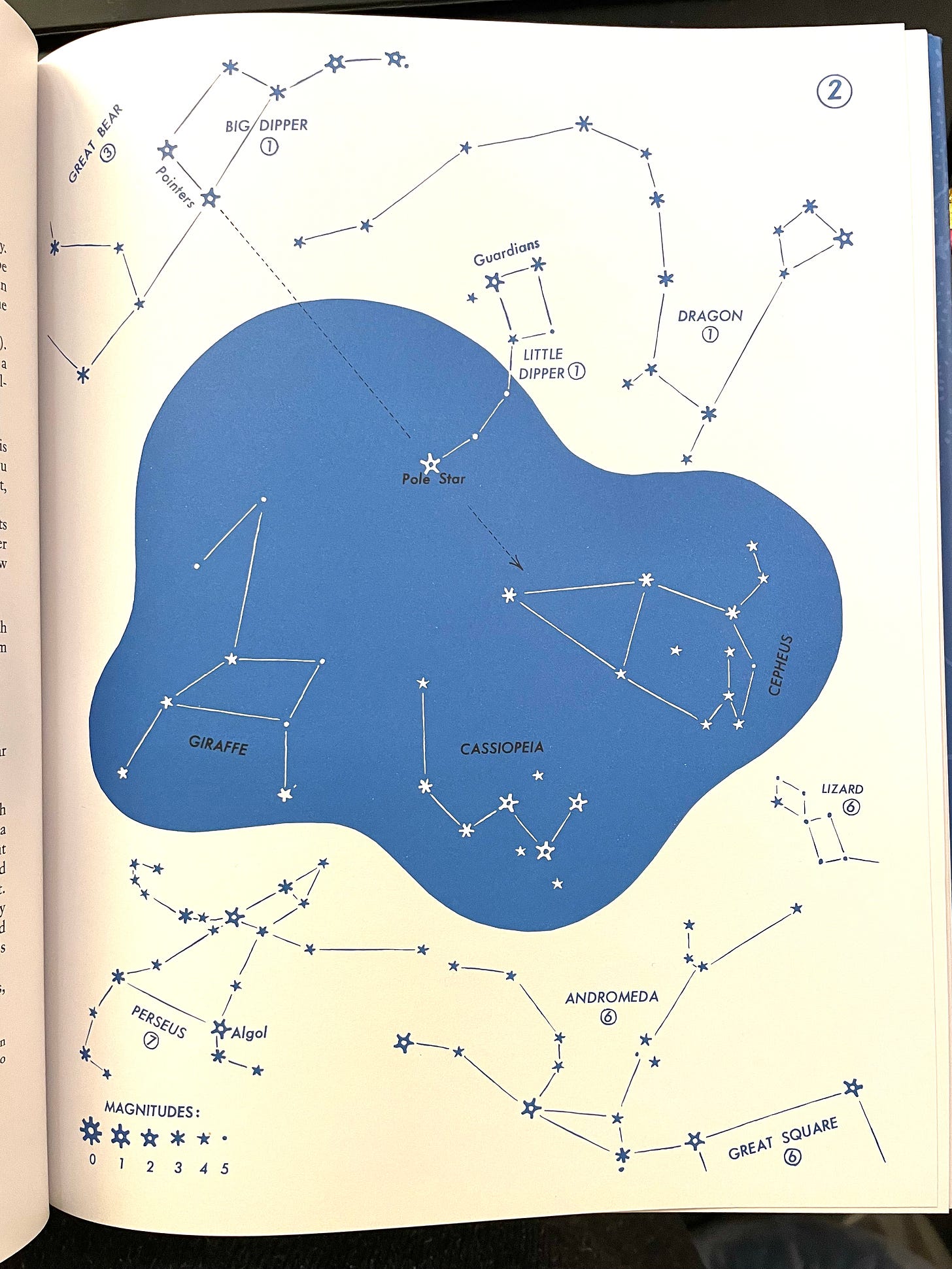

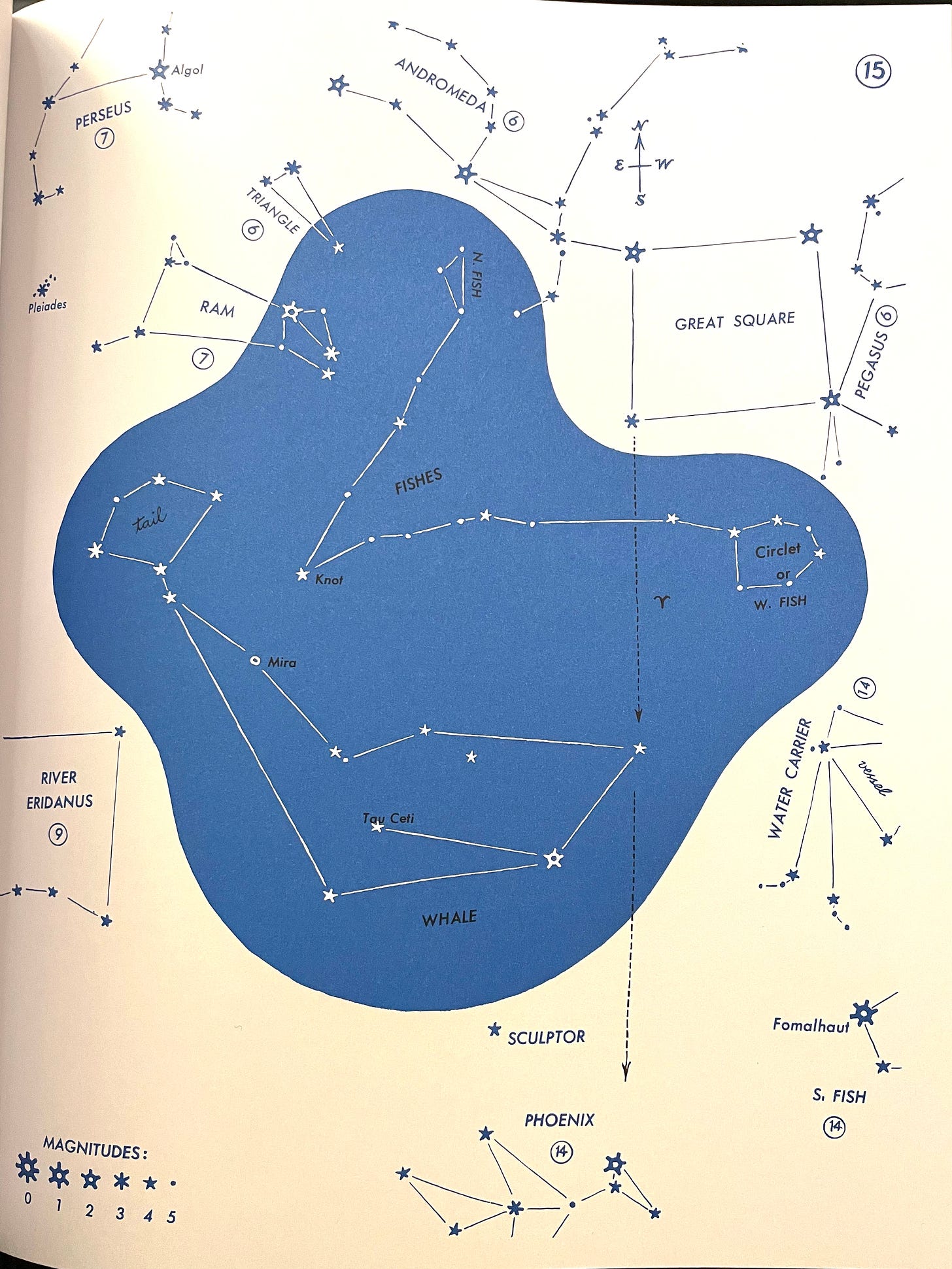

Cepheus, Cassiopeia, Cetus (the whale), Andromeda, Perseus, and Medusa are all constellations! They can be seen from the northern hemisphere from September through January.

I.I.: How about the 3D viewing?

The stars is are all so far away, there’s no parallax we can see with our eyes — the closer ones don’t shift around much compared to the back ones. Because of that, our brains perceive them as shiny dots on a black shell — indeed, until Copernicus and Galileo, even the cleverest people in the world assumed that’s what they were!

But we can learn to see in 3D. We can start with understanding what we’re seeing when we see the Milky Way — not a splash of spilled milk4 on a black surface, but the rest of a thin tortilla that our solar system is baked inside of. Then we can learn where specific stars — like the ones of Orion — are on a map of the galaxy. (Hint: Betelgeuse and Bellatrix, the stars of Orion’s shoulder, are much much closer than the stars of his belt.)

And then we can see outside our galaxy. For millennia, people noticed a bit of fuzz above Andromeda’s knee. Turns out that when you point a telescope at it, you see this:

We can even learn to spot things that we can’t see — like the black hole hidden in the swan constellation Cygnus.

Can you think of another way this could go terribly, terribly wrong? Frankly, WE WOULD LIKE TO KNOW ABOUT IT. Become a paid subscriber and join in the comments conversation.

8. Classroom setup

Nothing special — though maybe a school might want to invest a thousand bucks in a really nice telescope. The stars are still just shiny circles, but there’s something magical about seeing actual nebula and such with your own eyes.

9. Who else is doing this?

Occasionally you’ll find a high school that has a planetarium (one in our town does, how have I not visited it yet?),5 but this pattern suggests beginning this when kids are young, and listening to stories and memorizing shapes feels normal.

How can we start small now?

How can I say this politely? Most books about constellations are worse than the canine fecal matter you step into on your way to the mailbox.

And they’re terrible in a particular way that was first pointed out at least seventy years ago. H. A. Rey — yes, the guy who wrote Curious George — wrote the book The Stars: A New Way to See Them, and called my attention to problem.

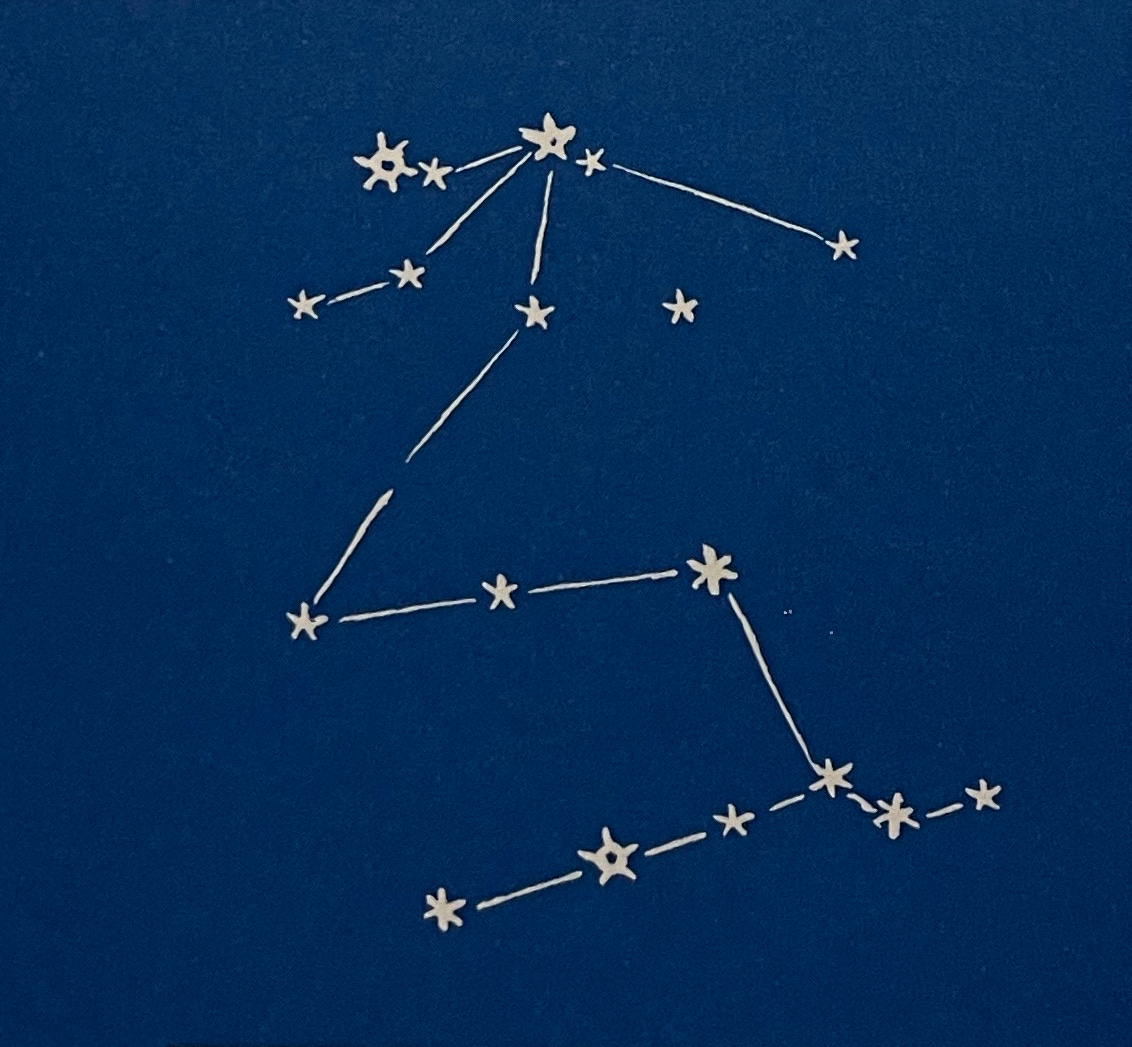

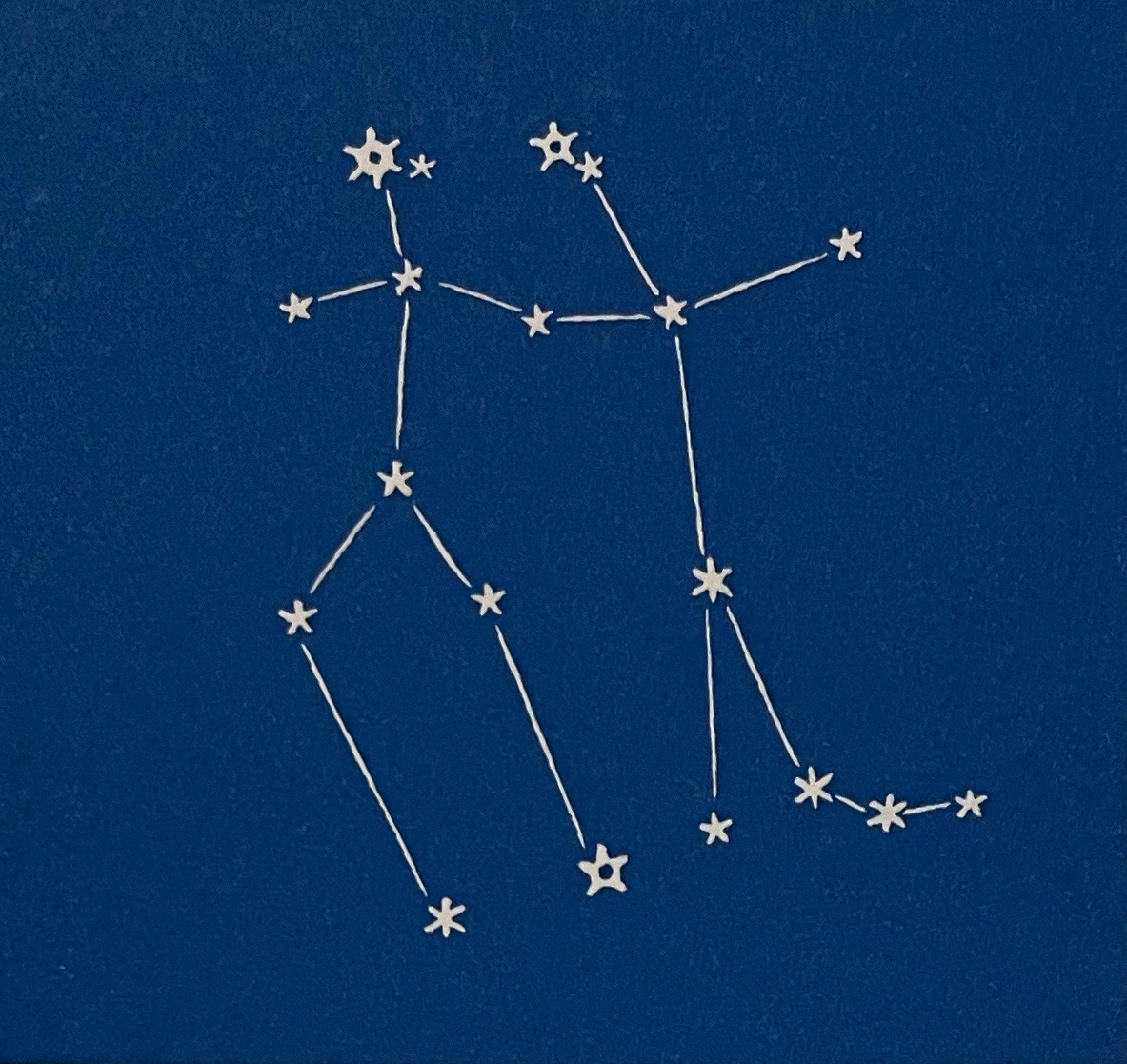

A picture’s worth a thousand words, so here’s the stars in the constellation known in the West as “Gemini” — Greek for “the twins”:

Every book on constellations feels some obligation to help you see the shapes in there. Most will do it by drawing over the stars:

But that in no way trains you to spot the constellation. In fact, in order to see the stars, you have to mentally edit out the twins! So other books on constellations will pursue the opposite approach, and show you something like this:

It might not have escaped the attention of the careful reader that now it looks NOTHING AT ALL LIKE TWINS AT ALL AT ALL. This an anti-mnemonic.

H. A. Rey, in his charming 1950s style, connects the constellations like this:

This isn’t the best way to learn the constellations, it’s the only way. (This is a hill I suspect we should all be prepared to die on.)

10. Related patterns

This is quite similar to Track the Sky°, except it doesn’t focus on the Sun, the Moon, the planets, or their motion.

Being able to pick out various constellations — first five, then ten, then twenty — could be one of the Stinkin’ Badges° kids can opt into earning.

Students’ ability to truly imagine the three-dimensionality of the Universe will be massively improved when they become Masters of Measurement° (September 4), and use that skill to Imagine the Truth is True° (June 21).

And it’s not a pattern, exactly, but a few months back I wrote up some of a lesson I gave in Science is WEIRD, to give a taste of what Egan can do to the science curriculum.

Like — fun fact — they’re not even as far away as we say!

There’s a story that the African king Cepheus is none other than the Egyptian pharaoh Khufu — he of pyramid-building fame. I like this story.

I mean, upon returning to his home in Argos he inadvertently kills his father, but that had been foretold by a prophecy, so you shouldn’t look so surprised.

Hera’s. Hercules bit too hard. (No, I am not making this up — THAT’S WHY WE CALL IT THE MILKY WAY.)

Oh, right, covid.

Keen for any other vetted book recommendations people may have related to this pattern. Have obviously noted down The Stars, but any that focus more on the constellation stories themselves are appreciated. Seems Star Tales by Ridpath could be an option?

Don't underrate the big inflatable portable planetariums! I can't be the only one who instantly got a sense of awe that I could carry over to, um, the real sky, from the fact that there was a huge, slightly squishy dome in the auditorium, and we had to crawl in the dark through a narrow, crooked passageway to be admitted to the glory of the stars! (A lot of mostly-unintentional birth imagery!)