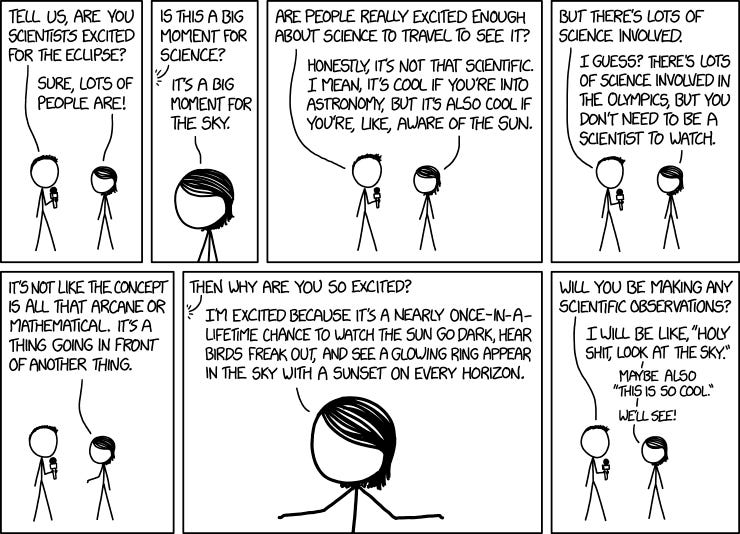

Seven years ago, right before the last total solar eclipse to pass through North America, the web comic xkcd got something terribly, terribly wrong about solar eclipses — and about science, too. Can you catch it?

As my fingers type this I feel a bit of horror, because

xkcd is the closest thing to sacred scripture that we science communicators have, and

I’m desperately, madly, unhealthily in love with it.1

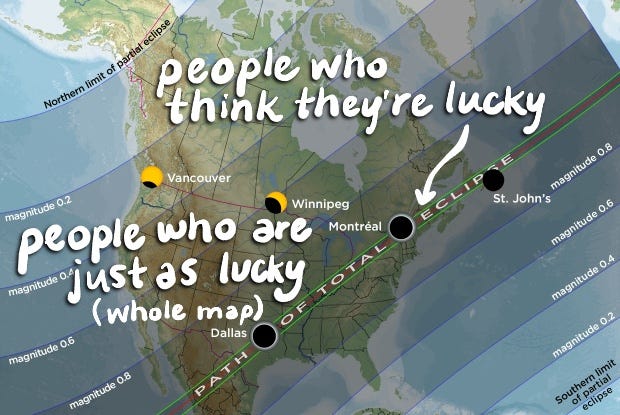

But I woke up last night at 3 o’clock with the realization that there’s something wrong baked into the above strip — one of my favorite! — and the more I thought about it, the more I understood that the error is standing in the way of hundreds of millions of people — literally everyone in North America2 — having a mind-flipping experience of astronomy.

But obviously there’s a lot this gets right! Scientists are human beings. They’re not just driven by number-crunching and paradigm-proving; they like to go wheeee like the rest of us.

It just that, um, it gets wrong what “science” actually is.

The tl;dr —

Two of the most important scientific discoveries EVER are baked into every solar eclipse, and hardly anyone realizes it, and they miss the MOST AMAZING THING ABOUT AN ECLIPSE.

Science isn’t just “the cutting-edge stuff being done by PhD’s right now” (which seems to be the definition of “science” that the interviewee is assuming in the strip). Science is so much bigger: a two-and-a-half-millennia-long tradition of trying to correct our naive way of looking at the world — a way that we still haven’t rid ourselves of. And when you understand what science is, you can have the stomach-lurching experiencing of seeing what an eclipse really is — even if you’re very far from the path of totality.

There are two wildly unintuitive scientific discoveries that you have to understand if you want to really see an eclipse for what it is.

Discovery #1: the Sun is BIG

Everyone thinks they know this, but they really don’t.

Imaginary Interlocutor: No, actually, I think I know this.

Not if you’re doing your thinking with language.

Human language deals with size by splitting the world in two. Things that are smaller than us get labeled “small”; things that are bigger than us get labeled “big”.3 On one side you have your pebbles and strawberry seeds and silicon atoms; on the other, mountains and mammoths and sand worms.

The trouble is that these things are, size-wise, more unlike each other than they are to us. To say the Moon and Sun are both “big” — the same word we apply to an aircraft carrier and the Golden Gate Bridge — is to fundamentally misunderstand their size.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Okay, the Sun is “REALLY big”. Are you happy now?

No, you’re still not seeing what’s really there. The half of the Moon that we always see is more than seven million square miles — about the area of the U.S. and Canada combined. Next time you see a full moon,4 imagine seeing North America plastered on it, with Mexico and Central America just barely wrapping around to the far side.

That’s “very big”. That’s the Moon. You’ll never see any single object in your entire life as big as the Moon… except the Sun.

I.I.: Fine, fine, it’s the MOON that’s “really big”, and the Sun is “really REALLY big”.

Tacking on superlatives doesn’t achieve real understanding. Kieran Egan — the greatest educational thinker that almost no one’s ever heard about — points out that in some crucial ways, our language hides the world from us as much as it makes it clear. (See the “Ironic Understanding” section of my ACX book review of The Educated Mind for more.)

I.I.: Well then it’s a good thing we’ve got numbers. You can’t go wrong with an accurate number!

Maybe you can’t go wrong, but you can’t necessarily go right either — perceptually, numbers rarely “take” you anywhere. Take what I wrote above — when I said

seven million square miles

did your guts clench up with the immensity of that number… or did your eyes just skip forward, looking for something interesting? By themselves, big numbers tend to numb the mind.

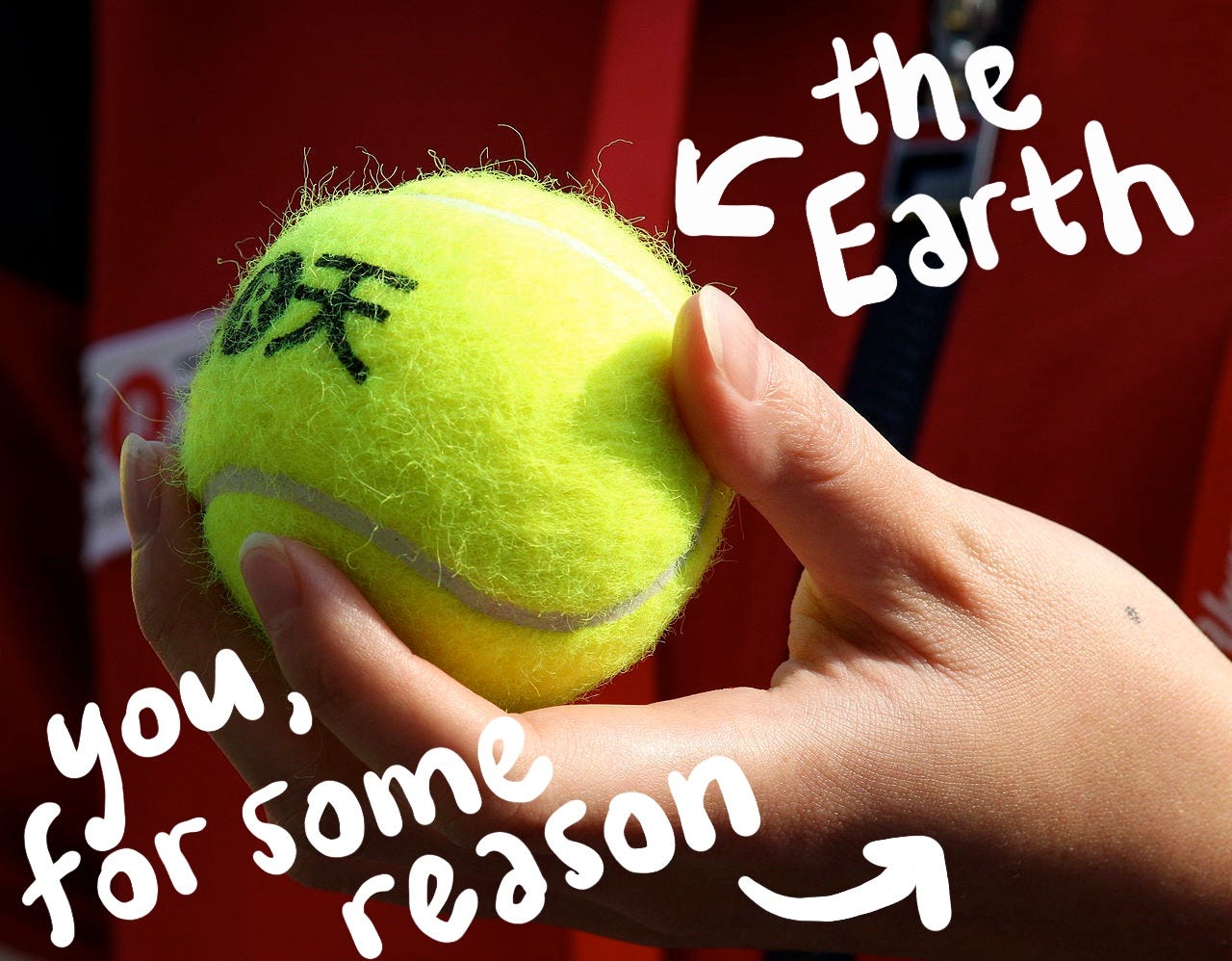

To really get a sense of the immensity of the Moon and Sun, we need something stronger — Egan would call it your “imagination”. So let’s go nuts: imagine that you suddenly start to swell up. You watch helplessly as your arms and legs and torso and head grow bigger and bigger and bigger… until you’re so big that, to you, the Earth is just the size of a tennis ball…

…and the Moon is just the size of a green pea.

Quick question: how big would you guess the Sun would seem to you, if you were that large?

Answer: as big as a green, two-story house.

Imagine placing a pea — which, once again, is the largest surface you ever look at5 — on the doorstep of that house. Now take another pea and toss it at the side of the house. Now another. THE HOUSE DOES NOT CARE. Compared to the Sun, the Moon is tiny.

I submit to you that the word “big” does not do a good job at capturing the sizes of these objects.6

I.I.: Yeah, this isn’t the first time I’ve heard clever size comparisons between astronomical objects.

Excellent! But do you hold them in your mind whenever you see the sky, or do you drop them into a box marked “science facts” and only pull them out when you’re doing pub trivia?

The ancients definitely thought that the Moon and Sun were “big” — they weren’t stupid — but their “big” was still small enough to be, say, pulled across the sky in a cart by a god. We laugh at this… but we still haven’t really updated our mental models with the discoveries that science has given us.

Which brings us to science discovery number two:

Discovery #2: the Sun is FAR

I.I.: I mean, I think I really DO know this one. It’s like 8 light minutes away. That’s far! Light is fast!

Again, this is still trivia knowledge.7 It’s another way to say “it’s 100 million miles away”, but we these distances aren’t something we can feel, because numbers this big are usually useless.

There is a way to feel it, though, and it comes every solar eclipse — even if you’re one of the millions of people who live within a few thousand miles of the path of the total eclipse. And it just requires slipping out of using numbers, and using a metaphor instead.

Among the many things that that xkcd strip had right was this —

It helps to be specific: an eclipse is like when a tall guy at the back row of the theater stands up and blocks the movie. He’s “eclipsing” the projector.

Now imagine the Moon doing that to the Sun.

Do you see what’s odd about that? They look like they’re nearly exactly the same size. A pea is blocking out a house — this sounds as stupid as a fruit fly blocking out a watermelon.

The only way this can happen is if the Sun is much, much, MUCH farther away from us than the Moon. How much? Again, to feel the distance we need to abandon the usual measurements and use metaphors.

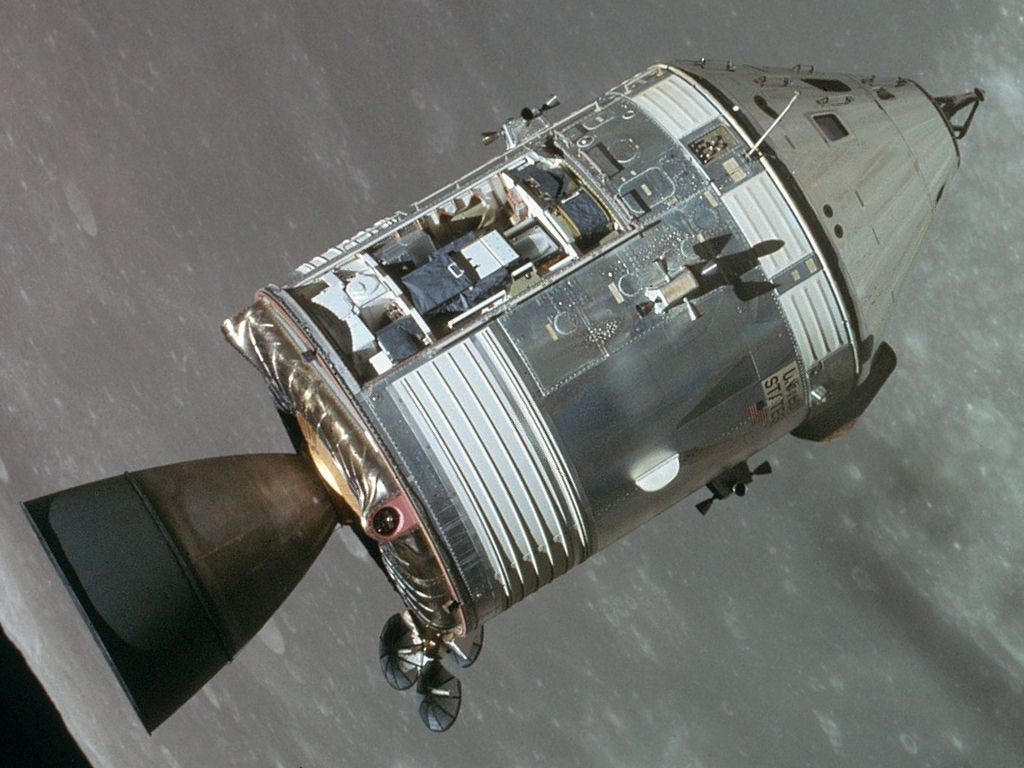

An F-22 raptor can go over twice the speed of sound — Mach 2.2. The Apollo 11 astronauts coasted toward the Moon at Mach 32… and it took them three full days to get there.

The Moon is far. But at that speed, it would have taken them six months to get to the Sun.

I.I.: I appreciate what you’re doing, but of all the many and varied experiences I have had, none included being locked in a steel can and thrown at the Sun. Got another metaphor?

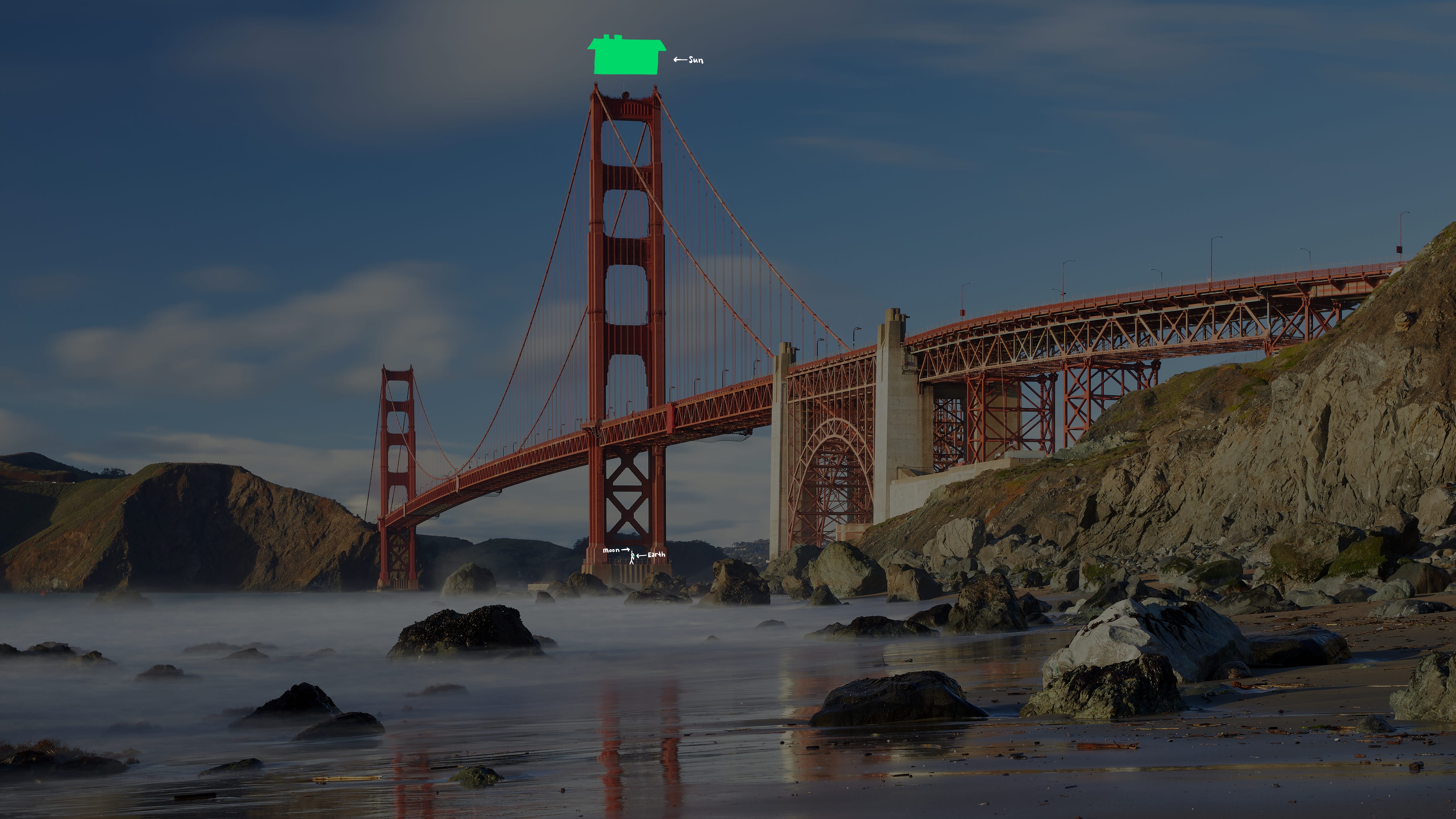

Yeah — if you swelled up again so large that the Earth was just the size of a tennis ball and the Moon a pea, you could hold the Earth against your right ear, and reach out and touch the Moon with your index finger. During an eclipse, you’d see the Moon block the Sun, and the Sun… would be up higher than the towers of the Golden Gate Bridge.

There is, by the way, a rather delicious lie baked into that metaphor; if you can’t spot it, you might enjoy an earlier post, “Your Solar System is Wrong”:

Your Solar System is wrong

Why do we care about this, again?

Even those of us who find astronomy interesting — who seek out YouTube videos on it, or take college classes in it, or even read every single xkcd8 — don’t usually apply what we learn to change how we see the world. And that’s because too many of us science teachers misunderstand our work: we assume people’s minds are empty, when in fact they’re worse than empty. We assume that our job is to fill them, when in fact our job is to explode them.

We come into school with heads filled with lies.

Cognitive scientists talk about “folk science” (sometimes called “folk physics” or “naive physics”) — the fact that we naturally make sense of what we experience with categories that aren’t true. For example:

the Earth is stationary

the heavier something is, the faster it falls

to keep moving, things need a constant push, or

roaches are intrinsically “icky”

To be fair, these beliefs are rather useful, here on the planet we’ve evolved to live in: heavier objects typically do fall faster, it really does look like the Sun rises, you wouldn’t want to lick a roach, and so on. But people used to think these things were true, full stop — and science has exploded them. (The first was taken apart by Anaximander, the second by Galileo, the third by Newton, and the fourth by Louis Pasteur.)

And yet they live. Folk science continues to be the operating system of even most curious, thoughtful, scientifically-trained people. Because of this, it’s actually difficult to state frankly the findings of modern science without sounding like a lunatic. Smells are tiny pieces of the object they come from, fractioning off into the air! Colors are really jiggles in space-goo! White light is a hallucination! Sweaters aren’t any warmer than you are, plants are just as alive as animals, and you’re never ever alone!

The reality that what two-and-a-half millennia of science has unveiled is in almost every way more strange, interesting, and (dare I say it?)9 enchanted than the dull world we think we live in.

Because of all this, when we say “science”, we’re not just talking about what people with Ph.D.’s are learning right now. The real scientific revolution — the transformation of people’s experience of the world — is still in its opening phase. But we can move closer to it. Every step we take toward building a model of the real world from the atoms on up is humbling and a little scary — add them up, and you get a real adventure.10

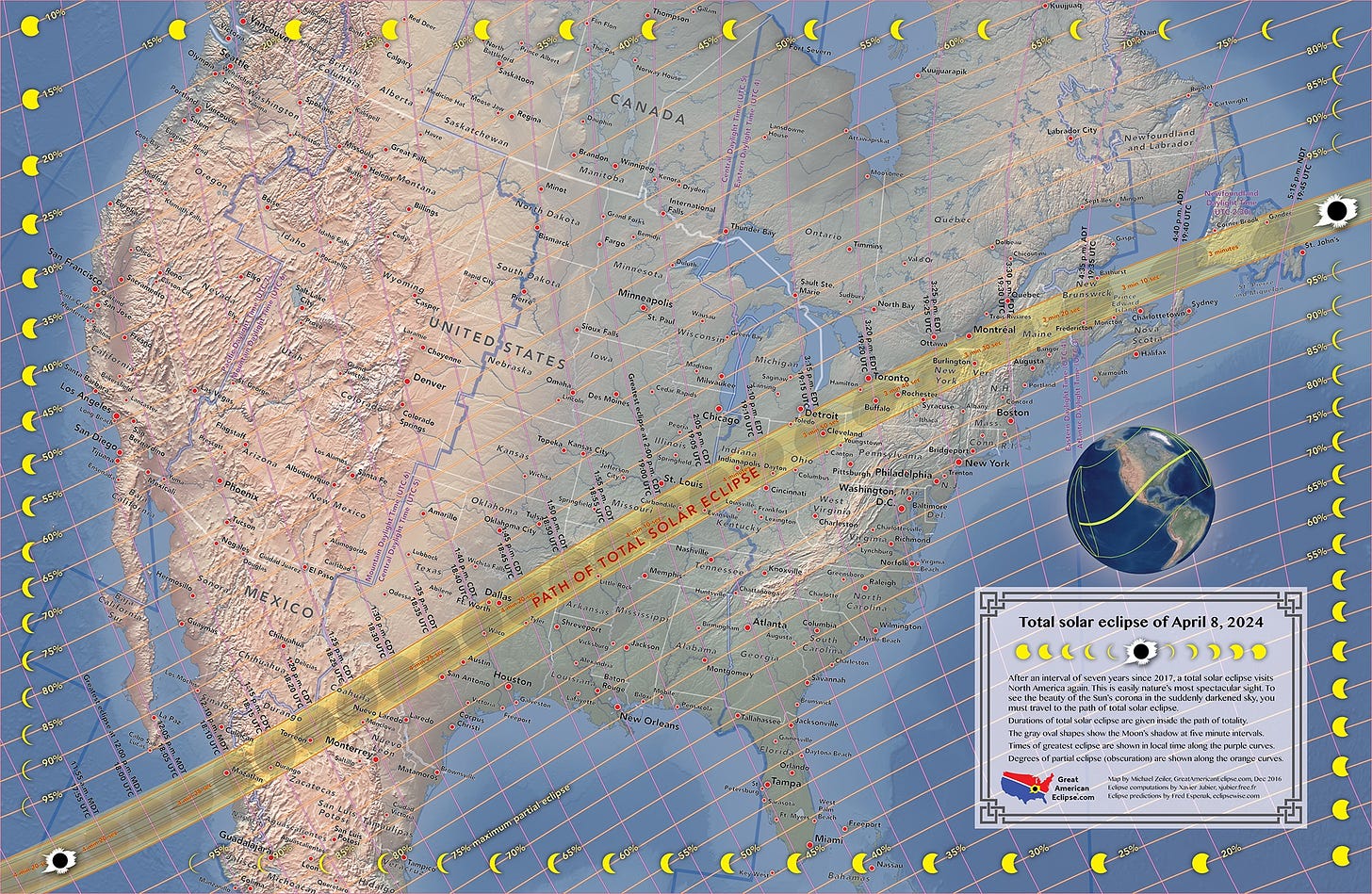

And watching a solar eclipse — even when it’s a partial one, even if you’re only in the 20% zone! — is a fantastic chance to start.

All you have to grab some of those dorky eclipse sunglasses they’re selling at your local gas station, take a couple minutes out of your day, and stare up. As you watch even a smidgen of the Moon pass between you and the Sun, try to hold it all in your head: the incredible size of the ball of the Moon. The even more incredible size of the Sun. The fathoms between us and the Moon, and the unfathomable fathoms between the Moon and the Sun.

This is one of the closest things we can get to a predictably profound moment in science, when we can use what scientists have learned to explode our ordinary ways of seeing the world, to make the incredible credible, and to fathom the unfathomable.

Happy viewing.11

Oh! If you’re interested in getting a sense for the worlds that are hidden by the binary of “big/small”, you’ll want to check out the Huang brothers’ app “The Scale of the Universe 2”.12 And if you’d like to get a sense for what “astronomical distances” feel like, I can’t recommend Josh Worth’s excellent “If the Moon Were Only 1 Pixel” enough.

Randall, thank you for giving me and my 14-year-old son something to bond over three times a week. Also, Thing Explainer needs to win a belated Pulitzer, and/or you need to be crowned God Emperor of Science Communication.

Except Alaskans. Sorry, Alaskans!

Sometimes, of course, we pick a different dividing line: “a small phone” is one smaller than we imagine the average phone to be; ditto heads of lettuce, scorpions, and Taylor Swift impersonators.

It won’t be for another couple weeks — an eclipse always happens during a “new” moon. Can you figure out why?

“But Brandon, I look at the Sun!” No you don’t: if you did, you wouldn’t be reading this.

How many U.S.’s and Canada’s, you ask, could fit on the Sun? Well, if you snipped out all the continents — North America and South America and Australia and Eurasia and Africa, you could copy and paste them twenty-thousand times on the Sun’s near side and still have room left over. Aaaaand the fact that I just resorted to using italics indicates that we’re pushing numbers beyond their natural ability to make intuitive sense to us!

Albeit some of my favorite trivia knowledge.

2,916 and counting!

I dare!

Which, in a sentence, is a pretty good summary of why I founded Science is WEIRD.

I, for one, will be roaming around the countryside of San Antonio in a minivan, looking for a gap in the clouds. Wooo! Science!!!

Here’s the link, the landing page look spamming, but just click your language and you can start using it. There’s also a free app that I use for research. (The channel Kurzgesagt has made a mostly-improved version called “The Universe in the Nutshell” that’s available for iOS and Android for a few bucks.)

I think there's an important word missing in your last sentence. Did you mean, "I can't recommend _enough_"?