One of the troubles of spreading Egan education is the foundation that it’s built on. Like I said in my Astral Codex book review of The Educated Mind, Kieran was a polymath: his system knits together

evolutionary history, anthropology, cultural history, and cognitive psychology, and tells a new big history of humanity to make sense of how education has worked in the past, and how we might make it work now.

For a lot of people, that by itself can be a barrier to entry! But if you pressed me to name the one branch of scholarship that holds his whole paradigm together, it’d have to be… Romantic poetry. And oof, if one wants to spread a new vision of education through existing schools, citing Wordsworth and Blake is probably not the most helpful direction to start off in. (There’s a reason I didn’t mention it at the start of the ACX review.)

But this can be solved. Lately I’ve been working hard with two experts to set Egan on a new foundation: the evolution of the brain.

Imaginary Interlocutor: How confident are you that Egan actually does make sense on the level of brains?

Quite.

I’m a glutton for book about the brain, and for years have had the sense of “yes, this is exactly what Egan was talking about!” But I’m a rank amateur at these fields — your shouldn’t take my word for it.

You should, however, put more trust in Barbara Oakley. Barbara has long been one of my heroes: she wrote the single greatest book on self-learning, she’s taught online courses that more than 5 million people have taken, and recently she won the McGraw Prize in Education — the other top award in education, the one that Egan didn’t win. After my review won the ACX contest, she reached out to me and quipped,

I keep reading this, and I’m like, ‘whoop, I know the neuroscience that backs that up, and I know the neuroscience that backs that up…

Imaginary Interlocutor: Aren’t you worried that you’re going to change Egan’s system?

Y’know, I was, until Alessandro called my attention to the afterword of The Educated Mind.

“What afterword?” I asked.

Because it turns out that I had never read the afterword to the book I’d spent God-only-knows-how-many-hours reading, distilling, re-distilling, teaching, and writing about. So I did. It’s only two and a half pages long, and it summarizes to: man, we really should build our educational theories on evolution.

The book’s final lines are dryly eviscerating:

Ideas about evolution transformed understanding in nearly all areas of human inquiry. Even as they began to take shape in the late nineteenth century they foundered in education because of inadequate conceptions of what aspects of human evolutionary and cultural history were being recapitulated [repeated in individual students].

Since the abandonment of recapitulation, educational thinking has persisted in a manner uninfluenced by the seismic paradigm shift that Darwin’s ideas effected in modern thinking. It may seem a lame boast to have devised a theory that manages to bring educational thinking into the late nineteenth century—but there we are.

Egan didn’t draw from the evolution of the mind as much as he might have because (1) it wasn’t his field (he was a humanities person), and (2) when his thoughts were congealing in the ’80s and ’90s no one knew that much about the evolution of the mind.

And goodness, we know so much more today. Research across disciplines (especially in neurobiology, developmental psychology, genomics, behavior ecology, and philosophy of mind) has blossomed, and begun to knit itself into general understanding. For a while this was limited to scholarly literature, but now it’s begun to spread to popular books. Some of my very favorites:

Metazoa: Animal Life and the Birth of the Mind, by Peter Godfrey-Smith

A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence, by Jeff Hawkins

Brainscapes: The Warped, Wondrous Maps Written in Your Brain — and How They Guide You, by Rebecca Scwarzlose

The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, by Iain McGilchrist

Journey of the Mind: How Thinking Emerged from Chaos, by Ogi Ogas & Sai Gaddam1

The trouble, of course, is that, as Andy Matuschak brilliantly argues in his essay “Why Books Don’t Work”… books don’t work.2 At least, reading a book (and even re-reading a book) doesn’t force the depth of cognitive engagement that you need to construct a whole new paradigm in your head.

In order to rebuild Egan’s paradigm on a new foundation, I knew that I’d need to go deeper than just reading more books. But how?

And then I found myself talking to Farid.

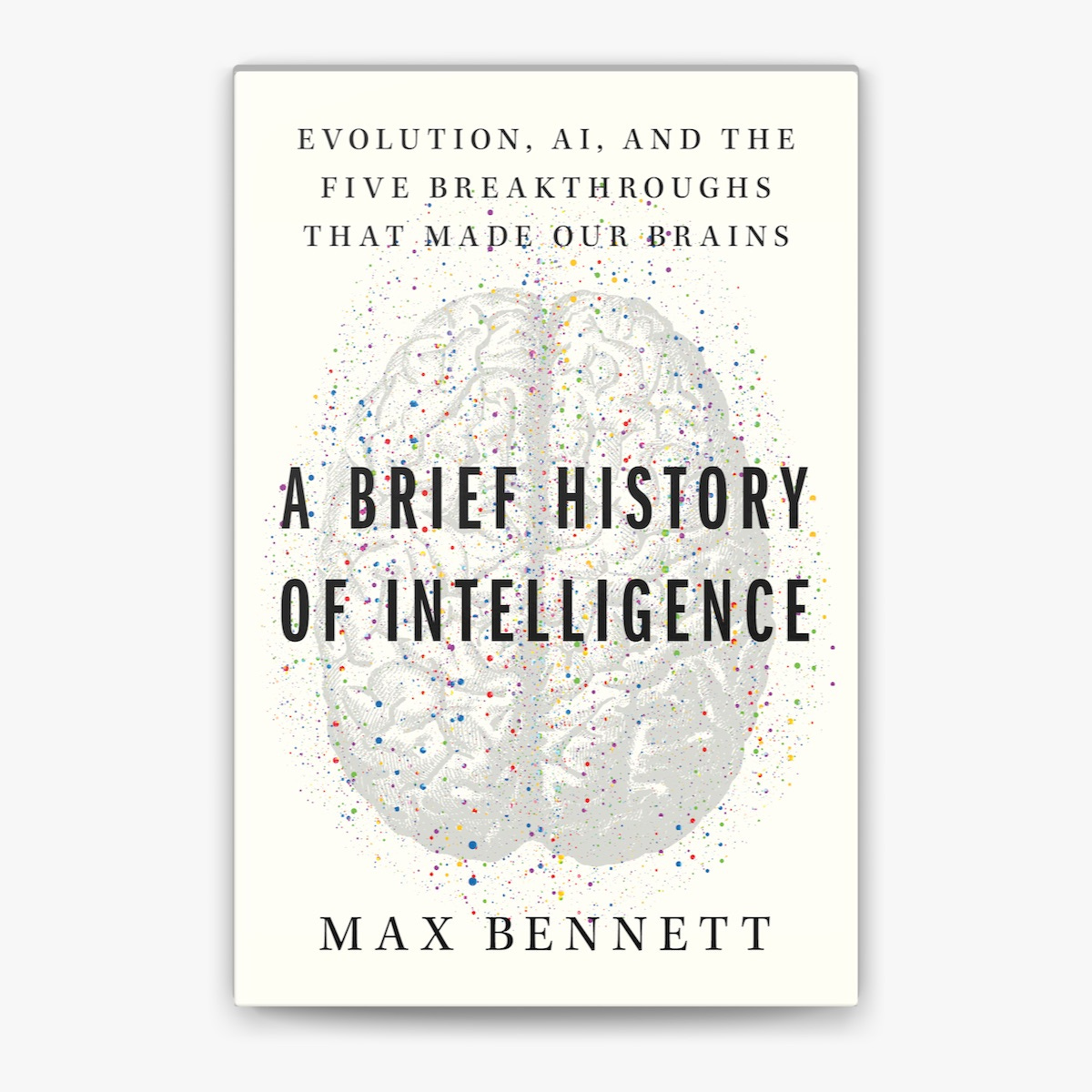

Farid Aboharb is a very clever person. He got his MD from Weill Cornell Medicine and his PhD in neuroscience from Rockefeller University.3 Presently he’s a research track psychiatry resident at the University of Pennsylvania, where he’s interested in working on neuromodulation techniques (think transcranial magnetic stimulation) and nurses a strong interest in how medical science can be taught better. He got interested in Egan from my book review, and we were talking about how Egan makes sense in terms of brain science. He suggested I read a book that’s recently been making a splash — Max Bennett’s A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs that Made Us Human — and offered to help me through it.

Holy crap is it thick with insight. And, for all that, not the easiest book to distill. So I took the method I’d honed to review The Educated Mind and applied it to this book. And now Farid and I have begun to meet!

We decided to record the meetings. If you’re a paid subscriber, and you’d like to follow along in our exploration of where the heck this is all going, be our guest!

Imaginary Interlocutor: Why brains?

Two reasons. One is as shady, sketchy, and dodgy as all heck, and the other is solid. The shady one: brain science is a credibility cheat code. If we say something that sounds unusual about education — say, “six-year-olds should start memorizing poetry” — people can just roll their eyes and ignore it. But if we append that with a really cool fact about brains, then many people will begin to pay attention.

I.I.: You’re right — that really does seem shady!

Egan thought so, too. In fact, he agreed so strongly that he all-but-refused to engage with educational psychology. This is one of the biggest reasons Egan education isn’t widespread.

The better reason to try to communicate Egan through brain science is that, in the end, literally everything in education really does cash out into brain science. Every memory you make and feeling you experience is the subjective counterpart of something objectively going on in your brain. Very, very much of what’s called “brain science” in education is malarkey, baloney, hogwash. (There’s a reason I often abbreviate it “BS” in my notebook.) But that’s no reason to avoid doing it well.

Egan shook his head at people who attempted to reduce education to applied psychology, and I agree — our vision of what we want our kids to become can’t be found by peering into their heads. But psychology gives us a solid grounding to understand what’s happening in education, and at the end of the day, psychology is about what’s happening in the brain.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Okay, I understand why you want to focus on brains. But why evolution?

The human brain is the most complex structure in the known Universe. Inside your head are nearly 100 billion neurons, each of which can connect to 10,000 other neurons, forming something north of 100 trillion connections. It’s too much to take in.

But hidden inside your three pound gelatin is a literal story. The different structures of the brain evolved in order to solve problems that our evolutionary ancestors were facing. And, as Egan never tired of saying, 🧙♂️STORIES are a powerful way to make sense of a too-complex world.

Imaginary Interlocutor: What’s the story?

That’s what Farid and I are attempting to distill. It’s… harder work than I had thought. Bennett’s book tells the evolutionary story in five acts: nematodes, fish, early mammals, early simians, and humans. (Borrowing a page from

’s superb Grandmother Fish, I’ve taken to calling these “Grandma Worm”, “Grandma Fish”, “Grandma Mouse”, and “Grandma Monkey”.)Eventually, we’ll be presenting all this publicly. If you’d like, though, to watch this emerge, I’ll share the recordings of our meetings to paid subscribers. I’ll also share the link to the Google Doc in which I’m distilling the book — replete with possible Egan tools (some new!) that emerged in each evolutionary step.

I.I: New Egan tools?

Egan’s paradigm is incomplete; he always said as much. My ultimate hope for our process isn’t just that we’re able to explain Egan’s approach better, but that we’re able to understand it more deeply. Right now, I’m tremendously hopeful!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Lost Tools of Learning to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.