(Quick note — tonight, our final AI livestream will be experimentally held on YouTube. You don’t need a password or anything — just show up to the Science is WEIRD channel, and start suggesting boring topics in geography you want to find fascinating! 9pm Eastern / 6pm Pacific.)

1. A problem

As they enter adolescence, lots of kids spontaneously develop a lust for the mysterious, the weird, and the eerie. Meanwhile, in middle school, they’re learning about pulleys.

2. Basic plan

Prompt middle schoolers to study “cryptids” — rumored creatures like the Loch Ness Monster, the Chupacabra, and the Yeti.1 Provide responsible books that lay out the best evidence and assess it rationally, and give them lots of opportunities to argue about them.

3. What you might see

A kid gleefully turning page after page of yet another book on (for example) Mokele Mbembe, the long-necked dinosaur that supposedly lives in the Congo.

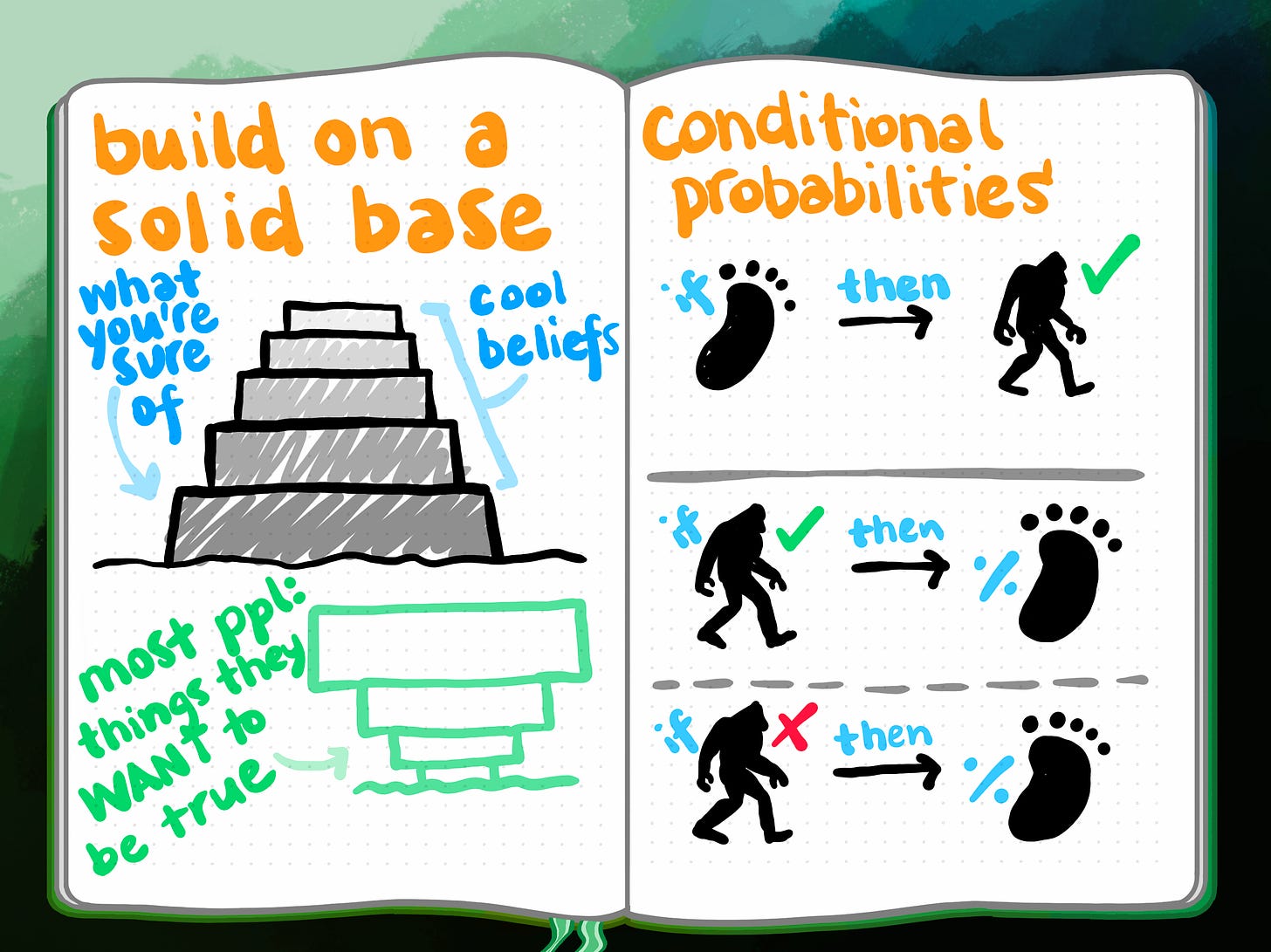

As they wrestle with competing views, kids discussing confirmation bias, epistemic humility, and probability calibration than some people glean from Eliezer Yudkowsky’s entire Sequences. Eventually, some kids challenging others to draw Bayes’ boxes.

4. Why?

Cryptids are training wheels for the rational mind.

We’re all suckers until we’ve discover we’ve been fooled a few times… and we don’t want our kids to be suckers! The world seems increasingly filled with unhinged ideologies and dangerous conspiracy theories; we want to help them find their footing in the real world.

As Richard Feynman said, in his commencement speech at Caltech:

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself,

and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Therefore, it seems like we should give our kids more opportunities to be fooled. Obviously, this is playing with fire, but compared to most of the other conspiracy theories or false beliefs out there, cryptids are mostly harmless.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

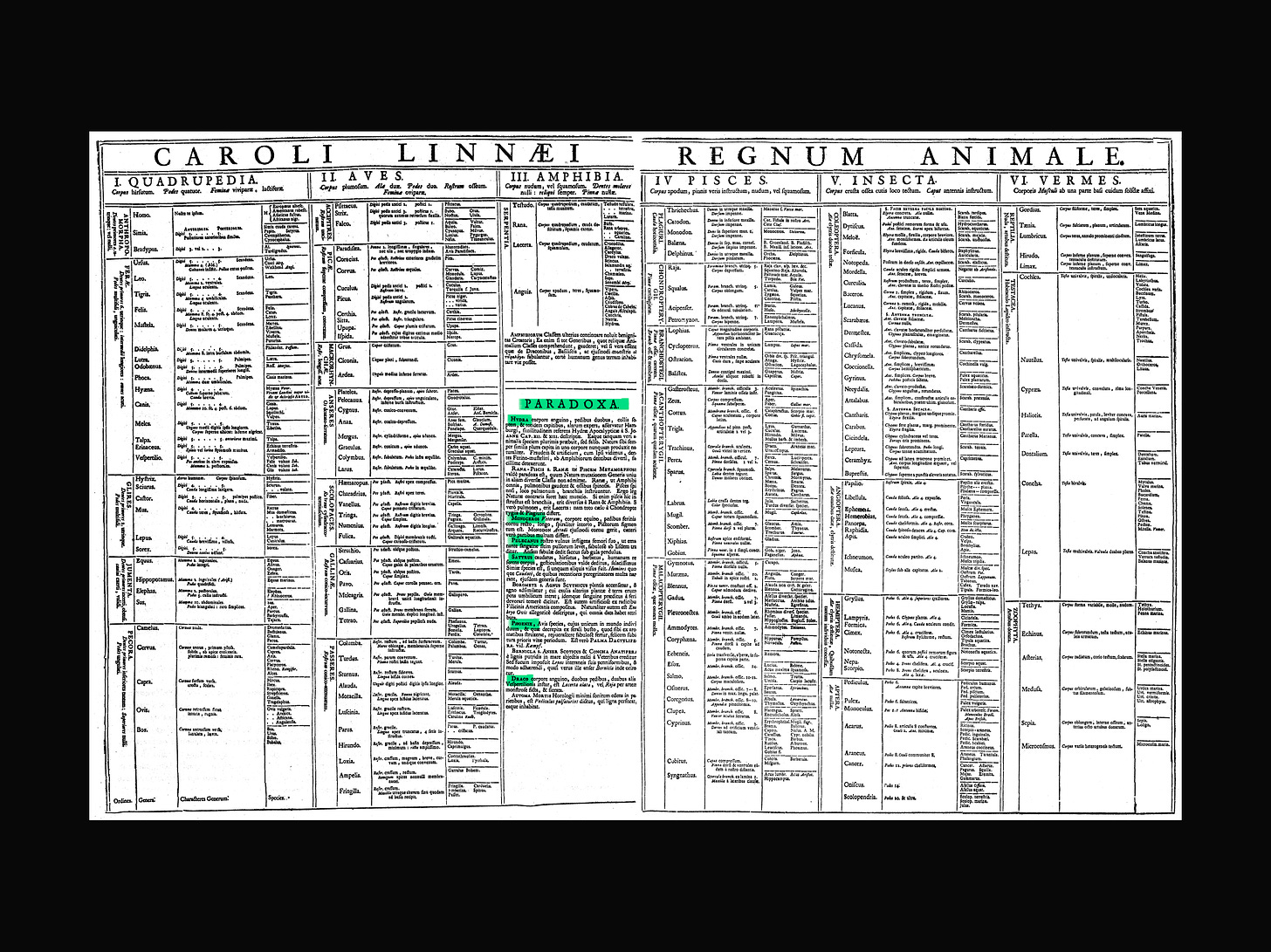

Many serious science-types snub “pseudoscience”, but it’s what gave birth to modern science. The proto-biologists of the 1600s in particular were cryptid-crazy, and this was wonderful: they were embarked on a holy quest to sort truth from fiction and delineate the boundaries of science.

If many scientists today seem uncomfortable with the uncanny world of possibly mythical creatures, that’s less a statement about what science essentially is and more about what the culture of professional science happens to look like at this particular moment.

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

Cryptozoology bridges the MYTHIC (🧙♂️) and the PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) by interrogating 🧙♂️FANTASY with the tools of rationality.

Does this make it ROMANTIC (🦹♂️) understanding? I think so. Emotionally, it’s grounded in a lust for 🦹♂️THE STRANGE. And when I read cryptozoologists, I’m struck by the 🦹♂️AWE they seem to feel when they imagine a creature from the distant past (be it an Brontosaurus or a Gigantopithecus) still walking around the world today — heck, I can feel the shiver up my own spine!

When this connects with a student, it can even propel them beyond PHILOSOPHIC understanding into IRONIC (😏): at the end of the day, we can’t say that Bigfoot definitely does or doesn’t exist — the best we can do is give probabilities, and live in doubt. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

6. This might be especially useful for…

Weirdos.

7. Critical questions

Q: Why study cryptids, rather than (say) psychic abilities, ghosts, or UFOs?

Why not all of them?

Studying science seriously means figuring out its limits, which means discussing what’s outside them. This, in fact, is part of how science developed in the first place. (You used to be able to find lots of mainstream scientists who were excited to talk about the evidence for Martians, clairvoyance, and ghosts.)

Among these, however, cryptids should have a place of privilege in the curriculum, because (1) kids love animals, and (2) they don’t press hot-button topics like the existence of soul, life after death, and humanity’s place in the universe. (Or at least they press them less.) Maybe we’ll make patterns for the others later — they’d probably go in the high school curriculum.

Q: But wouldn’t precious class time be better spent talking about atoms and molecules and the other things we know exist? Aren’t cryptids just a distraction from real science?

No: they’re a doorway.

I learned far more about geology, biology, and physics from engaging with young-earth creationism when I was in middle and high school than I learned in all of my science classes combined. And something similar was true with my elementary school interests in Nessie.

Q: How? How could that be true?

Partly it’s because discussing things that aren’t true rockets you past subject-specific knowledge (because there isn’t much subject-specific knowledge about, say, Loch Ness Monsters) and drops you into the higher moves of scientific thinking: evaluating evidence, considering alternate theories, questioning sources, and so forth.

But partly it’s also because these topics are weird and interesting. (And everyone loves an 👩🔬IDEA FIGHT.)

Q: But what if kids start believing in cryptids?

Congratulate them for changing their minds! For many kids, this will be part of the process. But don’t let that belief moulder — with kindness and respect, prompt them to explain why they believe what they do, and guide them to keep updating.

Q: Sure, but what if they KEEP believing in cryptids?

Then they’ll be in good company: Jane Goodall is an outspoken believer in Bigfoot. David Attenborough suspects the Yeti might be real.

Q: Oh, come on. You talk as if these beliefs are fine, but you know these things don’t exist.

Well, I strongly suspect none of the ones I’ve listed exist, but that means I’m in the minority. A majority of modern people believe that some paranormal things are real — and quite a lot of people claim to have experienced these things.

70% of Australians said they think they’ve had an experience with the paranormal. A quarter of Americans claim to have seen a ghost. And sticking just to cryptids, if you’re in North America, ask friends who like to hike whether they know of anyone who thinks they’ve seen Bigfoot.

Heck, my great-uncle swore up and down he had watched pterosaurs while fishing on a boat off the coast of Mexico. When he asked the captain about them, he said, the man shrugged — yeah, we see those all the time.

I bring this up not because experiences like this are particularly strong evidence that these sorts of things exist, but that it’s actually normal to believe in the “paranormal”. Statistically, it’s people who believe in none of it who are the odd ones out.

It’s strong evidence that pterosaurs are still alive, but because it shows that it’s really rather common that people experience cryptids and other “paranormal” things.

This isn’t to say that they’re right about any of this — it means that, insofar as one wants to engage kids where they are, it seems right to take these possibilities seriously enough to talk about them.

If we’re not helping kids use science to make sense of personal beliefs, we’re not really teaching kids science.

Q: I’m worried that this will make kids too skeptical — that this’ll make ALL beliefs seem stupid.

This is a crucial question, and it deserves more time than I can give it here — look forward to a rollicking discussion post about skepticism, religion, and fundamentalism!

Studying cryptids is playing with fire, and it’s fun to play with fire! But maybe, um, it’s dangerous, too? Become a subscriber and join in the comments conversation.

8. Physical space

Nothing’s particularly necessary here… though I’ll say that there’s no experience quite so disillusioning of Nessie than actually going to Scotland and talking with the people who live in Inverness.

9. Who else is doing this?

First and foremost, the paleontologist Darren Naish is so good with this. (If you doubt that rationality can lead to exquisite joy, take a look at his Twitter thread on Bigfoot.)

But also, me, actually! Last summer I started a series of courses for kids (titled “Believe It Or Not”) on how to become rational, and the first topic was “Bigfoot”. Next summer, it’ll be sea monsters. The summers after that, it’ll be UFOs, psychic phenomena, and ghosts.2

And, dang it, they’re good courses: in “Bigfoot”, kids learn…

how to think about probabilities

how to set a base rate wisely

when to trust experts, and how to think about anecdotes

how to update their beliefs sensibly

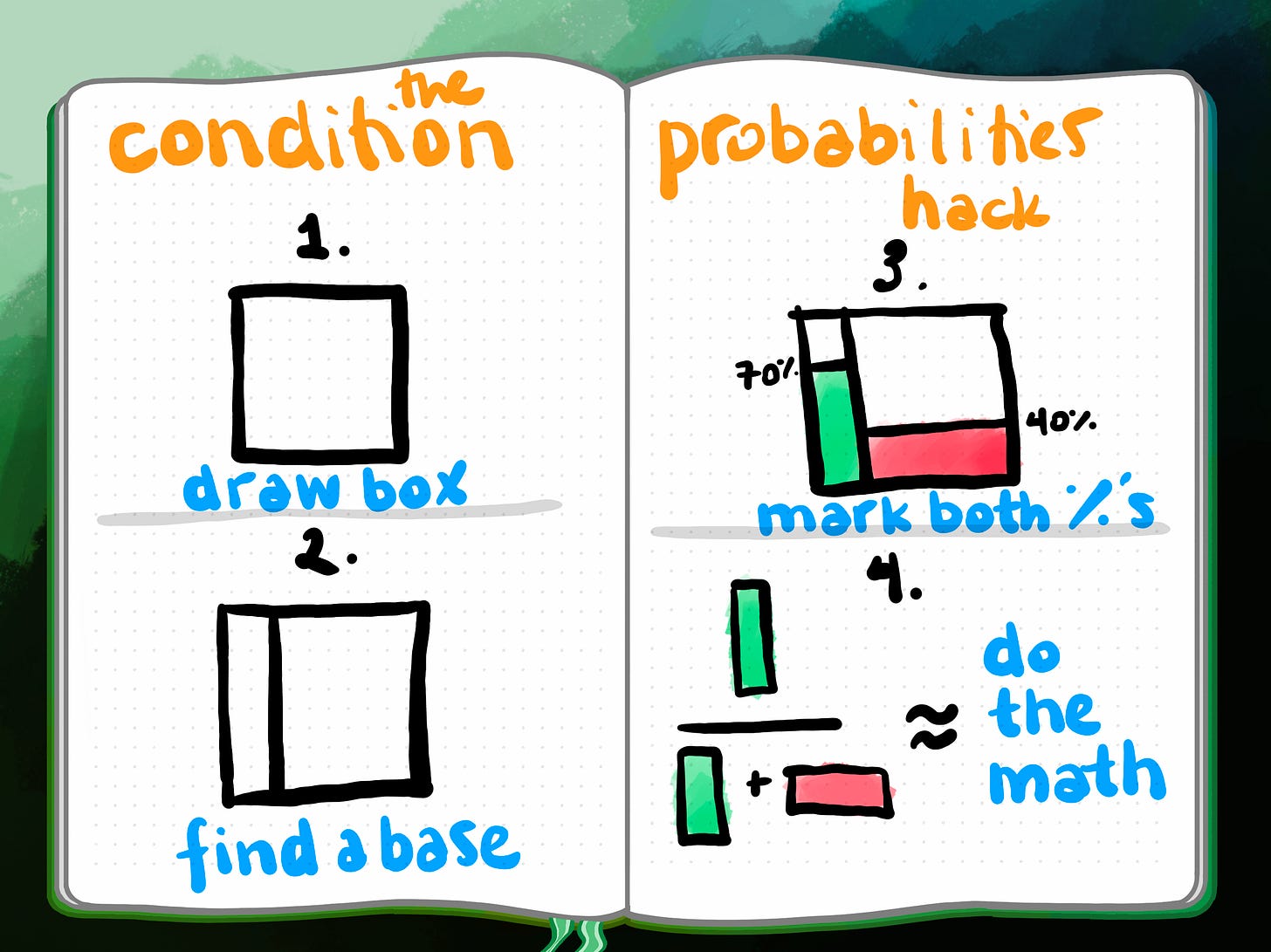

By the end, kids are actually doing Bayesian calculations by drawing Bayes boxes3 and doing the arithmetic. (Is there only a 1% chance that Bigfoot exists, or a 0.0001% chance? If these sound the same to you, I’ll tell you that this summer I moved from one of them to the other — I won’t say in which direction — and I’ll tell you there’s a world of difference between them.)

But in preparing this course, I was able to draw from the zillions of books, YouTube channels, and podcasts that cover cryptids in an intellectually responsible way. (If you’re looking for a book, my favorite is Abominable Science!: Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and Other Famous Cryptids by Daniel Loxton & Donald Prothero. If you’re looking for a podcast, my favorite is Wild Thing, hosted by Laura Krantz. And if you’re looking for a YouTube channel, Trey the Explainer is so wonderful.)

How might we start small, now?

I’m happy to offer up my “Believe It Or Not” curriculum to anyone who’d like to use this in schools! In the meantime, you might want to start reading Tom Chivers’s Everything Is Predictable: How Bayesian Statistics Explain Our World to get a sense of where this is all heading.

10. Related patterns

This is an example of A Special Place for Animals°, but it’s nearly the opposite of Biology of Imaginary Creatures°, which imagines that a creature (like a dragon, or King Kong) is real, and then tries to figure out how it might actually work.

Though young-earth creationists are sometimes the biggest boosters of cryptids, this is a wonderful way of supporting Evolution Throughout°, because it’s an opportunity to talk seriously about whether (say) finding a sauropod in the Congo would actually upset our view of evolution.4

Most importantly, though, it’s our big step into Estimating Your Understanding°, which is to say, teaching kids to move past thinking that the answers to all important questions are (1) simple or (2) unknowable. It’s where we’ll get all Bayesian on stuff… which will have profound consequences for the whole high school curriculum.

Afterword:

I have a post in me about how to teach Bayesian reasoning to middle school kids. It’s all sketched out, with illustrations and whatnot — I’ve been thinking of writing it for LessWrong, the spiritual home of the rationalist community. Alas, who has the time to write? I remain so very, very grateful for all of you who chip in $5 a month to encourage me to invest time in this, and to all of you who share these patterns with communities who are interested in the random things they touch on.

Not Bigfoot; he’s real.

I’ve taught a course on UFOs before, which you can still find on the Science is WEIRD website. I stand by it, but when we swing back to the topic, we’ll be engaging the evidence with all the tools we’ve learned from Bigfoot and Sea Monsters.

This is a way of doing Bayesian calculations inspired by the YouTube channel 3Blue1Brown that actually makes intuitive sense, and requires no algebra. Look for a post on this at some point in the future.

It wouldn’t. (Creationists, you have better arguments than this!)

I believe with (95% probability) that this is a typo:

> It’s strong evidence that pterosaurs are still alive

Not?

This would be a great summer or winter break course. Putting together the recordings into one stack, for purchase would be excellent. This particular blog entry is a great source for the explanation/marketing of it.