Pairs well with “Comments on the comments on the book review (part 1)”, which in turn pairs well with the actual book review, but that’s long, and you’re probably very busy.

6. Comments in favor of pain

Some readers interpreted Egan as a touchy-feeling Romantic softie who, prancing about a meadow, proclaimed that education should be natural and easy:

Despite the assurances to the contrary, this is just another progressive education theory that tries to get around unpopular and unpleasant approach such as rote learning

That’s definitely not what Egan’s saying — and if you’ve been riding along the Egan train so far imagining that good education can be uniformly pleasant, I’m sorry to have to pull the brakes, hard.

Egan thinks that a good education requires more difficulty and more discomfort than most students get.1 In his book Primary Understanding, he writes

Becoming educated is a kind of adventure. It has its difficulties, dangers, losses, and it has its rewards.

Adventure isn’t hobbits bopping around the Shire; it’s leaving comfort, being pressed into suffering, being forced to sacrifice pieces of yourself that frankly you’d prefer not to lose.

Why? To do something meaningful.

One trouble with the dominant model of schooling2 is that we demand kids master new domains — that is, do unpleasant things — without helping them feel those things are worthwhile for them.

The promise of an Egan education is that it lets us combine mastery with meaning.

Let’s set the scene: a young woman is sitting at a desk in Geometry. In front of her is yet another failed attempt to create a proof of the Alternate Interior Angles Theorem. She’s thumbing her phone under the desk when you, the teacher, walk by and gently redirect her to her work. She turns up from TikTok, looks at you straight in the eye and asks, “why do I need to learn this?”

The classroom is suddenly quieter; the same students whose attention you have been struggling to attract for weeks now are showering you with the stuff.

Okay. Deep breath. Let’s take three examples of how you might respond and weigh their plusses and minuses.

Response #1:

You’ll need to know this when you’re older!

Pros: Short, memorable. Has a nice prosody.

Con: Obvious bullshit.

Response #2:

This develops your analytical thinking skills!

Pro: Hard to prove wrong!3

Con: Might just make the student hate analytical thinking.

Response #3:

If you don’t know this, you’ll probably fail this week’s quiz!

Pro: True, alas.

Con: You’ve just sold your soul.

As a high school geometry teacher, wouldn’t you appreciate it if this student’s education had helped her internalize mathematics as mattering? If she had been raised on the stories of great mathematical breakthroughs, if she saw how the invention of modern math upended the whole world, if she was part of a thick culture in which it was normal to enjoy math, and take it seriously?

Meaning makes it easier to do hard things.

Do I think that we can make every kid fall in love with mathematics? No. (Kids, once again, are very different than each other.) Do I think we can help almost every kid find mathematics more meaningful than they currently do? Heck yes.

7. Comments about chimpanzees

In the review, I had written:

We can see it if we ask, what can a hunter-gatherer deaf-mute child who’s not yet learned to sign do… that a chimpanzee can’t?

The answer turns out to be quite a lot! She can play the games other kids play, she can figure out her group’s social organization, act out her social role, and learn toolmaking. How can she do this, without language, Egan asks? Mimesis. We are the apes who imitate. “Monkey see, monkey do” is more true of us than actual monkeys; we’re parrots who intuit the meaning of the things we’re repeating. Though Homo sapiens has used language for around 50,000 years, we’ve been around for at least four times that long — and we survived by copying each other. Mimesis, more than words, is the anchor of our uniquely human way of being in the world.

One commenter compliments the review as a whole, but adds:

The only issue I had was that I'm like 99.9% sure that a chimpanzee “can play the games other [chimps] play, she can figure out her group’s social organization, act out her social role, and learn toolmaking.” In fact I'd argue the average chimp is better at these than the most autistic .1% of humans.

I appreciate this, and realize that to understand the big story of our cognition, I should really get a clearer picture of our current understanding of chimp thinking.

If anyone has a recommendation for a specific book chapter, online article, or video I should watch, let me know — I’ll look at it, and write a post about this later.

8. Comments suggesting that most young children are NOT in fact idiots

Maybe I’m too much of a STEMlord, but I’m highly skeptical that abstract/general logic is a weakness of children and that it should be pushed off until high school. I attribute a lot of my academic success to getting a really early appreciation for picking out patterns and connections in things.

You could probably weave this kind of stuff into an Eganian story-centric approach — science is filled with people who made discoveries by drawing on their other experiences and domains. But I think it’s much more efficient to teach kids things they can use, to give them immediate sensory evidence that they have something they didn’t have before.

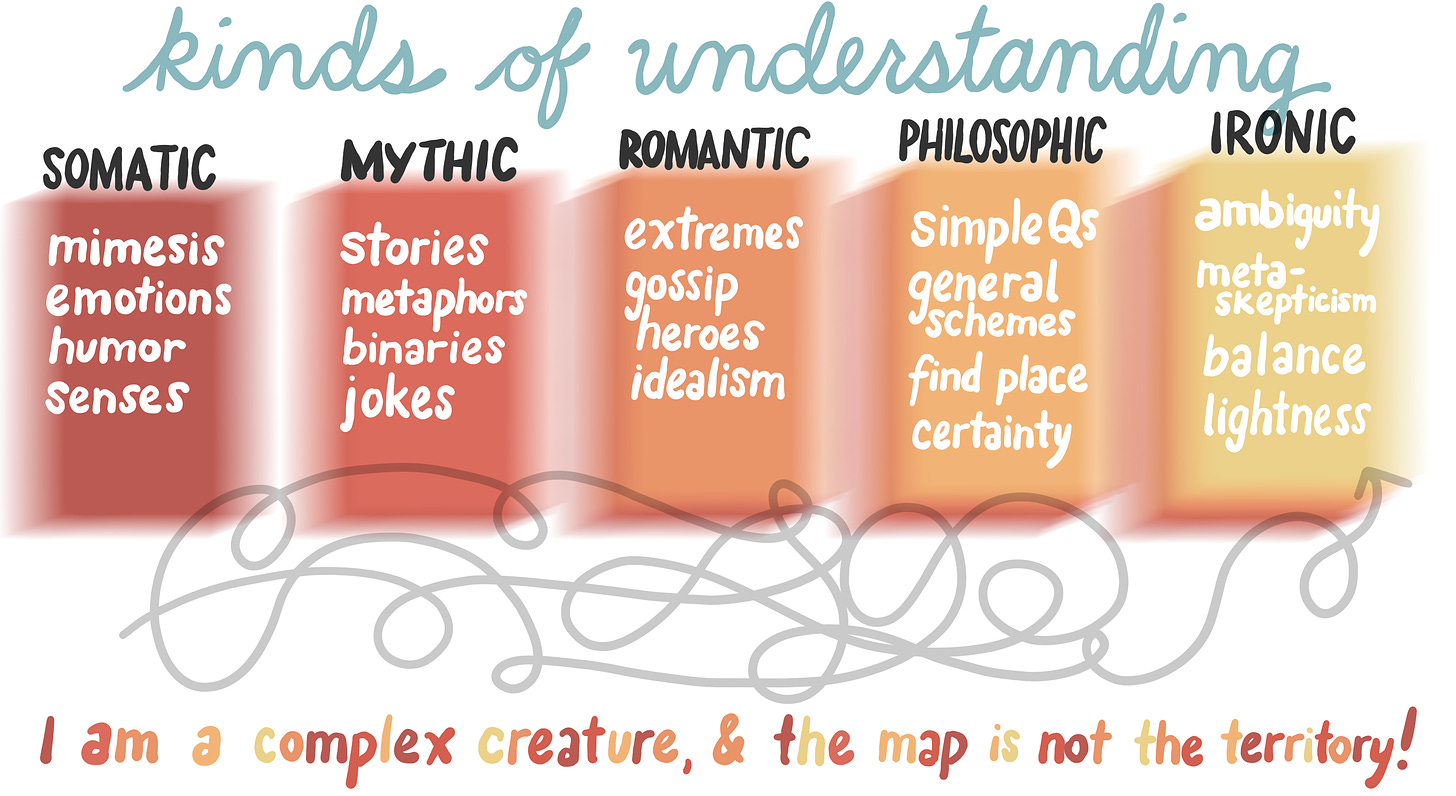

I really appreciated this comment — and I agree that this was a flaw in my book review. A philosophy-minded friend (Alessandro Gelmi, who’s completing his PhD and is working to popularize Egan in Italy) criticized it for the same thing. When he helps classroom teachers understand Egan, he finds that they frequently misinterpret his system as a rigid theory of development. They’re prone to imagining Egan saying something like “when children are 3–8, use the Mythic toolkit, when they turn 9 use the Romantic, and hold off on doing too much Philosophic stuff until they’re 15”.

This is probably because rigid theories of development are thick on the ground in educational psychology classrooms.

Now, I’m pretty sure I never said anything like this in the review. In fact, near the end I tried to destroy this misunderstanding by specifically denying it, and then blurring together all my previously-sharp categories:

Alessandro granted all this, but was still worried that, because I had presented the kinds of understanding in order, I was going to to confuse people into thinking that an Egan education would hold back Philosophic things like “logic” and “rationality”.

And his worry wasn’t academic. The real danger here, he warned me, is that this misapprehension of Egan could make schools less intellectual than they currently are! If we scrape out the ideas from elementary school (however poorly grasped they currently are) and put stories in their place, kids could be even further away from Philosophic understanding.4

I argued back: first, Egan laid these out in the same way, and second, his theory is already wonky enough — if we present it in its totality all at the same time, no one will ever understand it EVER.

Anyhow, that was months ago. Now the smoke has cleared aaaaaand… it seems Alessandro was right. Sigh. At least some folks read the review and walked away thinking “Egan says we should hold back the abstract, logical stuff until kids are old.”

So, in the hopes of clearing this up, let me state this using the most hardcore, pathologically clear tools I know about: bullet points.

According to Egan:

all kids can (and do) work with abstract concepts, and this should be a part of schooling from the beginning

all ages of people are working with all the kinds of understanding all the time — what changes as kids age is which kind of understanding bears most of the weight

some young kids especially crave abstract concepts; they shouldn’t be “held back” because they’re young

a good classroom teacher understands their students individually, and can gear instruction to help them get what they need

But it’s also not a race to see who can get the most Philosophic understanding first. The other kinds of understanding aren’t steps to be trod upon and then kicked away; a well-educated mind is one that keeps as much of Somatic, Mythic, and Romantic understanding alive as possible.

Oh, and a big pointer from Alessandro: I sometimes say that Egan’s approach is “story-based”, and that’s true. (One of Egan’s more readable books is even titled Teaching as Storytelling.5) However, that doesn’t mean that he urges teachers to just tell a bunch of stories. Rather, it means that, when we look to teach a topic, we should borrow from a storyteller’s toolbox — emotional binaries, vivid mental images, mystery, agents and actions, heroics, increasing stakes, ironic reversals, surprising conclusions, and so on.

(That said, narrating stories is quite useful.)

9. Comments recommending DOING stuff, not just FEELING stuff

The same commenter continues:

…This is why the part about favorite “affective experiences” over “doing stuff” especially sticks out to me — kids love doing stuff!… A lot of the Eganian lessons you depict do sound like they would have been more fun and engaging to me than normal school, but it’s much less clear to me that I’d have retained them any better or that I’d end up any smarter, especially without having pre-existing scientist mentality to tie it all together.

Absolutely — and this demonstrates a (stupid) bias that I have against “hands-on learning”.

Oh, I can rationalize my bias: I’ve haven’t merely witnessed teachers doing “hands-on learning” brainlessly, I’ve been one of those teachers. (I remember the day I tried to teach a tutoring client about fractions by baking cookies. Both the learning and the baked goods were mediocre in equal measure.) Afterwards I’ve heard many teachers preach the Gospel of Hands-On Learning, and have rolled my eyes hard.

But, look: hands-on learning is often great. There are some things that can only be learned with one’s hands, and other things that can be helped. I’ve thrown out the baby with the bathwater. I am guilty. And I have a sneaking suspicion that Egan was also guilty of this… and recognized it.

In one or another of his books, he has a fictional teacher point out that hands-on learning can be meaningful — that, for example, actually going to Gettysburg is more affecting than just reading about the place.

In his book, Egan replies that if a student knows the story of Gettysburg, and then visits it, it can be a quasi-religious experience. (I imagine a student listening to a tour guide, rapt: “Look over there, to Little Round Top, and imagine Joseph Chamberlain’s 20th Maine Regiment are a little more tired, a little less courageous. As they watch Confederates march up the hill, they hear their commander ordering a bayonet charge — and they hesitate. Now look over there as the Union’s left flank breaks. Look over there as the Confederates hook around the Union line. And picture President Lincoln, four months later, giving a very different speech… and imagine slavery continuing in the Americas another generation, then another, then another, down to the present day…”)

Without knowing its story, Gettysburg is just another park.

I wonder if this could serve as a rule of thumb:

when a hands-on activity makes learning more meaningful,

more clear,

or more memorable,

it’s good.

10. Comments suggesting that, perhaps, the review was too long?

And how!

11. Comments noting that the review should have been longer, because the Somatic was given short shrift

Your scant mention of somatic understanding is like sending kids into the ocean without teaching them to swim. We're not just shaping minds here, we're crafting souls, and by sidelining the somatic, you're setting up our children for an emotional and psychological famine. Your omission isn't just a gap; it's a black hole swallowing the holistic growth of our next generation. Imagine kids divorced from their bodies, stumbling through life with the grace of a marionette whose strings have been cut! Your oversight is a ticking time bomb, threatening to blast a crater in the holistic development of our children, leaving them ill-equipped to engage with the turbulent, chaotic wonder that is life. You're not just ignoring a chapter in the book of understanding; you're burning it!

Okay, full disclosure: there were a lot of comments, and I can’t, right now, find the spot where people were talking about this. The above is something I had ChatGPT cook up.

But anyhow: I agree whole-heartedly! And in fact all of us are backed up by quite a few of of Egan’s long-time collaborators, who were much harder on him than I was.

The wonderful Annabelle Cant, who moved from Romania to British Columbia to study under Egan, lambastes him for spending so little space on Somatic — of the five kinds of understanding, it gets a scant six percent of the mentions. (This is from her book, Unswaddling Pedagogy. Never one to reject critique, Egan blurbed it enthusiastically.)6

Let me state this frankly: I think maximizing Somatic education is one of the most powerful projects that a would-be movement of Egan schools could take on. And we don’t have to start from a blank slate: another of Egan’s collaborators, Mark Fettes, has spent much of his career opening up space for Somatic understanding in the framework. In his article “Imagination and Experience”, he argues that Somatic understanding threads its tendrils through all kinds of understanding and is much more important than Egan’s framework acknowledged. He suggests that, once we understand this, Eganian instructors can begin to have fruitful conversations with (among other groups) ecological guides, indigenous educators, and Waldorf teachers.

This is, by the way, a part of the project that I suspect folk in the post-rationalist community — you know who you are! — might find up their alley. If you’re interested in talking, drop me a line.

Whither, now?

An Egan approach opens the door to helping even quite young kids understand some deep concepts that most science-literate adults don’t know. Next weekend, look for a post on how every diagram of the Solar System is wrong (and not in the way you think).

I’m holding back from saying all students, because goodness, have you met academically-minded high schoolers lately? I used to be a test-prep coach, and dang the kids are not alright.

Some might say this is the matter with schools.

Especially if your students struggle with analytical proofs.

I’m told this is a mistake that Waldorf schools make when teaching math to little kids: they tell stories about subtraction and multiplication that hide what’s really going on, rather than reveal it. If anyone more conversant with the Waldorf tradition would like to correct me on this, please reach out. I really need to understand Waldorf better.

If you work with elementary-aged kids, this might be the book for you. It’s like Primary Understanding, but shorter, less theory-laden, and more immediately practical. (And — wow — it doesn’t sell for two hundred dollars!)

She’s truly a wonderful person. Years ago, when I drove up to Simon Fraser University to meet with Kieran without (it turns out) actually confirming that he was in the country at the time, she spent hours answering my questions, and even wrangled Kieran into having a phone call with me.