Halfway through last week’s “Why I am not a classical educator”, I said something rather peculiar…

Understanding the Universe is, for lack of a better word, spiritual work.

A real science education, I said, should be spiritual. Remarkably, nobody called me on that!

Imaginary Interlocutor: Should we have?

I mean, it’s definitely an odd thing to say. And potentially dangerous for a fledgling educational movement: it might miscommunicate what we’re trying to do and scare away natural allies. So I’d like to use the comments section here to explore how people react to this, and brainstorm how we can express this goal of Egan education better. (And I’m especially interested in hearing the hunches of folk who are new to the blog, or who don’t comment much.)

I.I.: And, just to be clear, does this originate with Egan, or just with you?

That all aspects of the curriculum should engage something that could be called “spiritual” is definitely orthodox Eganism — though he vacillated between emphasizing and de-emphasizing it, depending on the audience. (I definitely de-emphasized it in my ACX review.) My favorite example of this comes in a question-and-answer section of The Educated Mind, when a fan suggests that she’s found a sixth kind of understanding: “spiritual”.1

Egan responds that, nope, “spiritual” isn’t a different kind of understanding to be tacked on — it’s what we call some of the core experiences in every kind of understanding. It’s already built into what we mean by being educated.

1. What we’re not saying

I.I.: What do you mean by “science class should be ‘spiritual’”?

“Spiritual” is famously hard to define, so let me start by stating what I don’t mean.

I don’t mean that a science class should introduce “spirit” in addition to atoms and molecules and such. (Once again, Sam Harris is a helpful model here. In Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality without Religion, he defends the right of hard-bitten materialists to use the word “spiritual”. Why? There just isn’t, he says, any other word in English that has the same scattering of meanings.)

I also don’t mean that a science class should include the teachings of any particular religion. I’m not saying, for example, that it should be based in young-earth creationism, or Dianetics, astrology, or anything like that.

I.I.: I’m a Christian/Jew/Muslim/Buddhist/etc. Are you saying that your ideal science class WOULD be in tension with my faith?

Obviously, if your faith holds a non-mainstream view of the objective world, then it’ll be in tension with any mainstream science class — but that has nothing to do with Egan’s paradigm. (If, for example, you’re a follower of the traditional Buddhist notion that the Universe has no beginning, then the Big Bang is going to be at least a potential stumbling block.2)

I.I.: So you’re saying that young-earth creationist classes shouldn’t exist?

Nah, I’m addressing a different topic entirely. As a former young-earth creationist who discovered the joy of science through becoming convinced of evolution, I’m delighted to dialogue with young-earth creationists, but I’m not talking about how they should teach their classes.3

I.I.: What do you mean by “science should be spiritual”, then?

Let’s unpack that word.

2. What we talk about (when we talk about spirituality)

ChatGPT is probably a dangerous way to get answers to real spiritual questions, but let’s see how well it does when asked to unpack the meanings of “spiritual”4:

Self: achieving mental clarity & exploring your inner self

Morality: developing a moral framework and cultivating empathy

Others: participating in group rituals & connecting to your heritage

Purpose: asking the big questions & pursuing a meaningful life

Nature: revering the rest of the biosphere

The big picture: developing a cosmic perspective

God: believing in (and perhaps encountering) a deity/universal force

I.I.: How many of those does Egan education touch?

All except one (can you guess which?). But touching is easy — what’s interesting to me is how each of these seems central to an Egan education.

(1) Self: achieving mental clarity & exploring your inner self

We do kids a disservice, Egan writes, when we think that they need to start by understanding themselves. That’s foolishness. In reality, understanding ourselves is hard work; it only comes powerfully as we learn more about the rest of the world.

(2) Morality: developing a moral framework and cultivating empathy

Yes. While Egan argues that schools shouldn’t give a specific moral framework to kids, he does see morality as interwoven throughout the curriculum. We introduce children to potential heroes, and also help them ask questions about those heroes. We learn that empathy (cognitive, and emotional) can be given to villains.5

(3) Others: participating in group rituals & connecting to your heritage

Yes. To some extent this is implicit in all schooling, but it’s emphasized in Egan education. Kids gather together to hear stories, and become a community of inquiry who quarrel over ideas. And Egan sees “our heritage” as all the discoveries of people who’ve come before us. We learn to see mathematicians, scientists, and musicians as our kin.

(4) Purpose: asking the big questions & pursuing a meaningful life

Yes — as we lay out in PHILOSOPHY EVERYWHERE°, the big questions shouldn’t be held apart in a special subject, but should infuse all the school subjects, because they’re what gave birth to those subjects in the first place.

(5) Nature: revering the rest of the biosphere

Egan’s biggest contribution to science education might be his insistence that touching grass (and rubbing your face against rocks, and sticking your toes in swamp muck…) is as much a part of understanding the natural world as any equation you learned in high school chemistry. This is where reverence comes from.

He goes beyond this, suggesting that we imaginatively take the perspectives of animals in biology, and rocks in geology. My New Ager friends talk about “Mother Nature”, and my Catholic friends talk about “Sister Nature” — both fit modern science just fine. In the real world, everything is kin.

(7) The big picture: developing a cosmic perspective

Egan education is about understanding wholes more than any other educational theory I’ve found. Big history is an essential part of an Egan curriculum, as is getting an intuitive grasp of the size of the solar system, the galaxy, and the observable Universe.6

(8) God: believing in (and perhaps encountering) a deity/universal force

This is the one that Egan education has the least to do with. (Fellow Egan-heads might remember that Egan was raised a Catholic and became a novice in a Franciscan monastery in his teens, before losing his faith and become an atheist.7)

That said, the topic of belief in God has a more obvious place in an Egan education than in a mainstream education (or many other educational philosophies).

“The big questions”, in the West, have included an utter obsession with the existence of God. It’d be weird to specifically exclude this from the curriculum — so middle schoolers should consider, say, St. Anselm’s ontological argument or Al-Ghazali’s kalaam argument for the existence of God.8

I.I.: Oof I don’t like that.

Remember that considering doesn’t mean accepting, and counterarguments need to be included, too. In any case, there’s no need to be a purist: if these make you uncomfortable, and you’re the one calling the shots, you can always exclude them. (Though personally I’d challenge you to include ‘em because of that.)

But there’s probably a clearer way to look at all this.

3. The varieties of spiritual experience

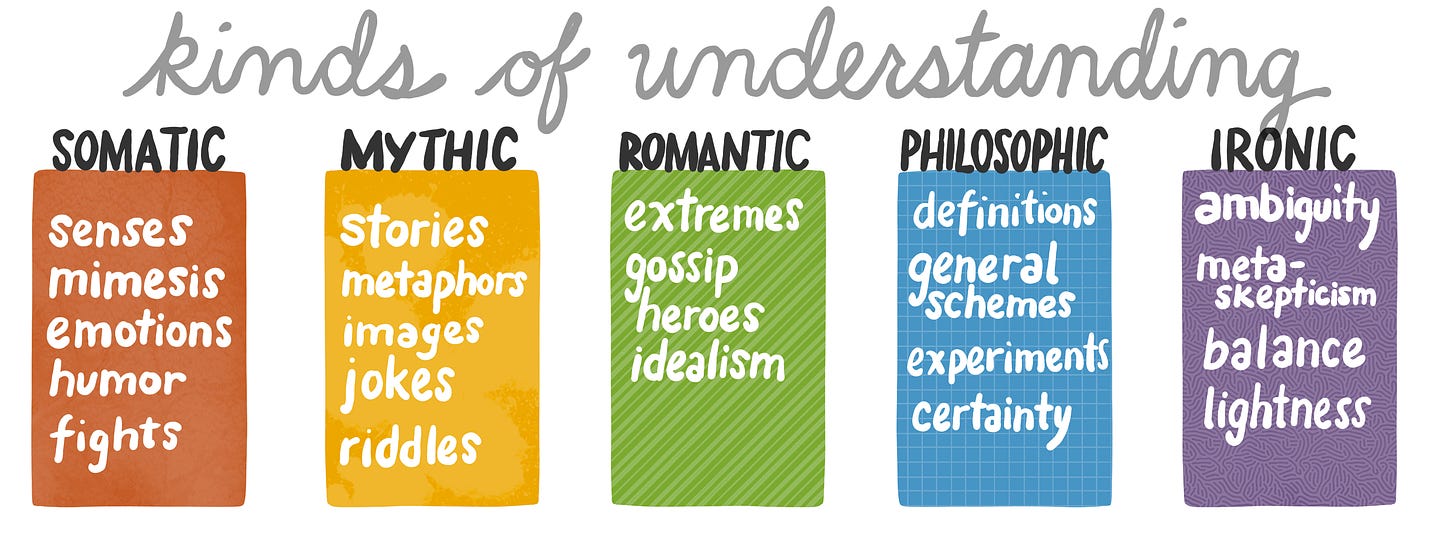

When we share images that try to capture Egan’s “kinds of understanding”, it’s easy to focus on the tools they contain:

But something’s lost in mistaking each as just a collection of tools. Each also has a flavor — a sort of stance toward reality that imbues everything with feeling. I think this is what Egan is talking about when he talks about spirituality. I’ll take a stab at sketching out how I see each of these coming into the science curriculum.

🤸♀️SOMATIC

We should help kids develop an embodied feeling of the things they’re studying. They shouldn’t just know names and formulas, but experience the textures and sounds and weights (and more) of nature. We should help them experience being raptly engaged in the world around them.

🧙♂️MYTHIC

We should help root kids in the tradition of the heroes who’ve figured out the things that we teach. For lack of a better word, we should discover gossip about them — their heroic virtues, villainous vices, and embarrassing escapades. We should also put kids in relationship with the world around them; inducting them into the names we use for different birds and trees and constellations and so on.

🦹♂️ROMANTIC

We should help kids realize, again and again, how weird everything in the world is. They should marvel at its extremes — the immensity of spaces between stars and galaxies, the tininess of the tiny animals that live on us, the age of the oldest plants, the speed of the fastest birds, the heat of lightning, and on and on.

👩🔬PHILOSOPHIC

We should help kids grasp the abstractions that hide behind what our senses show us. They should pursue the Truth-with-a-capital-T that was never designed to fit in our minds. These abstractions are often beautiful and sometimes frightening, but require study and sacrifice to achieve. While their joys may be austere, they can be as mind-expanding as any drug you can name.

😏IRONIC

We should help kids understand that at the cutting edge of science are scientists who look at the universe and proclaim we have no idea what’s going on here. Beyond our experiences, names, discoveries, and formulas are actual mysteries: what is it like to be a snail? what is cognition? why is there something rather than nothing? And can we even understand these things? The biologist J.B.S. Haldane put the ironic worry best — “The Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.”

I.I.: Tell us straight: how whacko would this sort of science teaching be?

Zero percent! Lots of great educators already do this stuff! The outdoor education folks, for example, do a lot of the SOMATIC (🤸♀️) experiential stuff. Anyone who writes popular histories of science (like Joy Hakim and Bill Bryson) does the MYTHIC (🧙♂️) gossip. ROMANTIC (🦹♂️) feelings are evoked by people like Carl Sagan and Neil deGrasse Tyson. PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) understanding is hit by every great high school and college science instructor (who often struggle to understand why their students don’t see how beautiful these abstractions are). IRONIC (😏) science is harder to find, but my favorite example of it is the book We Have No Idea: A Guide to the Unknown Universe by Jorge Cham and Daniel Whiteson.

This is all to say that pieces of what we’re doing are already in practice — it’s just that people don’t typically describe it as “spiritual”.

4. It’s reality, stupid

I’ll say one more thing that I’m playing with: maybe this sort of spirituality is all about reality.

I have a philosophically and religiously diverse set of friends, and what I maybe love most about them is that they care about reality. They may disagree over nearly every particular question, but they all want to (to quote a Catholic priest) “live as if the truth is true”.

Egan education flows from the twin notions that reality matters, and that it’s not as simple to access as we naively assume. We’re helping kids touch grass. Touch history. Touch history the cosmos. Touch reality.

Egan spirituality — whether we use that word or not — is all about connecting to what we think reality is.

So now the big question: should we use the word “spiritual”? My hunch is… well, I don’t want to bias the discussion in the comments, so I won’t say it here!

But I’d appreciate if you could take this quick poll…

…and then share your thoughts in the comments. If you find the word “spiritual” off-putting, what specific worries might you have? Any notions on how we can allay them? Any other words that you might recommend we think about using, either in its place, or in addition to it?

Page 193, for anyone who’s reading along at home.

Though my hunch is that many orthodox Hindu and Buddhist thinkers have already dealt with that; if anyone knows details, I’m eager to know ‘em. To the comments!

And in any case, the young-earth creationist movement is already using Egan’s tools far better than mainstream science; it’s how their movement thrives. Someday I should write a post about this; if you’d like to make that day come sooner, let me know in the comments.

I’ve edited its answer for brevity; if you explore this with a LLM and get very different answers, please let us know.

“Emotional empathy” means feeling what they’re feeling; “cognitive empathy” means understanding why they’re doing what they’re doing (as opposed to why people think they’re doing it).

As I lay out in one of Science is WEIRD’s first lessons, if you grew so big the Milky Way was just a tortilla, all the galaxies you could see would stretch out 30 miles in every direction, including up and down.

Though a Catholic atheist, as he’d frequently emphasize: much of his spiritual formation seems to have stuck. (He also wrote a book about Zen gardening. Probably that’s relevant here, too.)

The ontological argument: God is the greatest being that can be conceived; existing makes you greater than not existing; therefore, God must exist. The kalaam argument: everything that began to exist must have had a cause; the Universe began to exist; therefore, the Universe must have had a cause (and we can call that “God”).

If you can approach the world's complexities, both its glories and its horrors, with an attitude of humble curiosity, acknowledging that however deeply you have seen, you have only scratched the surface, you will find worlds within worlds, beauties you could not heretofore imagine, and your own mundane preoccupations will shrink to proper size, not all that important in the greater scheme of things. Keeping that awestruck vision of the world ready to hand while dealing with the demands of daily living is no easy exercise, but it is definitely worth the effort, for if you can stay centered , and engaged , you will find the hard choices easier, the right words will come to you when you need them, and you will indeed be a better person. That, I propose, is the secret to spirituality, and it has nothing at all to do with believing in an immortal soul.

Daniel C. Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon

I've been thinking about this for the last few days, and I'm a little dissatisfied with using the word spiritual based on a "scattering of meanings".

Most concepts, even if they're fuzzy, have a recognizable core. But from the list of seven things that you've defined as spiritual, it's not clear to me what exactly they have in common. What do these things share that makes us want to group them under the same label?

The one answer I can think of is that all seven are profound sources of meaning and purpose for most people. So perhaps instead of using a loaded word like "spiritual", it's better to say that education should provide people with a deeper understanding of what they consider the most important sources of meaning in their lives.