Previously, on The Lost Tools of Learning

We’ve been imagining an Egan education murder mystery: pretend it dies, and try to figure out whodunnit. Last week, I interrogated the first one of those. (Look forward to many more.) But as I read through everyone’s excellent answers, I found a more general fail state —

NOBODY MAKES AN EGAN SCHOOL IN THE FIRST PLACE,

because no one knows what it should LOOK like.

To be fair, the scenario didn’t actually allow for this answer — it presumed at least one school starts. But this might be our biggest potential problem.

Imaginary Interlocutor: Brandon, aren’t… you going to make one?

Ha ha, no!

Before our family moved to Minnesota, my wife and I actually did start an Egan microschool in our Seattle apartment. And it went… sorta awesomely. The whole story is one for another time, but one thing I learned in it:

Holy crap I should never be allowed to manage anything bigger than a loaf of bread.1

In any case, I’m fully committed to creating a six-year online Egan science curriculum — Science is WEIRD. And it turns out that creating life-changing interactive science lessons takes So. Much. Time. Which is all to say that, though I’ll be spending the rest of my life exploring the possibilities that Egan opens up, no one should be counting on me to actually start a school.

The most useful role for me to play, rather, is to translate Egan’s ideas into practices that others can run with.

And — as I look back at the history of this newsletter so far,2 I see that mostly, I’ve been yammering on about abstract educational theory.

Imaginary Interlocutor: So no more educational philosophy?

You can pry abstract theory from my cold, dead hands. I love it with a dark and desperate love — and know there’s an important role for it to play in getting Egan education into existence.

But: it’s time to kick off a new series: posts on how Egan can actually look in practice.

High or low?

Immediately, though, I run into a problem: should I write out high-altitude outlines of Egan education? Or should I glory in the ground-level examples of lessons?

So far, I’ve been jumping back and forth between these.

High-altitude stuff

I’ve already laid out some of the glorious content that Egan opens up. (A lot of this was in my ACX book review; see part 2 for elementary school, part 3 for middle school, and part 4 for high school.) Obviously the big curricular picture is necessary, but (as a number of you have brought up in the comments), it doesn’t help us understand what a classroom might look and feel like.

Ground-level stuff

“Your Solar System is Wrong” gave an example of what a single Egan-fueled lesson can do.3 And obviously some specific details are necessary, too! But there are too many specific details for any person to write. Worse, what we want is an archipelago of Egan education — Egan STEM schools, arts academies, vocational-tech institutes, and so on.4 What’s super helpful for one might be super useless for another. Ground-level is not an efficient way to spend limited time.

I.I.: Let me guess where this is heading — you want to focus on the middle level.

No, though that’s needed, too! We really need to focus on all the levels, and see how they all fit together and strengthen each other.

The question, of course, is how the heck we can do that. I’ve been pondering this, and I think I have the answer. And the inspiration for it comes from a 1977 book about (of all things) architecture.

A Pattern Language

When Christopher Alexander began, architecture was in a bad place.

His peers saw their profession as a branch of avant-garde art — the point of designing a building was to strike out boldly in a new aesthetic direction, to impress the critics, to provoke the normies! If a tortilla chip is a vehicle for salsa, then an architectural project (they held) was a vehicle for an idea.

Alexander saw this as trading a whole inheritance for a pot of stew. In his mind, the point of architecture was to understand how the built environment shaped how people lived, and to help them live better. A building was a vehicle for human flourishing.

Alexander was a Jew born in Austria; when he was two, Hitler annexed his country, and his family fled to England. He grew up in Oxford, the medieval city made of a mishmash of architectural styles: steep Tudor roofs, churches hugged by Gothic buttresses, industrial Victorian colleges walled with red brick, lofty museums built in imitation of the ancient Greeks, open squares popularized in the Georgian era, deep-porched houses built in the Arts and Crafts movement. Oxford was a city of no one design — it was an anarchy of styles. According to the au courant opinions of the architectural cognoscenti, it shouldn’t have worked. Yet, it was obviously gorgeous, and supported human life.

What did the people who built Oxford know that the architectural establishment had forgotten?

Alexander set the rest of his life to answering this question. Wanting to find the breadth of wisdom across the world, he traveled the world to see how different societies had dealt with the persistent problems of human living. And with his team, he wrote a book — A Pattern Language — to catalog the answers they found which popped up in culture and culture.

It wasn’t enough, he found, to describe mere buildings. A building is made up of rooms and staircases, windows and walls — each of which could make its own contributions to human life, or go wrong in its idiosyncratic way. And each building is a part of a street, a neighborhood, a city. To describe what they found, Alexander needed to show how buildings connected to higher and lower levels.

And so they invented a new kind of book. In place of chapters, they described 253 “patterns” — designs of any level of the built environment that promote human flourishing. They organized the patterns in order of descending scale, from towns to buildings to construction techniques. High-level patterns include things like “neighborhood boundaries” and “house clusters”; low-level patterns include things like “front door bench” and “paving with cracks between the stones”.5

Alexander & company knew, of course, that 253 patterns would be a bit much for most folks — a problem, as they were radicals of the charming 1970s sort. They wanted to empower people to design their own lives, and needed to make their book the sort of thing anyone could pick up and immediately start using. So they devised a standardized template for their patterns: the problem it solves, a description, diagrams, and links to other patterns that support it.

I.I.: You’re losing me.

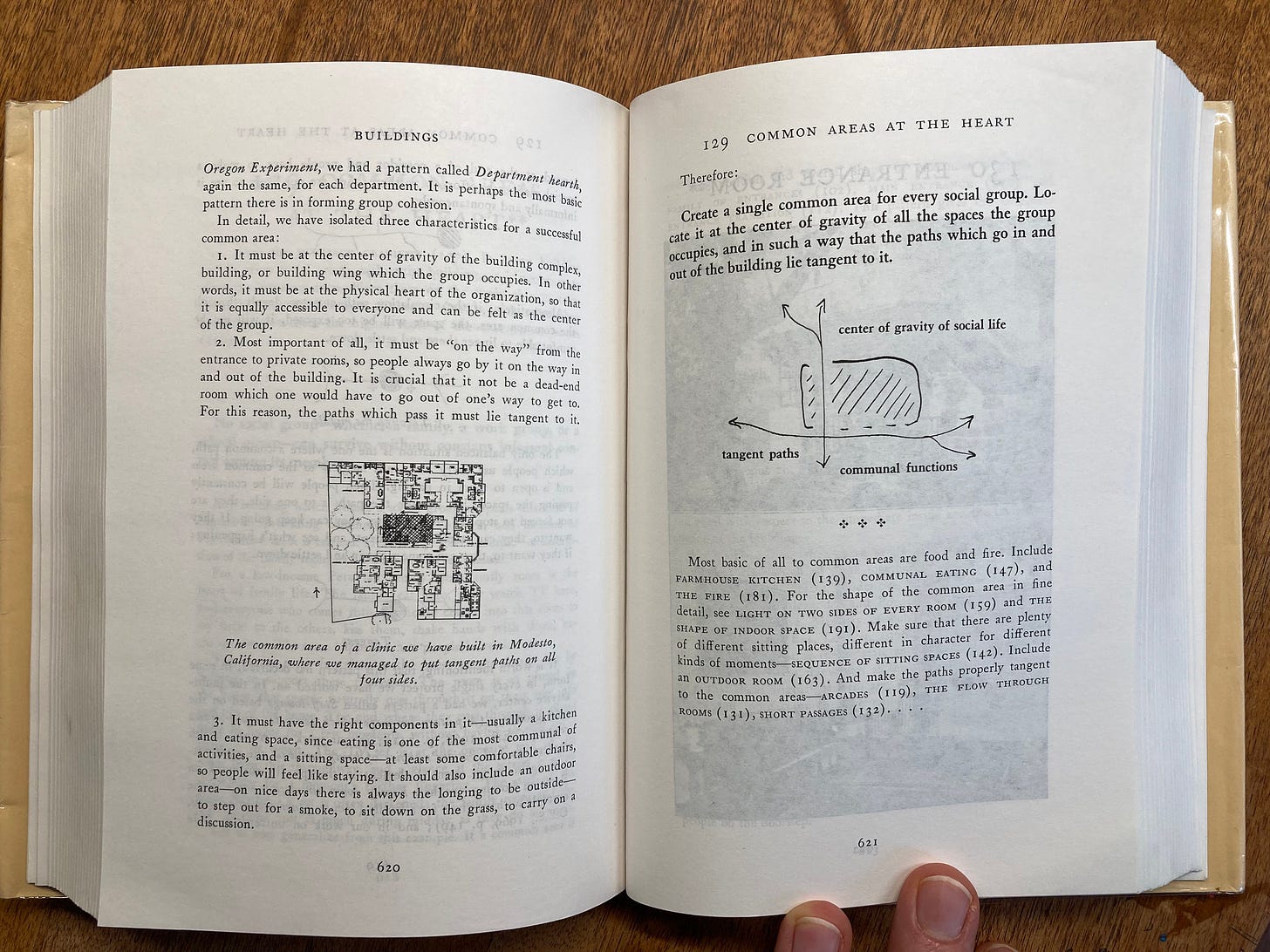

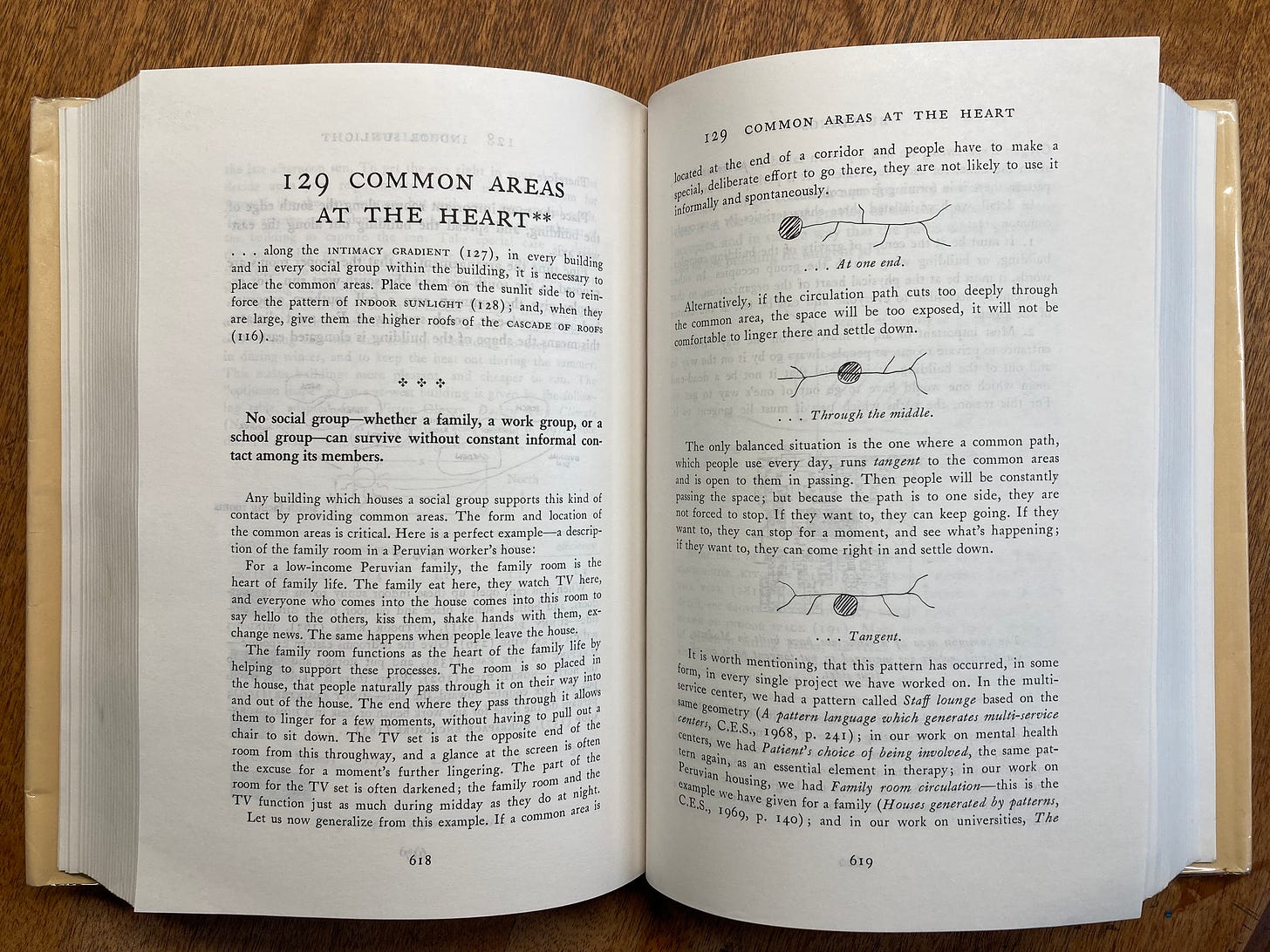

Here’s an example:

I.I.: I think I understand the “pattern” part. Why call it a “language”?

What they wanted was to spark a movement, and movements need common language. By giving specific names to the patterns they found, they hoped to make it easy for people to communicate with each other.

And it worked! To this day, Alexander has a devoted following in architecture (King Charles and Sarah Susanka of The Not So Big House series number among them). His ideas have spread even wider: if you’ve done Agile software development, played Simcity or The Sims, or used Wikipedia, you’ve dipped your toe into his intellectual lineage.

I.I.: Gotcha. Why are we talking about architecture, again?

Because — and here’s the big reveal! —

we’re going to start building

a pattern language for Egan education.

Christopher Alexander and Kieran Egan both grew up in the postwar British Isles. They both saw their professions to be chasing misguided goals. They both thought the mainstream intellectual world had lost track of the basics of human nature. They both found in the past the accumulated wisdom needed to help us navigate the future.

What else? They both settled down as university professors on the West Coast. They both attracted a devoted fan base.

Heck, they even both died last year, within two months of each other.

This is all to say: there are deep similarities between the two men, and between their approaches. I think the “pattern language” approach Alexander developed might be exactly what our nascent movement is looking for.

A pattern language for Egan education

I’ve prepared a bunch of patterns. Among them:

Public Speaking

Falling in Love with Books

Art Immersion

Math Megaboss Problems

Space-Repetition Shoebox

Learning in Depth

Question-Posing and Answer-Hunting

Cognitive Bias Spotting

World Religions

Site Grokking

Toaster Dissecting

Animals in the School

Big Spiral History

Drawing Maps

Epic Stories

Playing inside Stories

Dancing in the Classroom

A Poem a Week

Begin with the Whole World

People in Your Neighborhood

Intergenerational Conversation

Philosophy for Children

On Wednesday, I’ll start posting one (or so) a week.

I.I.: So you’re going to be ripping off Alexander’s approach?

And how! We will, however, be making a few tweaks.

Instead of organizing by space (towns/buildings/construction) I think we’ll organize by time (years/weeks/minutes). And we’ll be adding on a few new sections to the template of each pattern, to make it easy to discuss them.

Questions, answered

I.I.: Who are you thinking this’ll be useful for?

Middle-school language-arts instructors. Elementary school teachers. High-school gym coaches. Professors of computer science. Parents of preschoolers. Owners of jujitsu dojos. Autodidacts. Special ed teachers of all ages.

Which is to say: if you work with human beings — well then, probably, you.

There are two special sets of folk that I’m hoping this will be extra useful for: homeschoolers and potential school founders. These are the people who have the biggest blank canvases, who can reimagine education from the ground up.6

I.I.: Think there are a lot of homeschoolers who’d be interested in this?

Very much so! As a homeschool parent who literally wrote “homeschooling” into his vows,7 I can say that there’s a hunger out there for something that brings together the intellectual richness of classical education (without the rigidity), the emotional joy of unschooling (without the niggling fear that your child will grow up to be a mooch), and the glory of outdoor education (without, y’know, mud everywhere and all the time). I think something like this is what a lot of people mean when they say “eclectic”. Egan provides this, and more.

(Does that sound too easy? I became more confident of this when I was talking about my Egan workshops with the wonderful Cait Curley on her podcast The Homeschool Sisters — on, alas, an episode that’s yet to be released! She suggested her podcast pulls in many of the same folk who get excited by Egan, and that in fact there’s a whole contingent of the homeschooling community in particular who are dissatisfied with the options on offer — evidence of which can be seen in the many avowedly secular homeschoolers who are drawn toward the explicitly Christian approach of Charlotte Mason homeschooling.)8

I.I.: Are there oh-so-many “potential school founders” out there?

The streets are crowded with lovers;

there are thinkers on the subways.–Leon Wieseltier

Yes, there are. And some of them even know it.

Even before the pandemic, the microschool movement in the United States was picking up steam; in the last couple years, it seems to be going gangbusters. There are entire organizations (Prenda and Acton Academy come to mind) to guide ordinary folk through the boring nuts and bolts.

I.I.: Are you, Brandon, going to travel around the world to find these patterns?

If someone wants to front the money, I’m not opposed to it! But in a way, this is what Egan already did. He once described his method as just being an attempt to make sense of what he saw great teachers — across cultures, across ages — doing.

I’ve already prepared a bunch of patterns that I’ve been experimenting with over the last decade, but there’s room for so much more. Because — say it with me! —

Egan isn’t enough.

Some educational philosophies don’t play well with others, but one of the glories of Egan is that he helps make clear sense of what works across educational traditions. He throws open the doors so we can look into very different practices, and borrow elements that work. That means we can look into Montessori, Waldorf, and Reggio Emilia. It means we can consider classical Catholic schools, vocational apprenticeships, and Ayn Rand academies. It means we can take inspiration from Jewish Talmudic study, the Mandan Sioux training of young men, Siberian shamanic tutelage, Plato’s Academy, Aboriginal storytelling, Confucian exam schools, and Mesopotamian math riddling.9

I.I.: This sounds like a book. Is this going to be a book?

Wouldn’t that be amazing! Maybe. Sounds like a good Kickstarter project.

I.I.: You keep saying “us” and “we”. Is that just a rhetorical flourish, or…

This is too big for any one person to do.

I’ll propose patterns, and sketch them out. But the group of 1,000+ folk who’ve subscribed to this newsletter — yes, you — possess incredible knowledge. I want to tap into what y’all know, and use it to fill out this pattern language.

Which takes me to —

Wanna join in?

I’ve [grunting, followed by loud ‘thud’] turned on the “paid subscriber” option.

For $5/month (or — ooh, a discount! — $50/year), you can support building this by becoming a paid subscriber.

I.I.: Hmmmmmm… what’ll I get?

First, second, and third: my utter thanks, and once or twice a week the sweet tickle of realization “I helped with this”.

Like I’ve mentioned, my biggest challenge since starting this newsletter has been walling off time to write. At this point, there’s not so much left to cut out. I have three kids, and my wife has reacted quite stubbornly re: my proposals to set them free. Crafting killer science lessons takes a gargantuan amount of mental resources. And there are only so many reductions in habits like “walk around town with a friend loudly arguing religion” that one can make before one’s soul begins to shrivel. Lately, I’ve been contemplating nixing one of my favorite classes10 just to get more time.

I.I.: But how would my five bucks a month help you, then?

My wife and I are, at heart, miserly Norwegian farmers. We rarely buy frivolous things like “under-cabinet lighting” or “needed pairs of pants” unless we absolutely have to.11 This means that there’s a lot of low-hanging high-motivation fruit for us. Your $5/month will go into a special “HOLY CRAP YES!” account, and exclusively be used for stupid things that bring us joy when I publish posts on time.

I.I.: Let’s pretend I’m just a bit more self-serving than that. Any other perks?

Why, actually, yes!

Perky paid perks

I’ve thought long and hard through what I’m able to offer paid subscribers (thanks, Aaron, for your help in this). Paid subscribers will be able to…

#1 — Comment on “Pattern Language” posts

Each Wednesday (or so), you’ll get a new Egan pattern language post in your inbox. Well, we all will, but you’ll be able to comment on it! And they will be designed for commenting — looking for potential problems, for yes-and additions, for kinds of kids the patterns would be especially meaningful to. You’ll get to be part of a conversation that might have big effects on a lot of real people. Sometimes, when I particularly like an idea, I might bump it up to the main text itself, and give you props.)

#2 — Do a monthly-ish AMA

You’ll be able to ask me anything. (I mean, if it’s in bad taste, I probably won’t answer, but.)

Probable paid perks

I want to make sure I’m not overcommitting myself. But I also have in mind letting paid subscribers…

#3 — Participate in a monthly “book” club

There’s so much to talk about. There’s so much to talk about. So we’re going to try out a monthly book club. We’re all busy; these will rarely (if ever) be full books. More often, we’ll examine essays or chapters or podcast episodes that beautifully build ideas that have changed the way I understand education.

We’ll start with “A Mathematician’s Lament”, by Paul Lockhart (because it’s so good). After that, we might go to David Sloan Wilson’s “Learning from Mother Nature about Teaching our Children”, or we might do Egan’s “Learning in Depth”, or the multimedia essay “Animism is Normative Consciousness”. Or TanagraBeast’s “Seven Years of Spaced Repetition in the Classroom” over at LessWrong, or a chapter from Trivium 21c or the proposal for “Big Spiral History” I presented at the inaugural International Big History Association conference years ago.12

Once upon a time, I wanted to learn and discuss education’s most exciting ideas, so I enrolled in a master’s of education program at a well-ranked school. That ended up being a category mistake of epic proportions. I’m conceiving of this “book” club as the class on education that I always wanted to take. If you’re a learning science nutter like me… you might get a lot out of it. And for only $5 a month! Jeez! My inclination is to start doing these live as Zoom webinars, and experiment to see what works.

#4 — See hidden posts, who knows

Every once in a while something particularly spicy about education pops into my head, and I put it down on paper, and share it with friends.

Wanna… be my… friend?

(Oh that’s what the kids mean by “cringe”. Got it.)

I can’t promise I’ll actually write these (they’re spur-of-the-moment or nothing), but if I do, you can see it.

An extra level of support, move along, nothing to see here

$5/month × 12 months/year means $60 a year.13

If you look at that and think, BOY am I ever rich and here I am just throwing these Fabergé eggs at the wall and you’d like to give this movement even more help, WOW HAVE I MADE AN OPTION FOR YOU.

For the obscene amount of $800 a year, you can be a “Founding Member”.14 This comes with all the perks of being a regular paid subscriber, except (if you want) you can also do an hour-ish 1-on-1 phone/Zoom call with me, and/or commission a post — what would you like me to write about? (I’ll reserve the right to turn you down, but we can bat ideas back and forth.)

I don’t really expect anyone to choose this plan, so if you do, imagine my eyes bugging out for, like, 90 seconds right after I get the email. (Wait, did that just dissuade you? Eh. We aim for honesty, here; finances come second.)

Be our guest

Consider this an invitation to help re-imagine a core function of society.

I.I.: Brandon, I’m attached to my money, and I’m not choosing to give you it.

A perfectly fine choice! You’ll still get to read all the best stuff. And the greatest way to help with this revolution is to actually try some of Egan’s ideas out, spread them (when they work), and raise questions here (when they don’t).

Look, whenever I’m reminded that people actually read this newsletter, I’m floored. I spent 4+ months pressing my mind to a grindstone to write my ACX book review entry, and my only goal was to get to the semifinalist stage so lots of people would get to consider Egan’s ideas. That happened, and it’s continuing to happen. Your just being a reader of this puts me over the flipping moon.

I.I.: When’s the first pattern coming out?

Wednesday, with “A Song a Week”. Get ready.

If I started a normal-size school, within a month it would flood, catch fire, and fall into the depths of the Earth. The surviving faculty would become Mole-men and Mole-women. If I say I’m going to start a normal-size school, please conduct an intervention.

Not that long! Still time to become a completist!

Not coincidentally, it’s the one post that’s come out of one of my Science is WEIRD lessons. I see now that I’ve been doing my ground-level thinking about Egan’s there, and my high-altitude thinking here. Interestingly, that’s also my favorite post so far; “Your Thermometer is Wrong”, “Your Atom is Wrong”, and “Your Mushrooms are Wrong” are in the works. Someday. Someday…

You want more? Egan cosmetology institutes and flight training schools. Egan drug and alcohol rehab clinics. Egan online language learning software. Egan Hamburger Universities. Literal Egan clown colleges. I could do this all day.

footnote: A Pattern Language is thick and beautiful and expensive. If, however, you find this interesting, I’ll vouch that it’s easily worth the price of two or three or four ordinary good books. Shorter accounts of the patterns can be found online — here’s one list of them.

And keep reimagining it, if you’re homeschooling practice is anything like as haphazard as my family’s.

This is a lie, but it’s not far from the truth.

There’s a lot more to be said about this — expect a post on Egan’s and Mason’s [cue dramatic music] ABSTRACT EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES someday — but for the time being I’ll say that Charlotte Mason is the nearest thing I can point to for a boots-ready, Egan-adjacent approach to homeschooling. If anyone reading this is a serious practioner of Miss Mason’s method, contact me — I have questions!

There’s a subtle reference here — can you find it? — to Michael Strong’s most recent post “The Missing Institution: Why Our Young People Are Not Flourishing”, which is absolutely worth your investment. And for the record, any Bison skulls an Egan school would use would be wholly metaphorical, or at least antiseptic.

No, not one of the science ones — the one where kids do fight about Calvin and Hobbes to learn about the world.

One of the first things we bought with the ACX book review winnings was under-cabinet lighting, and it took me two whole months to find the time to install it, but I’ll say this: the hours of hunting for screws and screaming obscenities were worth it. Totally transforms the kitchen. Recommended.

Tanagrabeast: I’ve been following you for years, but I didn’t catch the ST:TNG reference until right now.

Well, twelve months a year now. If ha Moshiach comes and gives us the cajones to finally fix the Gregorian calendar with thirteen proper months of exactly four weeks each, I’ll lower the rate a bit.

I’ve never liked this title; it makes one imagine time, when really it should connote largess. I’m reading a new book about the years 1490–1530, and am reminded that it was the German Fugger family who funded, like, the whole modern period. Which is to say that I’m considering calling this category “Real Fuggers”. The first person to choose this category of support can decide to go along with this, or veto it.

An interesting parallel from my classroom experience is that most high school science teachers don’t seem to know what teaching the Next Generation Science Standards is supposed to look like in practice either. Pre-NGSS, in California at least, there were well-defined subject tests that covered the exact scope and sequence that teachers were expected to teach in order for their students to “succeed.” The day-to-day curriculum was more or less prescribed. Now with NGSS, the standards are vague and more skill-oriented. There is no feedback mechanism in the form of a standardized test at the end of the year to tell the teachers whether or not the students achieved the goals. There is also very little guidance on how to actually help the students acquire the targeted skills. Which is better? I don’t know. I think it really depends on the teacher. In my experience, teachers seem to fall into two broad categories: “just tell me what to do” and “don’t tell me what to do.” I wonder if one type would have more success in an Egan classroom than the other. Personally, I suspect it’s the second type that wants the control and freedom that would have more luck bringing his vision to life. It does seem like a pattern language would help both types though. “Don’t tell me what to to do” could look at the high-altitude, yearlong guidance while “Just tell me what to do” could use the ground-floor, minute-by-minute outlines. Homeschoolers will just continue to do whatever the heck we want, like always. 😂

I don't know if I'm the first but you got my 5 bucks. Well played, sir.