1. A problem

So much of the curriculum — in history, science, math, art, music, gym — borders on the profound. But in school, we flatten out profundities, reducing the curriculum to something that can give us right answers.

Meanwhile, you can occasionally find philosophy programs for young children, but they’re disconnected from the rest of what kids learn, cut off from the curriculum.

This situation is stupid.

2. Basic plan

When we study real content — and Egan education is all about this — students will naturally ask questions. Honor them by opening space for those questions. Have tools for capturing those questions, and norms for conversing about them. Be willing to put the rest of a lesson on hold to talk about the most important things.

3. What you might see

Little kids asking big questions — heck, big kids asking big questions, too! Earnest conversations about answers. Eyes going wide. Weird (and occasionally objectionable) answers being floated and experimented with. Kids going home eager to share what they’re thinking about with their family.

4. Why?

When we slice apart the subjects, they begin to lose their meaning. If we really want to revivify the curriculum, re-enchant the world, re-humanize education, we need to start connecting them back together.

The whole push toward “interdisciplinary learning” over the 20th century tried to connect them back together in various Frankenstein-ish ways: project-based learning, thematic units, integrated science and math…

And none of those are bad, necessarily. But they overlook the most obvious answer: that before scholars specialized, all the subjects were connected, and they were connected in philosophy.

5. Egan’s insight

Where do we see this in the human experience?

Have you ever played the “Getting to Philosophy” game on Wikipedia? Try this:

Go to literally any random page on Wikipedia

Read until you find the first link (ignore any links in parentheses)

Click that link

Repeat, repeat, repeat

You’re on the “Philosophy” page, baby!1

(No, seriously, try this. It’s unexpectedly thrilling.)

Imaginary Interlocutor: This some kind of Easter egg?

No, it’s what naturally happens when people bring knowledge together, and that’s because philosophy is the mother of all the disciplines. Once upon a time,2 philosophy was the only discipline. As thinkers specialized, they split off into their own communities.

First the mathematicians broke away. Then the physicists, then the doctors, then the astronomers. Heck, no one used the word “scientist” until the 1800s; before that, they were “natural philosophers”.

I.I.: But why does this matter to us?

The modern “let’s-make-learning-interdisciplinary” ways to reconnect the disciplines make a mistake — they try to connect the mature disciplines as they currently exist. And we shouldn’t exaggerate this — in the hands of gifted educators, “interdisciplinary learning” can be done well. But everyone agrees that it’s hard, and what’s not appreciated is that it’s hard precisely because those disciplines have spent the last centuries separating themselves from each other.

Once we acknowledge the history of the academic disciplines, it seems reasonable to look back to the beginning when they were all connected. And what do we see there? Philosophers — literal “lovers of wisdom” — asking the Big Questions, like

“What’s the right way to behave?”

“What is Man?”3

“What’s real?”

And kids are already asking the Big Questions!

“Is it okay to lie?”

“Are we animals?”

“Where did the Big Bang come from, anyway? (and are we living in a video game?)”

The disciplines we’ve built schooling around — math, science, history, and so on — arose precisely to help answer questions like this.

Bringing in philosophy allows us to connect the subjects together naturally, in a way that presses the “meaning button” inside of kids’ minds.

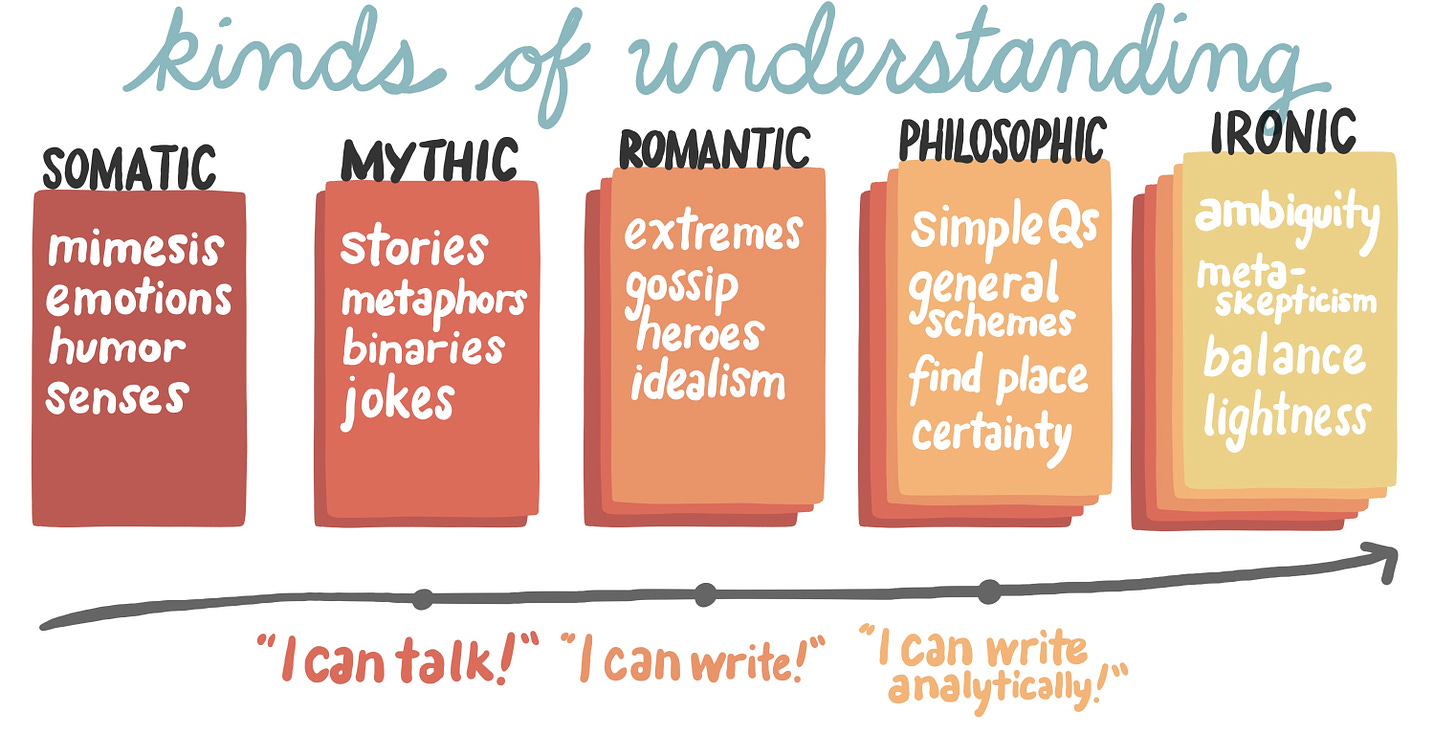

How might this build different kinds of understanding?

It’s easy to misunderstand Egan’s framework —

— as saying that we should hold off on doing PHILOSOPHIC (👩🔬) stuff until kids are older. (What do these weird emoji mean?)

Nope, nope! The opposite!

The goal of an Egan education is to max out every way of understanding the world; among other things, that means we should be very conscious of how we encourage PHILOSOPHIC understanding early.

And this — leaning into kids’ natural asking of 👩🔬SIMPLE QUESTIONS — seems like one of the most powerful, and easiest.

6. This might be especially useful for…

Kids who will find little value in school until the big questions are addressed.

7. Critical questions

Q: Will teachers feel comfortable with this?

Some teachers will love this — for a lot of us, this is why we got into teaching in the first place.

Q: Won’t this touch on some of the very most sensitive questions that people ask BY DEFINITION? Isn’t this a recipe for disaster in a classroom?

It’s a recipe for setting an environment of respect and inclusion.

Q: I’m imagining an 11-year-old going home pondering her mortality, crying herself to sleep, and the parents calling the school irate.

A couple things.

First, wearing my dad hat, I want to say that our kids will inevitably feel scared by existential questions. And frankly, I’d prefer that they first meet these questions in a classroom — you want your kid learning about Nietzsche in school, or on the street?4

Second, an OT friend points out that when kids recognize that a classroom is a place where they can talk through these uncomfortable ideas, those ideas won’t be as scary!

I’m hungry for any thoughts y’all have on this.

This is a pretty big pattern — can you think of another way this could go terribly, terribly wrong? Our guess: yes, yes you can. And we want to know about it. Become a paid subscriber and join in the (fairly active) comments conversation.

8. Classroom setup

—

9. Who else is doing this?

Loads of people. The Philosophy for Children (cool people refer to it as “p4c”) movement was started by Matthew Lipman in the 1970s; in the fifty years since, it’s blossomed and diversified. Groups include the Philosophy Learning And Teaching Organization5 in the US and the Society for the Advancement of Philosophical Enquiry and Reflection in Education6 in the UK.

And loads of people have written loads of books. I’ll admit that I’ve never read any of the classics (Garreth Matthews’ The Philosophy of Childhood is perpetually cited), but I enjoyed the recent Nasty, Brutish, and Short: Adventures in Philosophy with My Kids by Scott Hershovitz.7

I’d be negligent if I didn’t also point to the work of Michael Strong, author of The Habit of Thought: From Socratic Seminars to Socratic Practice (and friend of the blog!). He runs The Socratic Experience, an online Montessori-inspired school that has kids engaged in Socratic discussion for two to four hours a day. (I’ll just say that my wife and I are looking at it for our middle-school age daughter.)

And all this is just scratching the surface. Our hope is to draw from all this stuff as we find it useful, and (once again) give it more juice by connecting it to our intellectually rich curriculum.

How might we start small, now?

Tonight at dinner, ask your kid if it’s ever okay to lie.

10. Related patterns

Philosophy Everywhere° is one way to encourage students to connect what they’re learning; teaching Big History° and telling the Epic Stories° of math and science and whatnot is another.

We can prompt some of the biggest questions by including World Religions Throughout° (July 12) the curriculum, starting even in elementary school. Some questions — like Where do We Come from?°, What Are We?°, What is the Good Life?°, and What is a Good Society?° — are so juicy that we’ll want to consciously build them into the curriculum.

Practices like Question Boards° and Cheese, Wine, & Posters° can make it easier to focus time and attention on the questions kids are asking.

Students won’t stop considering these topics when they get home, and we can invite Intergenerational Conversations° about them.

Afterword: Going full-meta, here

Y’know, host Jeff Young asked me “how does an Egan classroom look different?” on the EdSurge podcast last week, and I had a hard time answering that. And in this pattern, too, I noted that there’s little to write in the “Classroom Setup” section.

This morning, I realized that there’s something important here — that for Egan, the problem with school is less what kids are experiencing externally with their bodies (though there’s lots of room for improvement there) than what they’re doing with their minds.

Next time I’m asked how an Egan classroom might look different, I might responsibly channel how I think Egan might reply and say:

Holy $#*& we’ve gutted the curriculum of everything that matters, and you want to talk about what the CLASSROOM looks like???

And I think that putting philosophy back in — and understanding that the whole purpose of academics was, originally, to “love wisdom” — is actually pretty central to this.

To be fair, this doesn’t work 3% of the time — there are occasional loops you’ll get stuck in. As Puck says in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “The course of true crowdsourcing never did run smooth”.

In 586 BCE, on October 8, when Thales was so intent on watching the stars that he fell into a well.

Pronounce this one portentously.

Do kids even go in the street anymore? Replace that with “on YouTube”, maybe. [sigh]

Get it?

What we’re learning here is that philosophers love wisdom and acronyms.

He has a good interview on the Freakonomics podcast. Unrelated — when I look up “Philosophy for Children” on Amazon, I get a paid suggestion for The Boy, the Mole, the Fox, and the Horse. I should probably write a post on this someday, but I’ll stir up trouble here by noting: I despise this book.

YES YES YES! The elephant in the room here is our deteriorating ability to engage in civil dialogue. Philosophy is dangerous... It opens up possibility! And sheds light on different ways of thinking. I say there is a connection between us playing it safe in our classrooms and communities and the political messes we are in. Could someone research how the mandatory TWO philosophy courses in high school (and ethics in lower secondary) in Finland are adding to the kind of political climate that allowed for the incredibly civil presidential election there between 9 candidates last week, each of the candidates being a fine option?

Strongly second all this! One funny invitation into this in our house came from "Let it Go" (our girls haven't see _Frozen_ but they know the song).

My 4yo was very confused by Elsa claiming "no right, no wrong; no rules for me. I'm free!" Didn't that make her a Bad Guy?