Could Egan’s paradigm help kids actually learn a second language?

With the sixty families of the Skeleton Army, I’ve been working on a new approach to homeschooling (Egan homeschooling). This summer I’ll be presenting what we’ve come up with as a series of workshops. But one of the hardest sections has, predictably, been how to teach your kids a foreign language so that they actually speak it.

If we can pull this off, we can demonstrate to the world that Egan education is powerful for learning things that are terribly hard. If.

Wanna give us some help? Read our current thoughts on how to do this, and give your thoughts in the comments. Include your own personal experience and qualifications (e.g. “I’m a linguist and polyglot who speaks eight languages fluently, and also have just deciphered Linear-A”, or “I have attempted and failed to learn two languages in college, but remember the German I learned playing Wolfenstein 3D”).

Imaginary Interlocutor: Brandon, what’s your authority for writing this?

None at all. I did two semesters of German, and four of modern Hebrew, and remember absolutely nothing. (Though you should see my Wolfenstein 3D completion times!) I’m a failure in learning languages… which makes me like a lot of other people. I am, however, very frustrated by this, which has led me to read a lot of cognitive science about language acquisition.

I.I.: You say that schools fail to teach foreign languages, but, like, lots of people around the world speak pretty good English.

This is something I’d like to understand better — please share anything you know about this in the comments. My experiences are mostly American, where we grandly usher students into the hallowed halls of language learning, and then ignore it when 99% of them trip and fall down the staircase. Virtually no Americans who study a foreign language in high school actually learn to speak it.

I.I.: But who cares? AI translation is getting better and better; we’re moving pretty quickly to the “universal translator” of Star Trek.

A lot has been written about the values of learning another language; I’ll mostly avoid that in this post, though in the summer workshops (and the book that’ll follow), I’d like to include some choice reasons to learn one. If you have any ideas, throw ‘em into the comments!

I’ll only add here that trying to learn a language and failing is worse than not doing anything at all. It sucks up time, and leaves you with the niggling sense that “I just must be bad at learning languages”, when the real problem is the method you’ve been given.

I.I.: But isn’t this a solved problem? Just immerse yourself in the language. Make friends with people who speak it, move to the area, and so on.

I think this is more-or-less true, but devilishly hard for most of us to actually do. We’re looking to create a method that doesn’t require immersion.

I.I.: Aren’t there apps that do this? Why reinvent the wheel?

My sense of this is that some apps — perhaps especially Fluent Forever? — really have solved the problem. The only trouble is that they require (1) a competent adult with (2) a lot of motivation. Most elementary-age kids (my sense is) aren’t likely to be able to sit down and use these apps as often as they’d need to. So the goal of this is to create a set of practices by which a whole family can become the sort of linguistically-competent, highly-motivated people who can rocket through an app, and come out the other side knowing the language.

(If that sounds like a rather small goal, that’s okay with me, but I think this’ll still be hard.)

I.I.: What are you drawing from, as you craft this approach?

The paradigm of Kieran Egan, and the mechanics outlined beautifully in the book Fluent Forever, by Gabriel Wyner. I’m focusing on this book because

it explains the science of learning so well that I recommend it to people who want to learn cognitive psychology (even if they aren’t interested in language)

it’s connected to a website (fluent-forever.com) that are rich in videos and free downloadable resources

there’s an app! (Back in 2017, it broke Kickstarter’s funding records for language-learning software)

it’s short and punchy and hilarious and OMG THERE’S A NEW EDITION OUT

Frankly, I’m in love with Wyner’s approach — and I haven’t even used his app yet. If anyone knows any spicy critiques of it, or whether it doesn’t live up to its promises, I’d like to know. Much of what’s below is an attempt to Eganize it… though there are already quite a few Egan elements of it already.

I.I.: What does Egan have to add to this?

Like I said, with enough motivation, any competent adult-like-person can learn a second language… but oof it takes a lot of motivation. Eganism thrives on increasing motivation — and not by spooning it on (what we in the ed biz call “chocolate on broccoli”) but by bringing out what’s already captivating and marvelous inside the material itself.

Because, my goodness, language is fascinating.

I.I.: But will this method work?

Not yet, no.

This is a work in progress; I’m posting it here to get your advice. But I won’t be humble — the goal of this is to create a path toward learning a new language that the majority of homeschooled kids (and, eventually, kids in school) can use that will actually result in their speaking another language.

I’ve broken this into five pieces — help your kids taste “language”, adopt a language as a family, tune your tongue, eat a thousand words, and chew on phrases. In this post, I’ll cover the first three.

1: Taste this thing called “language”

If you grow up in a monolingual community, it’s easy to take language for granted. Our native language quickly becomes second-nature to us, and we only see its weirdness when we’re around other, impenetrable languages — especially ones that sound so very different than our own.

And, dang it, language is weird. By vibrating our food holes and whipping around our mouth-tentacle, we trigger specific patterns of neurons in each other’s heads. It’s nigh-miraculous (if a bit gross).

So what we want to do with our kids is to introduce the very concept of language, to help them see that language is a thing distinct from themselves. We don’t want to do so “academically” but MYTHICALLY (🧙♂️), by introducing kids to a sense of (dare I say?) magic.

Alessandro’s idea for this is to simply take something in the house — a pencil, perhaps, or a pet — and start saying its name in another language.1 A 🐕 is not a “dog” — it’s a perro, a sobaka, a gǒu, a kalb, a mbwa, a köpek, an inu, a koira, and a chichi.2 The words we call things aren’t interchangeable with the things themselves; they’re quite random.

What you can do here is to pick some of your kids favorite things, and look up the 🧙♂️NAMES for them in different languages. The effect you’re trying to trigger is a sense of confusion and wonder, and (ideally) a feeling that words are somewhat magical — they’re arbitrary mouth movements that allow us to point to things in the world.

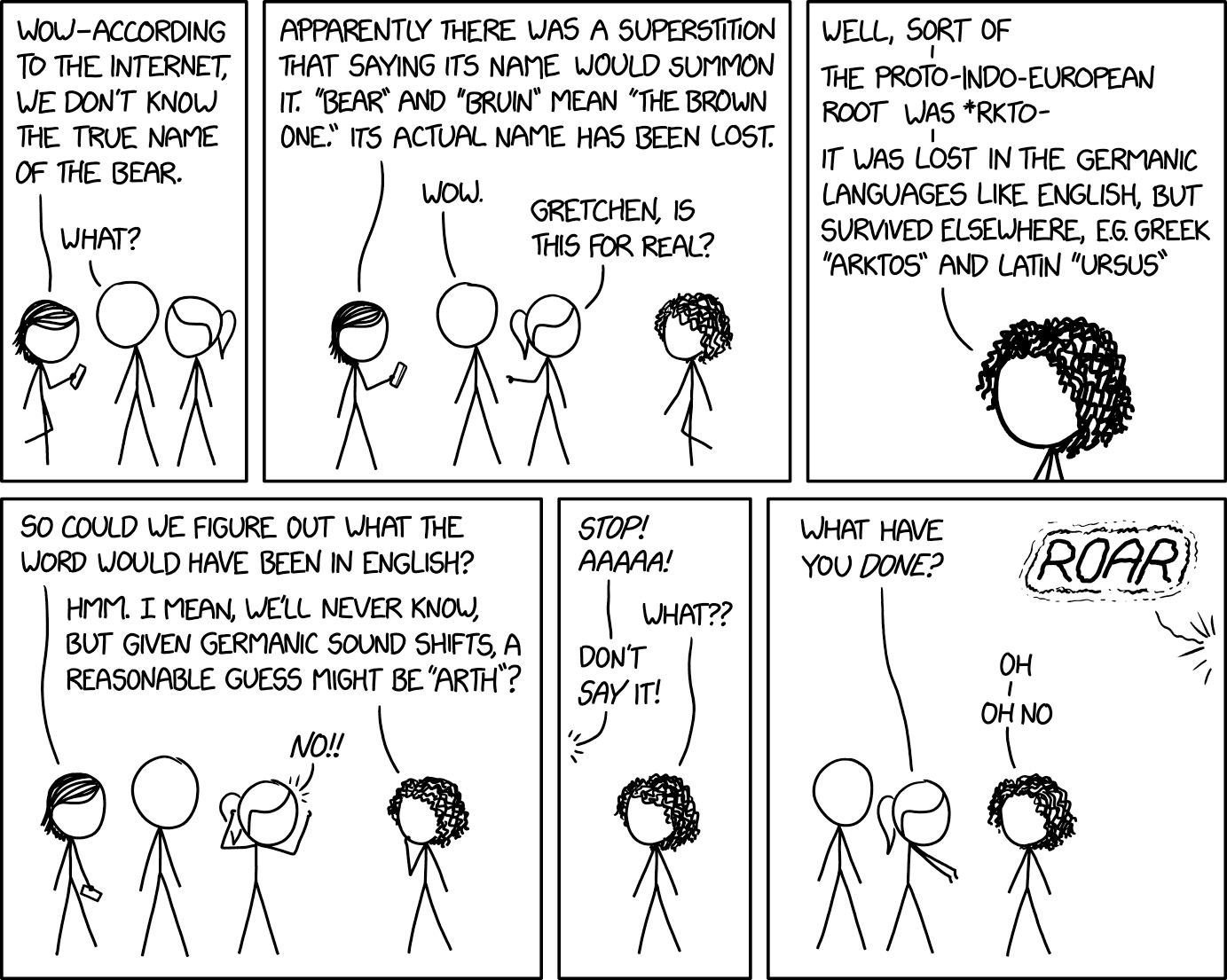

Note: are there any better ways we can do this? Perhaps we can tell them 🧙♂️STORIES showing that, to many oral-language tribes, words are understood to have power. The Germanic peoples feared that saying the true name of the bear would alert it to your presence, and so substituted the phrase “the brown one” instead.

Others — Ursula Le Guin made this famous — believed that saying someone’s name gave you control of it, so they guarded their true name and only told others their nickname.

I still feel like we’re scratching the surface with this one. If you have other ideas for how we can communicate this sense of the magic of words to kids, let us know in the comments!

2: Adopt a language (as a family)

It takes a village to raise a child speak a language.

Noam Chomsky aside, the purpose of a language is to allow you to communicate with others. And yet many people learn languages on their own. They practice with an app, not with other people. Even those who go to classes don’t do much speaking to other students in the language.

To tap into the power of speaking a language to others, we’re going to have your whole family learn the language together.

I.I.: Which language should our family choose?

Educational progressivists usually urge you to choose the most useful language (in America, this is often held to be either Spanish or Mandarin; in much of the rest of the world, it’s English), and educational traditionalists urge you to choose the one that’s most important (Latin! it’s always Latin, to them). You can go with either of those — but you can choose entirely selfishly.

which language might help you talk to people you love?

which one is associated with your favorite restaurants?

which one sounds the most wonderful?

which one is from a place you might like to visit?

That last one is important, because as part of adopting a language, you’re also going to set a time on the calendar in a few years to go on a family trip to where it’s spoken.

I.I.: Why is it so important to plan a trip now?

Learning is an adventure, and a hard one. That might be Kieran Egan’s central insight, and since language is so hard, you want to plan in the exciting part at the very beginning. This gives a purpose to learning your language — you want to be able to interact with people in another culture, and have an amazing time. This is going to gin up motivation, which will naturally fluctuate.

I.I.: Does everyone have the money for this?

You can, of course, skip this — but if the whole family makes a project of saving the money over the years, you probably can make it work.

Preparing to go on the trip will become an important piece of your homeschooling. Beyond learning the language, you’ll be learning about the culture, the geography, and the history of the place. So if you’re short on money, you might not want to pick a language that’s only spoken someplace it’s pricey to get to.

I.I.: Any other considerations for choosing the language?

How long will it take to learn?

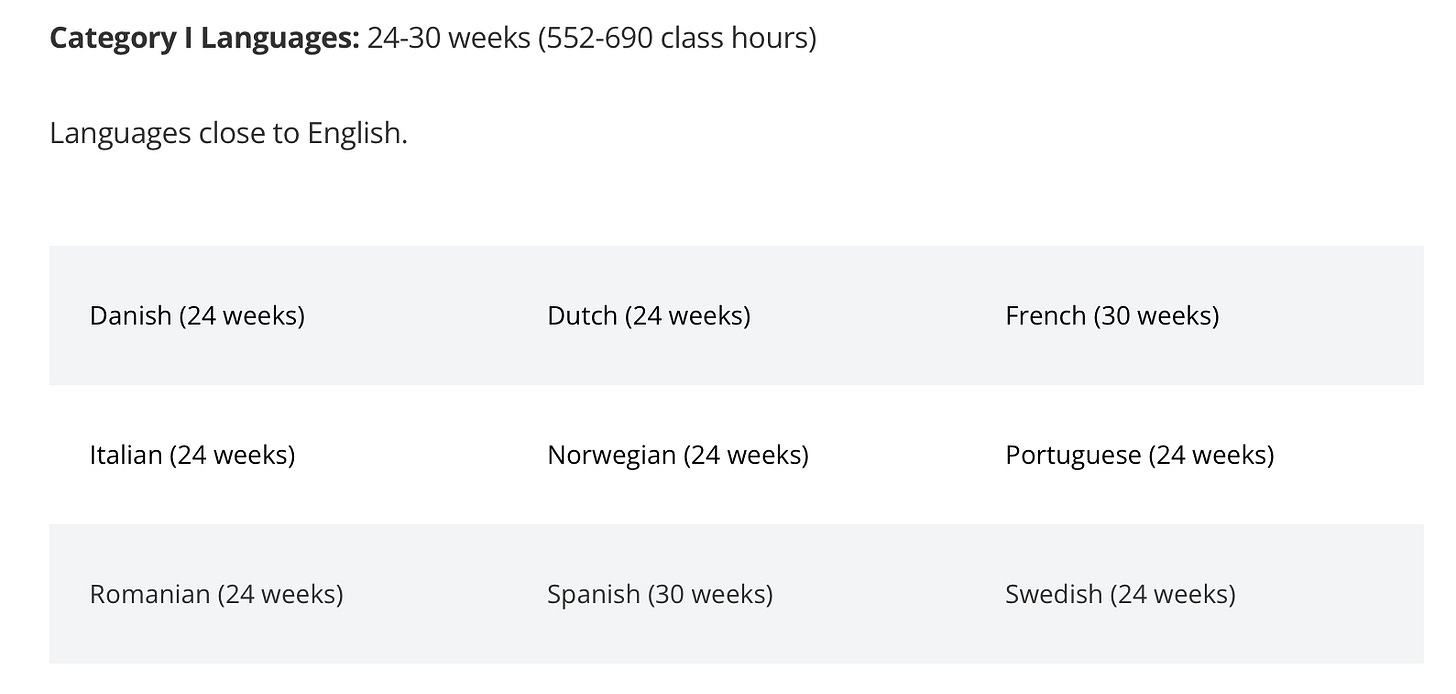

Some languages are harder to learn than others, depending on what languages you already know. The US State Department puts languages into four categories. They’ve found that those in Category I are, for most people, the easiest to learn, and take about 1,200 hours (600 hours of class time and 600 hours of self-study) to get to a professional working proficiency:

Categories II takes longer (about 1,600 total hours) and III takes longer still (about 2,000 hours); those in Category IV (Arabic, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean) are said to take around 4,000 hours.

I.I.: Will we be able to spend enough time on this?

If we’re making a method that will actually work, we need to make sure we can. So let’s make some assumptions:

you’ll be homeschooling around 180 a year

you’ll spend about 1/2 hour a day on this from grades 1–4 (what we’re calling “elementary school”)

180 days × 1/2 hour a day × 4 years = 360 hoursAt this rate, by fourth grade you won’t even be close to the ~1,200 hours needed to learn a “Category I” language. But if in middle school you plan to double the daily investment of time —

180 days × 1 hour a day × 4 years = 720 hoursyou’ll (naturally) get twice as much.

And if you add the two, you get —

360 hours in elementary school + 720 hours in middle school = 1,080 hours…dang close to the target of 1,200 hours for a Category I language.

At first blush, at least, this seems like enough to be able to speak a Category I language by the end of eighth grade. And if you want to adopt a Category II or III language, you can just plan to continue through to high school.

(If your family wants to tackle a Category IV language, you should plan to spend a good deal more time on it.)

I.I.: Any other practical considerations?

Which languages have the best resources? Obviously, they can expedite your learning, and Portuguese (spoken by a quarter billion people) has better resources than, say, Pirahã (pronounced PEED-uh-han, spoken by less than four hundred people in the Amazon).

3: Tune your tongues

A major problem is that other languages are built out of sounds that you’ve forgotten how to make.

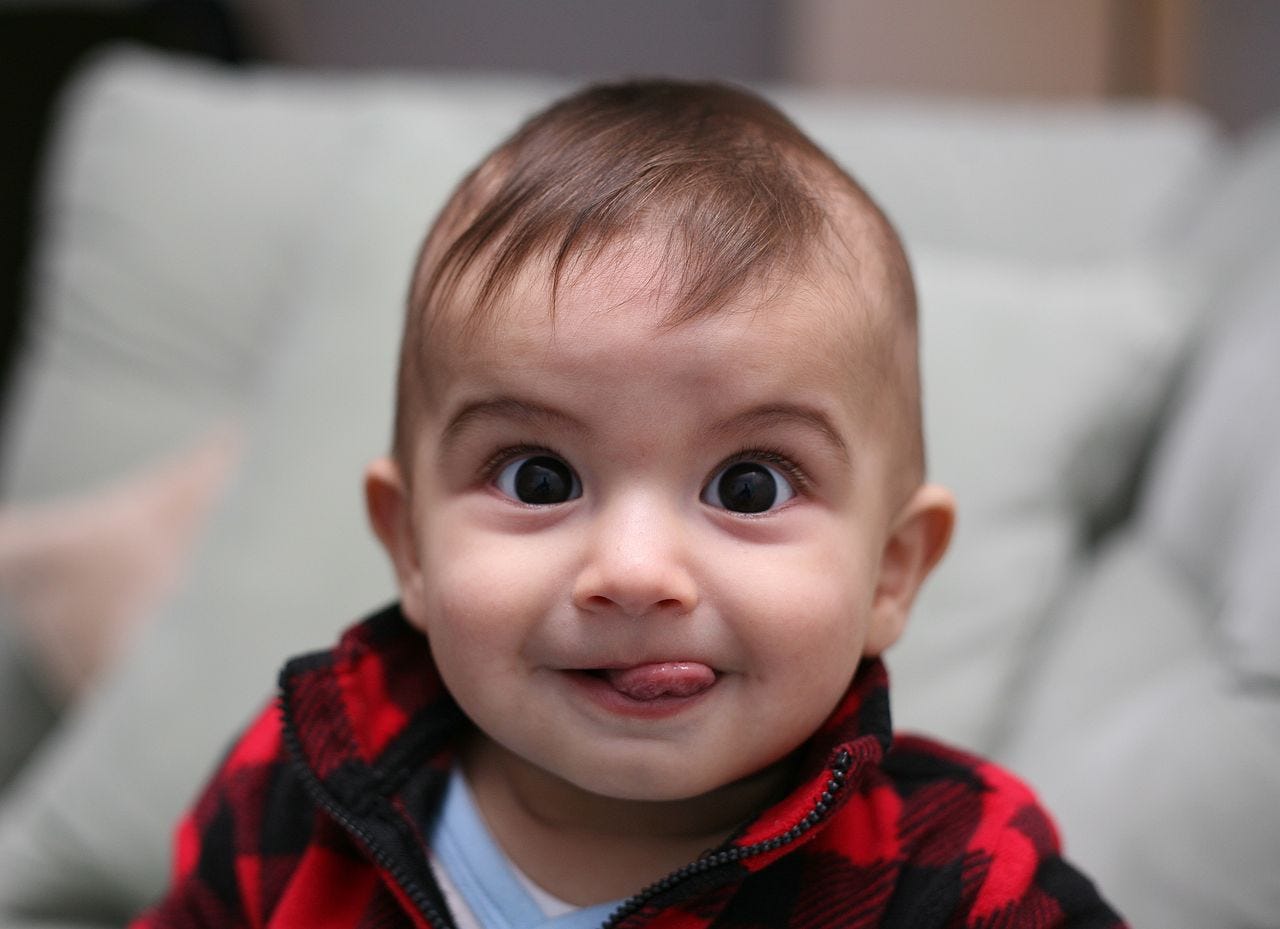

Humans are able to make about at least 300 different consonant sounds, and at least 100 different vowels, and when you were a baby, you babbled all of them.

And then you forgot how. You imitated (per Egan, 🤸♀️IMITATION is the SOMATIC tool par excellence) the people you heard around you, and directed your tongue to focus on only a handful of positions.

Depending on the dialect, English has around 40 meaningful sounds,3 and Japanese has only 20… but four or five of them don’t appear in English at all. (The Japanese “r” sound /ɾ/, for example, is between the English “r” /ɹ/ and the English “l” /l/.) So one of the very first things you’re going to do is learn to make all the sounds of the language you’re adopting — and then teach your kids to do the same.

I.I.: How the heck are we going to do that?

You need to…

learn to write the sounds

learn to hear the sounds, and

learn to make the sounds.

This is all finicky and hard — but I think it’s a solved problem. Wyner explains the theory behind this in chapter 3 of Fluent Forever, and has expanded on that with free videos on his website.

I.I.: This seems like a lot of work to have to do first. Why not start by learning vocabulary, and then work on pronunciation?

That is the normal order to do things in, yes. The trouble is, it’s probably stupid.

Our ultimate goal is to speak another language naturally. We don’t want to have to pause and think about how we’re pronouncing it, we want it to be a transparent medium to express what’s in our minds. Learning how to say words wrong means that you’ll have to go back and unlearn them — you’re not saving yourself work!

I.I.: What’s so wrong with speaking with an accent?

Nothing! (And here I have to remind all my friends who speak accented English as a second, third, or tenth language that you are so much better than me.) But speaking with a perfect accent is a way to tell native speakers that you respect the heck out of their culture even when you’re still struggling with the vocabulary and grammar. It’ll nudge some people into wanting to give you guidance when you go astray (which may prove crucial). It also might give you more confidence.

Anyhoo, if I’m right that “train your tongue” is a solved problem, our job needs to be figuring out how to teach this to our young kids — and not just teach it, but to make it feel vital by bringing out what’s most wonderful in it.

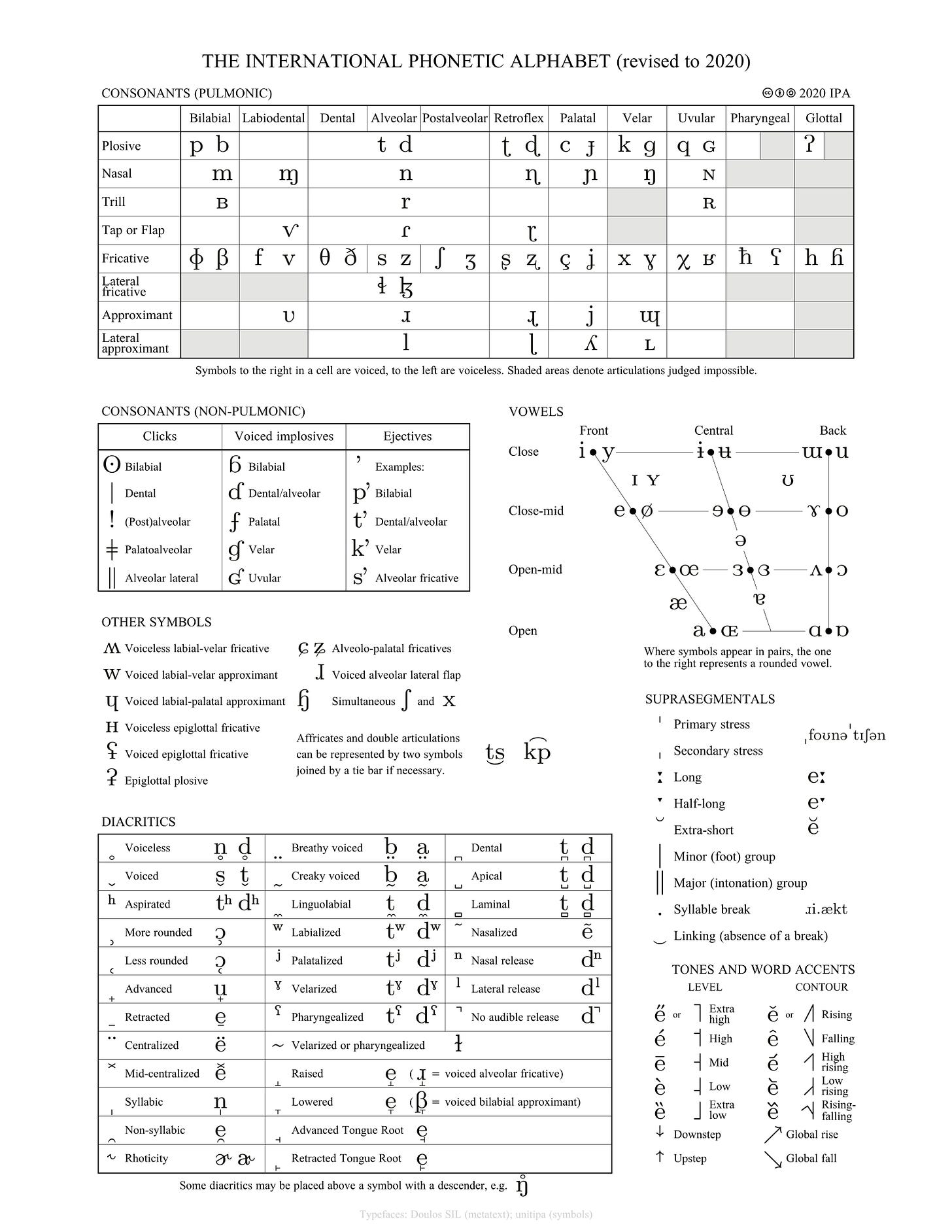

In a word, we need to Eganize it. And, for writing the sounds of our adopted language, that means using the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Learn to write the sounds

I.I.: How can we Eganize the International Ph*&ing Alphabet?

Alessandro and I have talked about this, and have come up with two ideas. None of them has been field-tested yet, so take these as ideas to play with.

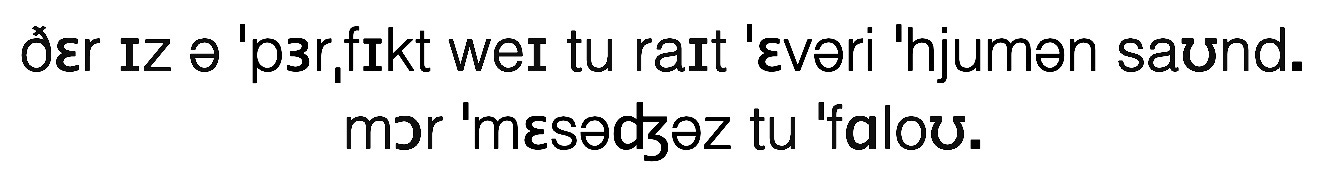

The first is to introduce the IPA through and 🦹♂️CIPHERS. Imagine being your kid, coming out for breakfast in the morning, and finding a secret message posted on the wall:

You’re bewildered. This isn’t English, is it? But some of the words look familiar — “ɪz” looks like “is”, “hjumən” looks like “human”. You try to sound it out aloud, and mostly fail. But you can’t ignore it. Throughout the day, you try it again, until you figure it out. Huzzah!

Now, as the parent, each day put up another message for them to try out. (There are websites that will transliterate English to IPA, which is where I made the above from.) Don’t insist that they decipher it. Unless they demand it, don’t give them a key. Draw out the mystery of phonetics. (Long-time readers will note that this is a variant of the pattern MYSTERIOUS MESSAGES°, which may be worth re-reading here.)

The second is to help kids like the IPA through a 🧙♂️STORY. Beneath the cold, confusing exterior, the IPA is the miraculous creation of a team of obsessives who wanted to know what sounds humans made. To catch the excitement, watch some YouTube videos by other language geeks — start with Xidnaf’s, then do Tom Scott’s, then do CrashCourse’s videos on consonants and vowels.

You can either tell the simple, two-sentence version of this, or you can have your kids watch one of the videos. In any case, after they’ve heard the story, unveil the IPA chart. Build up how terrifying it looks. (“Many men have looked upon this, and gone mad” might be a fun way to characterize it. Probably true, too.)

Learn to hear and make the sounds

This is harder than you might think.

Again, when you were a baby, you babbled in all the possible sounds human languages use. (This babble is part of the biological foundation of language; it’s what different languages draw from.) The trouble is that as we age, we don’t just lose the easy ability to make most of those sounds, we also lose the ability to hear those sounds.

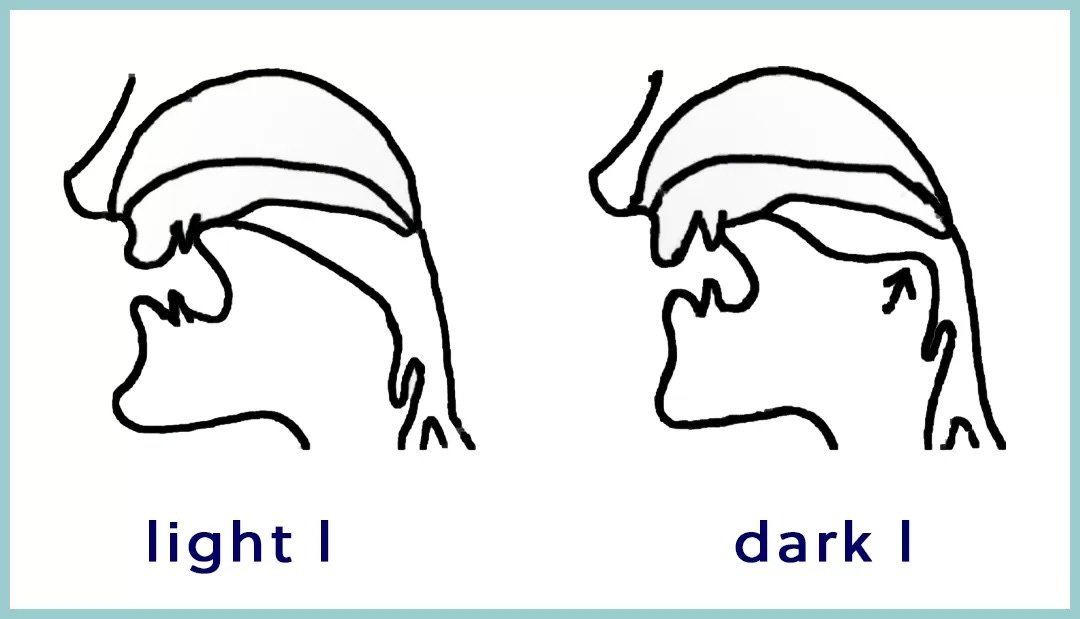

You might have already heard of how Japanese conflates /r/ and /l/, but did you know that English conflates /l/ and /ɫ/?

/l/ (called “light L”) is the sound we make in English when a word begins with the letter L: “leap” and “luck” and “loop”. /ɫ/ (called “dark L”) is the sound we make when a word ends with L: “pal” and “mull” and “gel”. When you make it, you raise the back of your tongue a little:

In English, we make both of these sounds, but they don’t mean anything to us. But they do in Lithuanian. In Lithuanian, /l/ and /ɫ/ can appear anywhere in a word — beginning, middle, or end. And if you put in the wrong one, people will you at you oddly. In order to learn Lithuanian, you need to hear the distinction between these sounds.

Most of the new sounds you need to learn are like this — not “entirely novel mouth movements” but “sounds I’m already making but not paying attention to”. So before you can start making your language’s sounds, you need to train yourself to distinguish these.

I.I.: How can we Eganize that for our kids?

At the moment, I have no idea! We should start by recognizing how often this fails — Gabriel Wyner writes about what he learned speaking with linguists who research this. Their finding: naive practice doesn’t work.

Happily, deliberate practice does — you need immediate feedback. So Wyner created a series of “minimal pair” flashcards to help you do this: pairs of words that sound exactly the same, save for one sound. In English, think bat/bit, cook/kook, and thigh/thy. You can download them for just $12 per language, but they’re a “legacy” product — he’s not providing support for them anymore, and as they require the program Anki to work, you need to be willing to get a little geeky. Frankly, his full Fluent Forever app include this, and you can get them for $10 a month, so that might make more sense.4

But this is all designed for motivated adults. How can we help kids learn this — and experience this as wonderful? I’ll write a bit more about this soon, but the worst case scenario, as I see it now, is you (the parent) will just need to use those tools to distinguish those sounds, and then guide your young kid through the same process.

Wyner, I believe, says that this stage should take 2–3 weeks, at 30 minutes of practice per day. I don’t know how long this is likely to take with kids.

I.I.: Can we Eganize the process of making the sounds?

I think so! Start by remembering that sounds are delightful. This is something we’ve covered in MAKING NOISE°, and something that came up when I was talking to Tom Harris, the linguistics PhD who writes the substack Thorn English and runs Thorn English Language Consulting, where he helps people perfect their English accents.5 I asked him what he’d recommend to help kids learn new languages, and his response couldn’t have been more Egan:

I am always frustrated by the (frankly understandable) reality that we teach vocab first, then learn how to structure that into some sort of syntactic sensibleness, and only then, if we get that far, learn how to speak naturally. The mechanics and psychology of sounds can be really hard to unlearn, so I would advocate an approach that encourages younger children to experiment with the speech sounds from a range of languages (it is actually really good fun — think about some of the click languages of Africa, ejective sounds and implosives, and the bilabial trill which is just a raspberry), and particularly with vowels to create a large inventory of available phonetic/phonological categories from an early age even if these don’t align with English.

To me, this looks a good deal like our pattern MAKING NOISE°, but I’m not sure yet how to focus that pattern on the specific sounds of your adopted language. If you’re interested in combining those, go for it, and tell us how it went in the comments!

Moving forward

That’s step 1 (help your kids taste “language”), step 2 (adopt a language as a family), and step three (tune your tongues). Next up is how to use Egan to build your vocabulary, and how to get into grammar. Look for those in a future post.

In the meantime, pepper me with questions and challenges!

Alessandro Gelmi, for new readers, is my partner-in-crime for a lot of Egan-related projects. He’s finishing a PhD in northern Italy and speaks… Alessandro, how many languages do you speak? Non-coincidentally, his master’s thesis was on using Egan’s paradigm to enrich classroom language teaching.

In order, those are Spanish, Russian, Mandarin, Arabic, Swahili, Turkish, Japanese, Finnish, and Nahuatl.

How many precisely? “43” is a common guess, which is irritatingly close to both the mystical number “42” and the easy-to-remember “44”, but is nobody’s favorite number. Per Tom Harris’s advice, I’ve edited this to say “meaningful sounds”: English makes more, but doesn’t distinguish between many of them. (See the light-L / dark-L situation for an example.)

If you’re considering his app, this video gives a good overview of what it includes, and how it works. (I’m putting this as a footnote, because frankly I’m worried that I’m going to come across as a shill for Fluent Forever! Dang it, its whole approach really rubs my belly the right way. Caveat emptor.)

I love languages, I had tried many times with various methods (books, apps, courses etc). Finding out about the Comprehensible Input method has gotten me so much further in acquiring another language than any other method. CI method is about acquiring another language rather than learning it. CI teachers use a lot of stories to teach the language. I have been using Dreaming Spanish to acquire Spanish.

It seems criminal that I haven't responded before but life kept intervening. Anyway, here goes.

I've been a second language teacher for about 15 years. My mental model is that some people are going to learn languages MUCH more easily than others. If you are in this lower-friction group, congratulations.

For those who tend to succeed, whether easily or with more effort, there are several common factors:

1) There needs to be something they want within the language. I have a bunch of students who became extremely fluent watching YouTube videos and even brainrot short form content. It motivated them.

It could be books or stories or video games. Immersion is a great reason to want to learn a language. That could be a trip. Ideally this isn't something they can simply translate or find in their own language.

For some kids the simple feeling of improvement is enough to motivate them to keep going- don't bank on this, it often is this way for easy language learners.

2) deliberate practice - often this means doing something outside of school. Tutorial lessons can work if the student wants to improve. Self study can work if there is place where students can 'test' their learning.

This is weightlifting, not a race for output. I think some of the apps are so frictionless that the information gained only stays in the app. The information should be pulled out into more realistic applications if you want it to generalize

3) there needs to be a safe environment students can test what they've learned and receive authentic feedback. This could be conversation. Reading or listening can be a test, too. Students who understand pass the test. The key point is that the language feedback that they receive is accurate and that they are willing to engage. This is environmental.

I cannot stress enough that learning a language is a vulnerable experience and learners need to feel that the benefits outweigh the fear and vulnerability. It is easier with younger children because they feel less social fear. The ability to experiment with language is crucial.